The Natural Georgia Series: The Flint River

|

The Natural Georgia Series: The Flint River |

|

Thanksgiving

Day, 1987. Unlike most people in southwest Georgia who are sitting down to turkey

dinners and football games, Paul DeLoach is exploring an underwater cave in

north Florida. It is truly a day of thanks for DeLoach. First, he is

exploring a section of the Wakulla Springs cave system that no man has ever

seen. Secondly, he and his partner will survive a series of accidents that could

have easily resulted in two dead cave divers.

Thanksgiving

Day, 1987. Unlike most people in southwest Georgia who are sitting down to turkey

dinners and football games, Paul DeLoach is exploring an underwater cave in

north Florida. It is truly a day of thanks for DeLoach. First, he is

exploring a section of the Wakulla Springs cave system that no man has ever

seen. Secondly, he and his partner will survive a series of accidents that could

have easily resulted in two dead cave divers.

A couple of things have gone wrong. DeLoach and his partner, Sheck Exley, have used propulsion scooters to travel quickly to this unexplored section of the cave. But Exley's scooter breaks down, leaving him with a longer swim out-and causing him to use more air-than they anticipated. Fortunately, the divers have a contingency plan, one of many back-up measures they've developed in more than 15 years of diving together.

DeLoach tows Exley ahead to a place where they've stashed emergency air tanks. From here, Exley will strap on three more tanks and slowly swim out the rest of the way. DeLoach will motor out on his scooter.

Within minutes, however, DeLoach is unable to catch a full breath of air. Not only has he over-exerted himself by towing Exley, but too much oxygen in his diving gas has led to oxygen toxicity. Soon he experiences irregular breathing. His eyes and nose start twitching. When he switches to his safety tank, the symptoms of oxygen poisoning grow worse. He starts to slip in and out of consciousness.

Despite all this, DeLoach keeps his grip on the scooter and motors up to 190 feet below the surface. He stays calm, focused. Over the years, he's recovered the bodies of too many divers who drowned while trying to "push the bubble." (Just like test pilots who flew experimental aircraft in the 1960s talked about "pushing the corner of the envelope," underwater divers talk about pushing the last bubble of air.) Finally, after moving up to 175 feet, he returns to a normal breathing rate because he is slightly closer to the surface.

At this stage, when DeLoach can safely continue his slow ascent, he doesn't. Instead, he motors back down into the cave to check on what's keeping Exley. He is relieved to find his partner safe and sound, but moving slowly because of the extra tanks. Later, in the underwater decompression chamber that lies suspended in Wakulla's main cavern, the two men talk about what went wrong. As a result of their misadventure, they draw up new safety protocols for the other divers on their team.

Almost

15 years later, DeLoach mentions that Thanksgiving Day experience to stress

the importance of contingency planning-not only in diving, but in protecting

natural resources. His lesson is simple, and he speaks with a quiet intensity

that carries a great heft. After all, few of us really understand the meaning

of trust like someone facing a major breakdown in 200 to 300 feet of water.

Few of us can fully appreciate the importance of strategic planning unless we've

been in an environment that is absolutely unforgiving of error.

Almost

15 years later, DeLoach mentions that Thanksgiving Day experience to stress

the importance of contingency planning-not only in diving, but in protecting

natural resources. His lesson is simple, and he speaks with a quiet intensity

that carries a great heft. After all, few of us really understand the meaning

of trust like someone facing a major breakdown in 200 to 300 feet of water.

Few of us can fully appreciate the importance of strategic planning unless we've

been in an environment that is absolutely unforgiving of error.

As Bob Kerr, chief negotiator for the state of Georgia in the tri-state water wars, says: "When Paul DeLoach talks, people in his part of the world listen."

More people are hearing DeLoach's voice these days as a result of his leadership on the Southwest Georgia Water Resources Task Force. This four-year-old regional association, which holds "summits" on various water issues, is earning high praise from researchers, political leaders, and conservation groups around the state.

