Chimney

Rock Park

Chimney

Rock Park  Chimney

Rock Park

Chimney

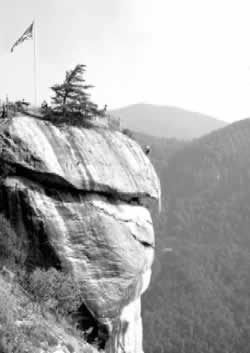

Rock Park [Fig. 25(4)] Chimney Rock—a private recreational facility owned and managed by the fourth generation of the family that originally developed the park—proudly bills itself as "the best of the mountains, in one place." In a region rich in natural treasures, that might seem to be pushing things a bit, yet Chimney Rock—with its unique geology, stunning long-range views, and abundant flora and fauna (including many rare species)—can legitimately make the claim.

The involvement of the Morse family fortunes with Chimney Rock can be traced back to 1900, when Lucius B. Morse, a physician from Chicago, paid $.25 to ride a mule to the top of the rock monolith looming over Hickory Nut Gorge. When he took in the 75-mile view from up above, it spawned a lifelong obsession.

Over the next several decades, Morse and his brothers (with the backing of investors) acquired thousands of acres of land, built neighboring Lake Lure, and gradually developed the park site, adding a road, a bridge, a three-story restaurant, and even the Cliff Dwellers Inn. The Great Depression seriously dented Morse's ambitious plans for a world-class resort in the gorge, but he hung onto his beloved rock, gradually adding facilities. One of the remarkable additions was the 258-foot elevator shaft bored and blasted through the rock from 1946 to 1948, which created almost instant access to the view from the top.

Predictably,

the park's image has also changed with the times. Originally a 1920s-style rustic

resort, it provided the backdrop for many early movies, including the Blue

Ridge Bandit series. Ironically, wild animals were shipped to Chimney Rock

for the filming. Through the lean Depression and postwar years, however, the

park became a seasonal attraction operating on a shoestring budget. The Chimney

Rock HillClimb, a nationally known sports-car event, ran annually for 40 years

until it was discontinued in 1995.

Predictably,

the park's image has also changed with the times. Originally a 1920s-style rustic

resort, it provided the backdrop for many early movies, including the Blue

Ridge Bandit series. Ironically, wild animals were shipped to Chimney Rock

for the filming. Through the lean Depression and postwar years, however, the

park became a seasonal attraction operating on a shoestring budget. The Chimney

Rock HillClimb, a nationally known sports-car event, ran annually for 40 years

until it was discontinued in 1995.

Today, the emphasis is firmly on ecotourism. A new Nature Center in the Meadows helps give visitors a better understanding of the park's uniqueness. Regular workshops, slide presentations, and guided walks highlight the park's many natural wonders. And a series of free brochures, available at the park entrance and the gift shop, helps visitors identify key features.

Naturally, the main attraction is the chimney itself, a 535-million-year-old pillar of igneous rock. At some point in the distant geologic past, a portion of the earth's molten interior congealed into a substantial mass of granite buried far below the surface. Over the ensuing quarter of a billion years, the intensive workings of temperature and pressure turned the granite into Henderson gneiss. As the earth's surface gradually eroded, the chimney and surrounding cliffs were exposed. Subsequent erosion has more clearly separated the chimney from the cliffs. Other notable view spots within the park include the crest of Hickory Nut Falls (2,450 feet) and Exclamation Point, the park's highest peak (2,480 feet), which offers a stunning window into the gorge below.

The spectacular Hickory Nut Falls is a dancing ribbon of spume and spray plunging 404 feet against the sheer cliff face. Visitors may recognize the falls and some of the surrounding scenery from the 1991 film The Last of the Mohicans.

The park's 1,000 acres embrace a wide range of habitats, in large part because of the roughly 1,700-foot elevation range. The varied influences of water also play a part; the moist microclimate created on the high cliffs near the falls is one example.

That diversity enables a staggering variety of plant species to find homes at Chimney Rock. Round-leaf serviceberry (Amelanchier sanguinea), deerhair bulrush (Scirpus cespitosus, var. callosus), and choke cherry (Prunus virginiana) all inhabit the cool, wet cliffs. Biltmore sedge (Carex biltmoreana), until recently believed to be extinct in North Carolina, can be seen along the upper trails, as can Carey's saxifrage (Saxifraga careyana). A host of other rare plant species are found within the park boundaries (but not always near the trails), including bleeding heart (Dicentra eximia), spreading rockcress, white-leaf sunflower, sweet pinesap (Monotropsis odorata), fringetree (Chionanthus virginicus), two species of mock orange (Philadelphus hirsutus and P. inodorus), shooting star (Dodecatheon meadia), lesser rattlesnake orchid (Goodyera repens, var. ophioides), white irisette (Sisyrinchium dichotomum), pale honeysuckle (Lonicera flava), and divided-leaf ragwort (Senecio millefolium). A detailed free brochure lists hundreds of plants found in the park and tells when they bloom and where to look for them.

