Grandfather

Mountain

Grandfather

Mountain  Grandfather

Mountain

Grandfather

Mountain [Fig. 12] Looming rough and ornery from the Blue Ridge Parkway, Grandfather Mountain is a 4,000-acre reserve teeming with natural diversity. So much so, in fact, that in 1994 the United Nations designated the 4,000-acre park as a member of the international network of Biosphere Reserves. To meet strict biosphere criteria, Grandfather Mountain had to prove that it had global ecological significance, legal protection from development, a history of scientific study, and provisions for public education. Grandfather Mountain is the first privately owned biosphere out of 337 units in 85 countries.

More than a century ago naturalist Elisha Mitchell noted that the rocks here were unusual for the eastern Blue Ridge. Grandfather Mountain is at the heart of a geologic paradise known appropriately as the Grandfather Mountain Window, a region covering more than 800 square miles in northwestern North Carolina. Millions of years ago when these mountains were formed by the collision of two continental crusts, huge sheets of rock were pushed over each other. The Blue Ridge Thrust Sheet moved more than 60 miles to cover what is now Grandfather Mountain. Some scientists believe these mountains were once 10 times as high as they are today, but erosion over hundreds of millions of years has opened a "window" where younger rock shows through. This window, surrounded by mostly older rock, permits the study of a sequence of rocks ranging in age from old to young. Grand-father Mountain also holds the distinction over other southern mountain terrains as the most extensively bouldered.

Sixteen distinct habitat types can be found on Grandfather Mountain. Each supports a different balance of life, and together they support one of the most diverse groups of flora and fauna in the Southeast. In addition to a range of fir, spruce, and oak forests, Grandfather hosts the rich cove forest, acidic cove forest, and Canada hemlock forest. The montane calcareous cliff habitat features cliff communities with an open canopy and bare substrate resulting from its steepness and rockiness. The heath-bald habitat is distinguished by the absence or near absence of trees; any trees found here are stunted and not much taller than shrubs. The spray-cliff habitat has vertical to gently sloping rock faces, constantly wet from the spray of waterfalls, and the high- elevation rocky summit has substantial areas of bare rock.

The

short drive from the preserve's entrance to the top passes through as many climate

zones as a drive from North Carolina to Newfoundland, including temperature

changes from 5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Halfway up the mountain lies a complex

of natural wonders such as Split Rock and Linville Bluffs and man-made wonders

such as the seven wildlife habitats, the Visitor Center [Fig.

12(7)], and Nature Museum [Fig.

12(8)]. The habitats are home to more common species such as black bears,

white-tailed deer, otters, and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), as

well as fauna such as panthers (Felis concolor) and bald eagles (Haliaeetus

leucocephala) that are now rare to the area. Together, however, these habitats

provide a sense of the wildlife that roamed here 200 years ago when the Cherokee

called the mountain Tanawha, or "Great Hawk." In keeping with

its name, the mountain is populated with hawks and owls, including endangered

species such as the northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadicus) and peregrine

falcon. Grandfather Mountain is also a central rallying point for approximately

50 ravens, possibly the largest colony east of the Rockies and south of New

England.

The

short drive from the preserve's entrance to the top passes through as many climate

zones as a drive from North Carolina to Newfoundland, including temperature

changes from 5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Halfway up the mountain lies a complex

of natural wonders such as Split Rock and Linville Bluffs and man-made wonders

such as the seven wildlife habitats, the Visitor Center [Fig.

12(7)], and Nature Museum [Fig.

12(8)]. The habitats are home to more common species such as black bears,

white-tailed deer, otters, and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), as

well as fauna such as panthers (Felis concolor) and bald eagles (Haliaeetus

leucocephala) that are now rare to the area. Together, however, these habitats

provide a sense of the wildlife that roamed here 200 years ago when the Cherokee

called the mountain Tanawha, or "Great Hawk." In keeping with

its name, the mountain is populated with hawks and owls, including endangered

species such as the northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadicus) and peregrine

falcon. Grandfather Mountain is also a central rallying point for approximately

50 ravens, possibly the largest colony east of the Rockies and south of New

England.

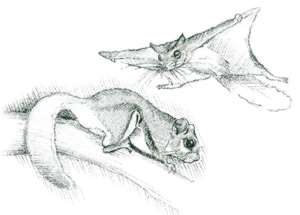

A contemporary, 11,000-square-foot Nature Museum hosts an auditorium presenting award-winning nature films and sophisticated weather stations open to the public, as well as the Nature Museum itself. The museum houses two dozen remarkably realistic displays of wildflowers, edible berries, mushrooms, minerals, birds, and some of the endangered species living in the biosphere. Grandfather hosts 11 globally imperiled species (species found in 20 or fewer places worldwide) such as the North Carolina Funnelweb tarantula, rock gnome lichen, bent avens, Blue Ridge goldenrod, spreading avens, Heller's blazing star, mountain bittercress, trailing wolfsbane (Axonitum reclinatum), Gray's lily (Lilium grayi), Carolina saxifrage, and manhart's sedge. A total of 42 rare and endangered species have been identified on the mountain (more than in all of the Great Smoky Mountain National Park), including North Carolina critically imperiled species (five or fewer occurrences) such as Virginia big-eared bat (Plecotus townsendii virginianus), Carolina northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus coloatus), magnolia warbler (Dendroica magnolia), mountain bluet, rosefoot, and hemlock parsley. Grandfather Mountain is also distinguished as one of the Blue Ridge's best sites for salamanders with up to 16 species. The Yonahlossee salamander (Plethodon yonahlossee), for example, is unique to a small area leading to the edges of Virginia and Tennessee with Grandfather Mountain at the center. Such a diverse and lush ecosystem helps explain Grandfather's longtime attractiveness to naturalists and botanists. Asa Gray, André and François Michaux, Elisha Mitchell, and more recently John Muir have all rejoiced in the native bounty they found here (see Naturalists).