Lindsay Boring, director of the Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, credits the Task Force for putting information on the table instead of partisan positions.

"The reality is that there's precious little known about our water crisis in this part of the state," says Boring. "They've been leaders in the state of Georgia in establishing a very active educational program so that people understand what the magnitude of the challenges are."

Lonice Barrett, commissioner of Georgia's Department of Natural Resources, also points out their leadership role.

"Since day one this particular group has worked not from an adversarial standpoint but from a very strong willingness to talk and listen and provide input. That's what is unique about this group."

One reason the Task Force has been so effective, according to Georgia's Lieutenant Governor Mark Taylor, is Paul DeLoach.

"His leadership was the key to setting southwest Georgia water needs above some other water issues in Georgia," says Taylor, pointing to the $10 million that the General Assembly set aside in 2000 for the Flint River drought protection program.

Jerry McCollum, Georgia Wildlife Federation president, believes that DeLoach has set the tone for the Task Force. "When you talk to him," says McCollum, "He doesn't put himself or his industry first. With him, it's water conservation."

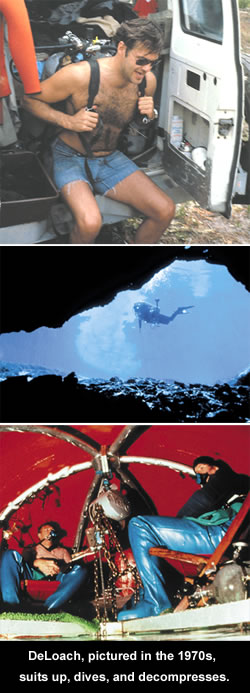

DeLoach first discovered the beauty and challenge of underwater cave diving while majoring in business at the University of Georgia. As a minister's son growing up in North Carolina, DeLoach says he preferred swimming, snorkeling, and fishing over team sports like football. His hero was Jacques Cousteau, the French explorer who wrote books and starred in documentaries about the underwater world. By the time DeLoach ventured into his first underwater cave in the late 1960s, he was already an experienced spelunker and open-water scuba diver. Putting the two together was a natural step for someone curious about how things connect.

Of course, what made the exploration more challenging-and dangerous-was that nobody knew much about underwater cave diving at the time. Few maps of caves existed and the equipment was makeshift, such as the water-filled bleach jugs they used in the days before buoyancy compensators. Once underwater, divers could fill the jugs with air from their regulator exhaust and use them, somewhat awkwardly, for ballast.

As DeLoach and his friends explored farther into north Florida caves, setting world records in the process, they became the pioneers of a new sport. It fell to them to test the new equipment, map the caves, and reel out the safety line that would guide them back to the cave entrance. Basically, they defined the rules for survival in an outdoor activity that, in 1974 alone, claimed 26 lives in Florida.

In later years, DeLoach's close friend Sheck Exley would be called the "father of American cave diving" for his voluminous writings and relentless pursuit of new world records. In 1994, Exley died while attempting to push the bubble and set a new 1,000-foot depth record in a Mexican cave.

"Paul made a really good partner for Sheck," says Daniel Lenihan, one of the world's leading underwater archeologists and author of a recently published book that includes a few of DeLoach and Exley's adventures. He describes DeLoach as "one of the more quiet leaders at the frontier of cave diving." While Exley set one world record after another, often it was DeLoach who planned for every contingency and provided vital behind-the-scenes support.

"Paul had equal capabilities and talents, but he was the steady hand, the moderating influence. He would push limits, but he was very methodical and very smart about it. He would look at everything from about 10 different angles before doing it."

Contrary to most people's beliefs, cave diving does not involve a lot of squeezing through tight crevices, or inching your body through long, silty passages. There is some of that, but most underwater limestone caves in south Georgia and north Florida are relatively roomy-some, like Wakulla, are even palatial-and filled with crystal-clear water. When the divers illuminate the caverns with their quartz-halogen lights, the effect is akin to space travel, of floating weightless through an exquisite rock garden.