Chimney Rock is also home to a number of giant trees, including a tulip tree, a red oak (Quercus rubra), and a cucumbertree (Magnolia acuminata) believed to be more than three centuries old. Before Morse purchased the park lands, there were no roads on the mountain, and the trees' inaccessibility probably saved these arboreal behemoths from the loggers. Other tree species in the park include the chestnut oak (Quercus prinus), royal paulownia (Paulownia tomentosa), black locust (Robinia pseudo-acacia), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), basswood (Tilia heterophylla), black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), tupelo (Nyssa aquatica), and sweet buckeye (Aesculus octandra).

With its varied elevations and habitats, Chimney Rock offers outstanding bird-watching opportunities spring through fall, with more limited opportunities in the winter months. More than 100 species have been recorded in the park, and about a third of the species are known to breed there. Along the Rocky Broad River, yellow warblers (Dendroica petechia), yellow-throated warblers, and belted kingfishers may be seen. Higher up, the deciduous forests shelter scarlet tanagers and more than a dozen species of warblers and vireos, including the elusive cerulean warbler and Swainson's warbler (Lymnothlypis swainsonii), in the summer. Cerulean warblers are known to breed in the park, thanks to the discovery of a nest several years ago (only the second ever found in North Carolina).

Because of their unusually cool microclimate, Chimney Rock's sheer cliffs attract several bird species that usually breed only at much higher elevations. Birds here include the dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis) and common raven. A breeding pair of peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) first nested in the park in 1990, successfully raising three chicks in the cliffs beyond Devil's Head that summer. More common birds of prey include black vultures (Coragyps atratus) and turkey vultures (Cathartes aura), both residents in the park.

Spring and fall, when many species migrate through Hickory Nut Gorge, are the prime times for birding at Chimney Rock. Flocks of tanagers, vireos, and warblers move through on their way north in spring and return on their way south in the fall. Fall is especially notable for the spectacular hawk migrations, when hundreds of broad-winged hawks (Buteo platypterus) and smaller numbers of sharp-shinned hawks, Cooper's hawks (Accipiter cooperii), and red-shouldered hawks (Buteo lineatus) can be seen. On a single, memorable day in 1992, more than 3,000 broad-winged hawks were observed flying south. Another fall delight is the annual migration of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus).

Look for squirrels and chipmunks scampering among the trees along park trails. Due to the large number of park visitors, other local wildlife, such as groundhogs, white-tailed deer, and the nocturnal raccoons and gray foxes, are not so easy to spot.

Several miles of nature trails enable visitors to immerse themselves in different park habitats. The Forest Stroll, an easy .75-mile walk along an old jeep trail, cuts through dense forest, highlighting interesting rock formations and notable plants en route to its terminus at the base of Hickory Nut Falls. The moderate-to-strenuous Skyline Trail hugs the cliffs up above, offering periodic breathtaking views on the way to the top of the falls. And, for other dedicated scramblers, the Cliff Trail provides an in-between route to the same destination, winding among the sheer, piled-up rocks. Between its flora and fauna, its unique geology, and its stunning views, Chimney Rock Park can keep the nature-loving visitor happily occupied for several hours or more.

Bottomless

Pools

Bottomless

Pools Set in the midst of a virgin forest within the beautiful Hickory Nut Gorge [Fig. 25(5)], the Bottomless Pools and waterfalls of Pool Creek have been a popular spot since they opened in 1916. The main attractions are the three separate pools each with its own waterfall and personality. Along the pathways to the pools, rhododendron, mountain laurel, and a variety of other evergreens form a thick understory over lush beds of wildflowers.

Unlike the watershed of the nearby Broad River, the 6-square-mile watershed of Pool Creek flowed slowly, which in turn carved the pools, or unusually large potholes, in the solid rock. As Pool Creek flows from its source higher in the mountains down to Lake Lure, it runs over many fractures, or joints, as geologists refer to them, in the underlying Henderson granite gneiss. Two sets of fractures are prominent in many places along the course of the stream. The flowing water can more easily erode along these fractures than on massive unjointed rock.

Not only is the weakness of the rock emphasized at the intersection of two fractures, but the course of the water is altered into a swirling motion. Pebbles and stones carried into the whirlpool intensify the erosion process, carving steep, circular walls as they cut deeper into the rock below.

Scientists do not agree on how long this process has been going on at the pools. Some say only 25,000 years while other contend 100,000 years. What they do agree on, after studying the surrounding rock and other factors, is that the pools are younger than a few hundred thousand years old.

Lake Lure, the 1,500-acre lake described by National Geographic as one of the most beautiful man-made lakes in the world, formed when a dam 115 feet high and more than 600 feet long was built across the Rocky Broad River. As deep as 100 feet in places, Lake Lure features a 27-mile shoreline with many small bays and inlets. Bass and trout fishing and all kinds of water sports are enjoyed in the lake and along its shores under the supervision of resident mallard ducks and great blue herons.

Nearby, the towns of Lake Lure and Chimney Rock offer a selection of bed and breakfast inns and restaurants that serve local trout, barbecue, and other dishes indigenous to the area. The town of Chimney Rock has been undergoing major changes, adapting to the changing interests of visitors, especially those attracted to the natural beauty of nearby Chimney Rock Park (see Chimney Rock Park). Lake Lure Inn, taking its name from the lake it overlooks, offers fine dining and accommodations.

Caution: Rocks in the creek bed are slippery, and visitors are encouraged to stay on the trails and to watch children closely.