As the road winds toward the top, several points along the way are worth a stop, including the panoramic Cliffside Picnic Area and Scheer Bluff overlooking red spruce–hardwood forests to the mountains beyond. Almost 2 miles from the top, the Black Rock Parking Area offers a seemingly endless mountain vista, as well as the entrance to Black Rock Nature Trail and Bridge Trail.

Black Rock Nature Trail [Fig. 12(4)] is a 1.8-mile-long, easy-to-moderate walk through northern hardwood and spruce forests at elevations ranging from 4,700 feet to 5,040 feet. In spring and summer, bird watchers flock here to spot red-breasted nuthatches, winter wrens (Troglodytes troglodytes), and chestnut-sided warblers. Near the well-marked trailhead, interpretive pamphlets, stored in a box, are packed with interesting facts about the 35 stops along the trail. The American mountain-ash, yellow birch (Betula lutea), and sweet pepperbush (Clethra acuminata) are cited, as well as the nutritious and medicinal smooth rock tripe (Umbilicaria mammulata) growing along the Arch Rock.

At

the Moss Garden, quartz veins, formed when still-molten quartz filled cracks

between faster-cooling rock, are studied, and the role of small plants and mosses

in soil formations is explored. Sand myrtle (Leiophyllum buxifolium prostatum)

helps explain Grandfather Mountain's nickname, "An Island of the North

in the South." This low-growing evergreen shrub, which thrives on the mountain's

exposed rocky outcrops, is not usually found this far south. Many species found

only in New England or Canada grow in the upper elevations of the Blue Ridge,

remnants of early ice ages when cold-climate species grew throughout the Southeast.

As temperatures warmed, the flora and fauna moved to these higher elevations

to survive, and many remain there today. Finally, the trail leads to a spectacular

view of Table Rock, Hawksbill Mountain, Linville Gorge, and Mount Mitchell,

among others, before turning to retrace the path back to the parking lot.

At

the Moss Garden, quartz veins, formed when still-molten quartz filled cracks

between faster-cooling rock, are studied, and the role of small plants and mosses

in soil formations is explored. Sand myrtle (Leiophyllum buxifolium prostatum)

helps explain Grandfather Mountain's nickname, "An Island of the North

in the South." This low-growing evergreen shrub, which thrives on the mountain's

exposed rocky outcrops, is not usually found this far south. Many species found

only in New England or Canada grow in the upper elevations of the Blue Ridge,

remnants of early ice ages when cold-climate species grew throughout the Southeast.

As temperatures warmed, the flora and fauna moved to these higher elevations

to survive, and many remain there today. Finally, the trail leads to a spectacular

view of Table Rock, Hawksbill Mountain, Linville Gorge, and Mount Mitchell,

among others, before turning to retrace the path back to the parking lot.

The Bridge Trail is a moderate, .4-mile, switchback trail that leads to the famed Mile High Swinging Bridge, built in 1952 to span an 80-foot-deep ravine. It is reportedly the highest suspension footbridge in America. The route travels through massive rock formations that help form Grandfather's craggy Linville Peak and a cross-section of trees, shrubs, and wildflowers including examples of Azaleea vaseyi, a rare and endangered May-blooming shrub; Grandfather Mountain has the largest population of vaseyi in the world.

Some of the South's finest alpine hiking trails traverse Grandfather Mountain. When French explorer-botanist André Michaux arrived at the summit of Grandfather Mountain during the eighteenth century, he broke into song, certain he had reached the highest point in America. Although at 5,964 feet the mountain falls short of that distinction, it is still a spectacular sight. The 12-mile trail system is documented in the free Backcountry Trail Guide available with admission tickets or hiking permits. Within the nine-trail system, Grandfather Trail [Fig. 12(5)] is the most spectacular. It starts near the Swinging Bridge and eventually connects to Grandfather's three highest peaks. Its length of only 2.2 miles is deceiving—Grandfather Trail is rugged and difficult to navigate (requiring wooden ladders in places to traverse sheer cliff faces). It intersects with the Daniel Boone Scout [Fig. 12(2)] and Cragway trails, which in turn lead to the Tanawha Trail and the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Profile Trail [Fig. 12(3)], with a trailhead off Highway 105 near Banner Elk, offers a gradual ascent with numerous switchbacks to ease the climb up the mountain face along its 2.7-mile trek (one-way). Like all the trails on Grandfather Mountain, it eventually connects with the other trails. Along the way, Profile Trail passes through more ecological communities and climate zones than any other trail on the mountain.

Permits or admission tickets are required for hiking all trails (strictly enforced). All hikers should obtain a Backcountry Trail Guide when purchasing permits/tickets. Trails are carefully mapped and illustrated with information on length, degree of difficulty, and blaze color.

The dramatic geology has produced a number of waterfalls in the area. Streams on Grandfather's northern side feed into the Watauga River before they develop enough size to create waterfalls. Streams on the southern side, however, are able to build in size before tumbling down the Blue Ridge escarpment, which from the summit of Calloway Peak to the valley below is a drop of 5,000 feet, the greatest drainage relief found along the escarpment. In his book North Carolina Waterfalls, Kevin Adams offers detailed information on locating nine nearby waterfalls.