As with any golden age of exploration, the first underwater cave divers discovered amazing sights. In the early 1970s, DeLoach and his friends explored a Mexican spring that had once been used by the Aztecs as a ceremonial dumping pit. On rocky ledges they saw broken pots, figurines, and pipes. Everything the men saw, they left untouched. It's a creed DeLoach still lives by today. Although he is often called on by researchers to bring up rare cave specimens (albino crawfish, albino catfish, blind cave salamanders, and amphipods), he will only do so if researchers have first obtained necessary permits.

One of the highpoints of DeLoach's diving career was the 1987 Wakulla Project. After receiving backing from the prestigious and highly selective Explorers Club (which supported Sir Edmund Hillary's conquest of Mount Everest) and National Geographic Society, an elite group of underwater cave divers set out to explore one of the world's "crown jewels" of springs, Wakulla Springs near Tallahassee, Florida. In recognition of his strategic planning abilities, DeLoach was named project coordinator.

The team mapped a total of 2.3 miles of underwater tunnels, while exploring caverns in average depths of 260 to 320 feet. For the first time ever, a human being stayed underwater for 24 hours without any means of life support except a backpack-sized rebreather (developed by project leader Bill Stone). Thanks to extraordinary planning, team members reached out to touch a new frontier, and all returned home safely.

Today, if you ask DeLoach if he's ever felt afraid once he's inside an underwater cave, he takes a moment to answer. He seems contemplative by nature, but he's also someone who has spent long hours suspended underwater with only his thoughts for company. Non-divers often fail to consider how much time passes during the decompression stages of a deep dive. For example, if DeLoach dives down to 150 feet and explores for 60 minutes, he will spend another 90 minutes or more underwater as he slowly, carefully, rises to the surface. If he isn't methodical about this decompression period, in which his body gradually rids itself of excess nitrogen, he'll risk being crippled by the bends.

The wear and tear of deep-water diving-especially the effects of nitrogen build-up in the body-has possibly contributed to a decrease in hearing in one of DeLoach's ears. This time spent communing in the earth's watery womb has also turned him into something of a New Age thinker. Or, in the words that he chooses to describe a long-time friend, "an old soul."

When he finally replies, "I am properly motivated by fear in an environment that is very unforgiving of any kind of recklessness, disregard, or disrespect," he undercuts the seriousness of his words with a mischievous grin. Then he adds, "If you know that going in, you learn to take precautions."

In

1984, during the early days of planning the Wakulla Project, DeLoach left his

job with the Boys Club of America to become Miller Brewing Company's community

affairs manager in Albany. He had worked with the Boys Club since his graduate

school days in Athens, gradually assuming the duties of fundraiser for capital

building projects. For years he traveled across the southeastern U.S. while

participating in a variety of money-raising campaigns. In Albany, he would finally

be able to settle down closer to friends and his beloved underwater caves. He

would also be employed by a brewery that would become as passionate about conservation

issues as DeLoach himself.

In

1984, during the early days of planning the Wakulla Project, DeLoach left his

job with the Boys Club of America to become Miller Brewing Company's community

affairs manager in Albany. He had worked with the Boys Club since his graduate

school days in Athens, gradually assuming the duties of fundraiser for capital

building projects. For years he traveled across the southeastern U.S. while

participating in a variety of money-raising campaigns. In Albany, he would finally

be able to settle down closer to friends and his beloved underwater caves. He

would also be employed by a brewery that would become as passionate about conservation

issues as DeLoach himself.

Among industries in southwest Georgia, Miller is a medium-sized user of water. The brewery draws 3 million gallons of water per day from the deeper aquifers. One million gallons is consumed each day as the water begins its more than 20-day-long transformation into a golden-hued, alcoholic beverage. The other 2 million gallons of water are used (and re-used) to produce steam and, most importantly, to keep vessels and surfaces sparkling clean and free of bacteria that might cause spoilage.

Motorists who drive by the Miller brewing plant on GA 300 can catch a glimpse of the famous red and white Miller label atop a silo-like building in the distance. But that's about all they can see. The plant itself, built on a runway of the former Turner Air Force Base, sits in the middle of 1,700 acres, most of which are managed for pine trees. When Miller acquired as much land as it did, however, it wasn't solely for the reason of managing a timber business. The company wanted access to the water located below the ground.

Albany has always depended on the abundance of its water supply to attract manufacturers like Miller, Procter & Gamble, Merck, and Cooper Tire. In 1978, when the brewery had its groundbreaking ceremonies, most people in the region thought the supply was endless. Morgan Murphy, a retired chairman and CEO of an Albany bank, recalls the feeling: "With our aquifers and our rivers and streams, we thought we just had all the water in the world. In fact, we used to advertise ourselves through our chamber of commerce, 'Come down here, we've got all the water you need.'"

Miller, along with the other industries and municipalities who can afford to drill deep, bypasses the two easy-to-reach aquifers. The first is a surface aquifer that fluctuates rapidly with rain and drought, and contains relatively low-quality water. The second is the popular Upper Floridan aquifer, which many homeowners, municipalities, industries, and farmers rely on for their drinking water. One of the most productive aquifers in the world, the top of the Floridan goes from average depths of 30 to 100 feet, and is relatively easy to reach. It underlies about 100,000 square miles in Florida and the southernmost regions of Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina.

Instead, the brewery draws its high-quality water from deeper aquifers, the Tallahatta Formation of the Claiborne aquifer and the Clayton, located in the 500-foot-plus range (farther down is the Providence aquifer, but it mostly consists of sand and doesn't provide a high yield of water). The water here is nicely filtered and doesn't need much treatment except for some chlorination.

David Dixon, the environmental compliance administrator at Miller Brewing, says, "Even though we would like to say, 'If you're on top of the water, it's your water,' we understand that what's your water today is flowing downhill to somebody else tomorrow or the next month."

Dixon says that DeLoach influences the principles and policies of water use at the plant. He also helped convince the brewery management team to conserve water.

"Miller Brewing is looked upon, as other industries are, as a big consumer and user of water," says DeLoach. "With water being such a precious commodity in the region, why not be on the front end of these issues?"

In the last three years, the brewery reduced water use by 18 percent, lowering its water consumption to make 1 barrel of beer from 4.85 barrels of water to 3.99 barrels. Considering that the brewery produces over 8 million barrels of beer each year, that's a savings of over 6 million barrels (over 200 million gallons of water). Miller now uses gray water in processes that don't need fresh water. It has also cut back water use in its grounds area, and implemented a leak detection and repair program that saves gallons.

Dixon proudly says that Miller has never had a water quality violation and has never even been close in its 22 years of operations. Last year, the Georgia Water Pollution Control Association recognized Miller's achievements, naming it the Industrial Plant Wastewater Treatment Plant of the Year.

The capacity of Miller's onsite wastewater treatment plant is about 6.5 million gallons a day of treated waste, but the plant treats less than 2 million gallons on a normal day. Aerobic processes in the treatment plant break down the residual beer and leftover cleaning compounds in the water. The resulting materials-carbon ions, sodium, magnesium, nitrates, and other things-are removed and transformed into fertilizer for Miller's resident hay crops and pine forest. The water that is finally discharged into the Flint River (from an underwater pipeline just below the Georgia Power dam) is cleaner than the water flowing in the river.

As passionate as DeLoach is about Miller's conservation techniques, he's equally passionate about this river that the Native Americans once named after the hard, fine-grained quartz found on its banks.

On a recent December morning, DeLoach wants to show off the Flint to a visitor. Because the conditions aren't right for a river cruise, he opts for a driving tour, which includes seeing a few places that reveal some of the unique features of the Dougherty Plain. Over the course of the morning, it becomes obvious that DeLoach has a deep, abiding respect for the people and places of southwest Georgia.

As Lonice Barrett says, "Every time I see or hear of anything that's happening in southwest Georgia, Paul DeLoach is somehow or another involved."

Barrett lists DeLoach's involvement in starting the state's nongame wildlife program, and Miller Brewing's contributions to the Hunters for the Hungry program, the Fall Feather Hunt (an economic development initiative of the Georgia Chamber of Commerce), and the Easter Seals bass tournament. All told, Miller Brewing and its parent company, Philip Morris Companies, declare their social responsibility to the community by donating $600,000 to $700,000 to Georgian charities on an annual basis.

As Miller's representative, there's a place at the table wherever DeLoach

goes. His leadership on the Southwest Georgia Water Resources Task Force ("terribly

more time-consuming that I ever thought about") led to his appointment as a

member of the statewide Drought Planning Committee. On a local level, he chairs

a policy-making board at Albany Technical College and co-chairs the Martin Luther

King Celebration Day in Albany, which helps raise money for the Albany Civil

Rights Museum. He is a past president of the Albany Area Arts Council. DeLoach

is also active in Miller's "Tools for Success" program, which works with community

colleges and technical institutes to equip graduates with actual tools for their

chosen  professions.

professions.

When he's not making himself comfortable at a conference table, DeLoach kicks back on his 52-acre farm in Sumter County. These days he's interested in other activities besides diving (that wasn't always the case)-from bicycling to field trials. He also has a daughter in Athens who recently presented him with his first grandchild.

Today's sightseeing tour begins only a few minutes away from a busy Albany commercial strip. On a wooded, undeveloped piece of property located across the street from a low-income residential neighborhood, DeLoach leads the way through underbrush and low-hanging limbs.

It's an interesting juxtaposition. On a weekday morning when most people are headed to the office, this 55-year-old business executive, tall and rather striking in a black leather jacket (with "Miller" embroidered on the chest), is eagerly slipping through bushes and stepping over roots like a kid playing hooky from school.

Moments later he stands over a small, clear stream flowing through open moss-covered limestone walls. The water emerges from a spring farther up, then re-enters the ground via a siphon that he points out. If you came across a setting like this in a national park, minus the rusted-out junked car and scattered trash, you'd consider yourself lucky.

"People think of these low-lying areas as not having much value," says DeLoach. "But these are discharge and recharge areas for your drinking water. We need to help educate people as to where recharge areas are-their sensitivity and their impact. Most people don't understand that a wetland is the most perfect water cleaning and filtration system in the world."

DeLoach is convinced that education is the key to protecting water resources. He believes that once people know better, they will do the right thing.

That's why he is so excited about a RiverCenter that is being planned for downtown Albany. The project, which will join a hotel and conference center complex built along the banks of the Flint River, is part of an effort to educate the public, as well as revitalize the area. DeLoach hopes the RiverCenter will make a difference in everyone's awareness about local water resources.

"I'm real big on making sure we have some pretty accurate models that depict the hydrology and geology of the area so people can understand the connection," he says. "If we do a good job on that, we'll help people understand what policy makers have to think about."

A prominent feature of the RiverCenter will be a real-life bluehole spring built next to the building. Hopefully, in a few years, students and teachers will be able to see water flowing out of the Upper Floridan aquifer. They'll also see videos of underwater caverns, courtesy of you know who.

DeLoach envisions the center being the hub of the wheel that will encourage people to visit the spokes in the region-the wetlands, river, ponds, springs, and siphons.

He wants children to snorkel alongside 30-pound striped bass. "I guarantee you that once I get a kid's attention focused on those stripers, thinking he might want to catch some one day, and the relationship with that thermal refuge and wastewater and drinking water-if I make all those connections for a 10-year-old kid, guess what? I've got a 10-year-old environmentalist."

Thomas C. Chatmon Jr., President and CEO of Albany Tomorrow and the Flint RiverCenter project, speaks enthusiastically about DeLoach being on the team. "Some people are talkers, some are doers," he says. "Paul is a doer. He's actually going to do more than his fair share."

The next stop on DeLoach's sightseeing tour is another spoke in the region's

water wheel. He stands

behind a little apartment complex that overlooks Kinchafoonee Creek, one of

many tributaries that flow into the Flint. In the best of times, these creeks

nourish the river with fresh supplies of water. In the worst of times, developers

remove natural forest buffers from the creek banks so that apartment dwellers

can have a nice waterfront view. Unfortunately, that's the case here. DeLoach

points out the dark silt that covers the creek bed after a recent rain. Gradually,

this silt accumulates in the Flint River, makes its way down to the Apalachicola

River, where it threatens the health of Apalachicola Bay.

This

connection between a Georgia creek and a distant Florida bay is exactly the

kind of connection that DeLoach hopes the RiverCenter will make.

This

connection between a Georgia creek and a distant Florida bay is exactly the

kind of connection that DeLoach hopes the RiverCenter will make.

"You'd like to think people in the future would give up the great view of the river," DeLoach says. "Instead, the river would have all the natural buffers, and people could feel glad that they did the right thing."

The next two stops overlook the banks of the Flint River. DeLoach points out the locations of three springs where the aquifer meets the river. Normally, the springs replenish the river, but during floods the opposite is true. During the 1994 deluge, the Flint River forced water down into the aquifer, contaminating underground wells that were located as far as a mile away.

Of course, when most people in Albany think of springs, they only think of one: Radium Springs, Georgia's largest natural spring, with a normal discharge of 70,000 gallons of water a minute. For the last century, the commercially developed spring has drawn local residents to swim and relax in its sky-blue, bone-chilling, 69-degree water. In the 1920s, an ornate building was built overlooking the spring. Elaborate terraces and stonework were added to create the effect of a grand European resort. Unfortunately for developers, the stock market crash of 1929 prevented Radium Springs from becoming a tourist mecca outside the region, and what man so carefully wrought in the 1920s was finished off by two floods in the 1990s. Despite efforts to resurrect the cultural site by a preservation board (not surprisingly, DeLoach was a charter member), the spring has been purchased by the state of Georgia to protect water quality, as well as to serve as green space, habitat for striped bass spawning, and an educational resource.

DeLoach has a long acquaintance with the famous blue hole. He was one of the first divers to map the 1,532-foot-long Radium Springs cave system, as well as other caves in the area, including Chameleon Cave (3,585 feet) and Baker County's Blue Springs Cave (1,380 feet).

As Lieutenant Governor Mark Taylor says, "Stories about Paul diving in Radium Springs and the Flint are part of the lore of southwest Georgia. He's been a real leader in letting the public know what a phenomenal resource they are and how they need to be protected."

And at least twice in the last 30 years, DeLoach has stepped in to save the springs from irreparable harm.

In 1973 he and Exley made their first dive in Radium Springs at the request of the owner, who dreamed of turning the place into another Weekie Wachee. The owner planned to dynamite the spring and build a thick glass wall so that restaurant customers could munch frog legs while watching underwater acrobats. After DeLoach "made him very aware" that dynamiting the cave wasn't such a great idea-not only would he probably lose the cave and spring, he'd probably be cited eventually by the state for defaming and ruining a natural resource-and after "begging him not to do it," the owner changed his mind.

Early in 2001, the springs faced a more typical challenge when a developer wanted to build a 170-unit apartment complex across the road. DeLoach heard about the plan after the Albany Dougherty Planners had already recommended approval of the zoning request.

At the public hearing, DeLoach brought out his map of the Radium Springs cave system and, using an overhead projector, overlaid it on a map showing the proposed complex. Then he quietly pointed out how the apartments would be built on top of one of Georgia's largest underwater caves.

Next he calculated the amount of water falling over the complex and parking lot in a typical 3- to 4-inch summer downpour, which comes to about 7 million gallons of water. Then he pointed out the 1-million-gallon holding pond that the developer had proposed. "Where does the rest of the water go?" he asked. Over the road and into the sky-blue spring.

Afterwards, county officials decided to nix the apartment proposal.

"Paul recognized the threat to the caverns and was a tremendous friend of Radium Springs and the community in making recommendations about what he saw as the wise and prudent thing to do," says Boring, who lives in the Radium Springs community. "Everybody in the community is extremely indebted to him."

Today, DeLoach wants to show his guest the site of the proposed apartments. But while pointing out a partially filled sinkhole that was once a naturally occurring drainage point for the cave system, he's interrupted by a yellow jacket that flies out and lands three sharp jabs on his earlobe. He retreats with a few choice words. Then, rubbing his ear, catches his breath before resuming today's lesson.

Ideally, this low-lying residential area would be off-limits to save an important groundwater resource from the effects of run-off fertilizers, pesticides, and automobile wastes. In the future, he's optimistic that developers and city planners will know better-even if it took a public hearing to remind them earlier in 2001.

Leaving Albany behind, frequently rubbing his swollen earlobe, DeLoach points out the huge plantations that line the highway during the 20-mile drive south towards Newton. (There are over 40 plantations in this "Plantation Trace" region, most of them serving as exclusive hunting preserves that attract quail hunters from all over the world.) DeLoach very much appreciates the contributions these vast undisturbed areas make to the underground plumbing system of the region.

"If the plantations weren't here, we'd have subdivisions. Or we'd have other kinds of construction up and down the river. I can take you from Albany to Newton and there's not but two or three houses on the right-hand bank and probably 15 or 20 on the left-hand bank. I can take you from Newton to Bainbridge and there's again a half-dozen houses on the left and right banks."

Before the tour is over, DeLoach will check out another tributary of the Flint, a healthy little creek where you can find mussels and prehistoric sand dollars. The final stop is a public boat ramp on the Flint River in Newton. He talks admiringly about how the river changes in appearance three or four times during its 20-mile downstream run from Albany. "One time it almost looks like you're in a mountain brook."

During the return trip to Albany, he champions the work of the Southwest Georgia Water Resources Task Force. Its members come from all walks of life-farmers, researchers, city planners, utilities' managers-but they share his passion for protecting the water resources. Like him, they've decided that sharing information is the key to their region's future.

For an underwater cave diver, the importance of strategic planning cannot be overstated. Good divers plan by looking at everything that can go wrong and developing contingencies. DeLoach says that he and Exley would carefully talk through every stage of a dive beforehand, picking things apart, so that they would be ready to face a critical moment if it arose.

That's what the people in southwest Georgia are facing: A critical moment in the life of their water resources.

- A four-year drought has resulted in record low flows and water levels in reservoirs and aquifers, water restrictions and bans, as well as domestic, agricultural, and municipal well failures.

- A decade-long water war between Georgia, Florida, and Alabama has produced little agreement on how much water should be set aside for drinking, industry, agriculture, and recreation. Because the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin is an important water source for metropolitan Atlanta, there is great concern about balancing urban growth versus rural economies versus Apalachicola Bay's seafood industry.

- A lack of regional planning in southwest Georgia. While metro Atlanta now has the first regional planning district in the state to address its water woes, its formal structure and organization won't work in rural Georgia where the biggest water users are individual farmers, not county or municipal entities.

The idea for the Task Force first struck Morgan Murphy in 1998. He recalled an Albany chamber of commerce water committee in the 1970s that dealt with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' proposal to build a dam at Sprewell Bluff, upstream on the Flint River. To the relief of water users downstream, then-Governor Jimmy Carter vetoed the dam project, citing environmental concerns and misleading statements by the Corps of Engineers. As a result, the Flint continued to be one of the few rivers in the lower 48 states that extend longer than 225 miles without being dammed.

Murphy realized what the group's mission should be after he invited Dr. Elizabeth Blood, an education and outreach ecologist at the Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, to address a meeting of Albany chamber executives.

Liz Blood spoke eloquently about how the water crisis affected industry, municipalities, recreation, agriculture, and health. After her 30-minute talk, the executives kept her busy answering questions for another two hours.

"It dawned on me then what our mission should be-a regional committee to educate folks about water," said Murphy.

In the past, misunderstandings between different water users have dominated regional discussions over water. Murphy and Blood realized that if they could identify leaders in the region who represented each of the stakeholders, they might be able to open a dialogue that would clear the air of misgivings.

Jim Hook would represent agricultural research as a professor of soil and water management at the University of Georgia's National Environmentally Sound Production Agriculture Laboratory (NESPAL). Murray Campbell, Hal Haddock, and Mike Newberry would represent farmers. Woody Hicks, a 30-year veteran of the U.S. Geological Survey, would bring his expertise on groundwater issues to the table. Jimmy Knight and Ralph Powell would stand in for utilities. Other members of the Task Force included Dan Bollinger of the Southwest Georgia Regional Development Center, Susan Reyher of the Dougherty County Health Department (and dive partner of DeLoach), Glenn Singfield of the Albany Area Chamber of Commerce, and John Sperry, a former Albany city engineer.

Paul DeLoach, because of his affiliation with Miller Brewing and his national reputation for underwater exploration, would represent industry.

As one of its first responsibilities, the newly created Task Force group decided to hold "water summits," which would consist of an educational experience and a facilitated discussion. But rather than simply send out an open invitation to the summits, the Task Force opted for a bit of strategic planning.

"We wanted to find community leaders in each of the 30-plus counties in southwest Georgia that represented each of the stakeholder groups," says Blood.

Each member of the Task Force was asked to find one or two leaders in his/her profession (farming, industry, etc.) in each county. Then the Task Force sent out personal invitations to these individuals letting them know that they were chosen as a community leader.

At the first summit in January 1999, over 300 participants showed up. It was a huge success. The attendees discussed basic issues and concerns, and began talking about a regional focus.

Six more summits have followed, each one averaging about 150 invited leaders and another 100-300 attendees from the general public. The sessions have ranged from dealing with the formation of a regional water authority, to the thorny issue of water markets and water rights, to the effects of building regional reservoirs in the Flint River Basin.

John Sibley of the Georgia Conservancy believes that one of the most positive achievements of the Task Force has been developing leadership in the agricultural community around water issues.

"Out of that process there's a better dialogue between the agricultural community and other communities of interest," says Sibley.

John Sperry believes that one of the major contributions of the Task Force has been to let the "other Georgia" know what the problems of southwest Georgians are.

"Most of our laws come down from Atlanta. And Atlanta's problems are totally different from ours. They drink surface water-we rarely drink surface water here. It's just a totally different environmental setup."

After a total of seven summits thus far, the Task Force is now being viewed as a model for the rest of the state and has drawn financial support from the governor. Several Task Force members are working with new groups in the Suwanee River and Savannah River basins.

"I am intensely proud of what they are doing," says Bob Kerr. "They are good people who have come together and are trying to systematically understand what the issues are relative to water in their part of the world. They want to systematically work through those issues, looking for solutions-as opposed to controversy."

Blood credits DeLoach with being the inspiration behind the process. "It was Paul who kept saying, `Focus on process. Don't be constrained by what we've done in the past or traditional thinking.' Because of that, I think we've been able to assist in things that no one could have ever imagined happening."

DeLoach says the future tests of the Task Force will be to understand why people need to use water-the economic and social factors-and how to make wise decisions so we can have a sustainable supply of water.

But will people return to business as usual if the drought is over tomorrow?

DeLoach pauses, then rubs his earlobe thoughtfully. "It's human nature, I suppose, to make changes during times of crisis. But I think people recognize that we want economic growth, and we want clean rivers and streams.

"Our reputation is driven by our values. So, how does the world now see us? I think the world sees some southern states as users and takers. But I think Georgia would like to be known as a 'giver' and still have economic prosperity and be a great place to live with beautiful rivers, clean air, and sustainable water resources. That's the kind of reputation we'd like to have."

Go back to previous page. Go to The Flint River contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]