Virginia's

Western Highlands

Virginia's

Western Highlands  Virginia's

Western Highlands

Virginia's

Western Highlands Three mountainous counties on Virginia's western border are known as Virginia's Western Highlands. Formerly, this area was known as The Alleghany Highlands. But confusion arose. The Allegheny Mountains are a section of the Appalachian Mountains running northwest/southeast along the adjoining borders of Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. Did the term "Alleghany Highlands" refer to the entire Allegheny Mountain range though the spellings were different? Did it mean just Alleghany County, which has the same spelling of "Alleghany"? Or did Alleghany Highlands mean the three western counties of Bath, Highland, and Alleghany most closely associated with the Allegheny Mountains?

For marketing purposes, chambers of commerce and tourist bureaus needed to come to an agreement. They chose "Virginia's Western Highlands" for the three-county area and abandoned the word "Alleghany" and its confusing spellings. Use of the word still lingers. For no matter how it's spelled—even "Alliganey" can be found on old scouting maps—the Algonquin Indian word for "endless" inspires wanderlust.

On the west side of Alleghany, Bath, and Highland counties, Allegheny Mountain rises steeply to more than 4,000 feet to meet the West Virginia line at the crest. The ridgeline becomes higher on its northward run, reaching 4,100 in the remote Laurel Fork area northwest of Monterey.

On the eastern side of this formidable ridge are hundreds of thousands of acres of mountains and river valleys open to the public. Two ranger districts of the George Washington National Forest [Fig. 25]—the James River and Warm Springs districts—brim with campgrounds, hiking trails, picnic areas, and more. Lake Moomaw, which spreads across the Alleghany/Bath border, offers water sports, fishing, and recreation. The Gathright Wildlife Management Area adjoining the recreation areas of Lake Moomaw provides inroads to deer, turkey, and ruffed grouse habitat. Virginia Power provides a recreation area and fishing on Back Creek below its pump storage reservoir in northwestern Bath County. Laurel Fork Special Management Area invites quiet study.

Douthat State Park [Fig. 28] and Rough Mountain Wilderness [Fig. 23(4)] in southeastern Bath County offer yet more choices. One can hike, swim, paddle a canoe, and camp in the park where there are restaurants, running water, shelter, and human companionship. There's also the solitude of undisturbed backcountry wilderness.

Headwaters for the historic James River lie in the Highlands in the cold-water trout fisheries of the Jackson River, Bullpasture River, and Back Creek and in the warmer Cowpasture River. Scenic drives, bed and breakfast inns, quaint villages, mountain crafts, and a plush resort town add to the list of things to see and do in the Highlands. Interstate 64, VA 39, and US 250 lead through mountain gaps to run east-west through the Highlands. VA 42 and US 220 access these counties from the north and south.

[Fig. 22(1)] On a steep, shale cliff between Covington and the West Virginia line, Johnson Creek Natural Area Preserve protects one of Virginia's finest examples of shale barren habitats. Here, on steep precipices that rise some 300 feet above Johnson Creek, gnarled and stunted pines, cedars, and oaks struggle to survive in a harsh environment. More than a dozen endemic species—plants that occur only on shale barrens—cling to life on the unstable slopes. At least eight plants that are rare in Virginia have adapted to the shallow, nutrient-poor soil. An example is white-haired leatherflower (Clematis viorna), which takes its name from white, feathery seed tips.

Shale barrens are found mainly in the Valley and Ridge province of western Virginia, eastern West Virginia, and southern Pennsylvania. The rare community is characterized by steep eroding slopes with thin soils and surface temperatures that may reach 150 degrees in summer. The barrens usually face south and often occur where a bend in a river has eroded banks.

Shale barrens lie in what is called a rain shadow. Most of the East's precipitation is delivered by clouds formed over the Gulf of Mexico and blown inland from the southwest. When these clouds reach the Appalachians, they are forced upward and most of their moisture is released quickly. By the time clouds make it up and over the mountains, they have less moisture left for slopes on the east side—slopes in the rain shadow. These slopes, including shale barrens, receive significantly less precipitation because they must rely on rain from Atlantic hurricanes and northeasters powerful enough to cross the Blue Ridge.

Many

of the plants that adapt to these desertlike conditions are plants you might

find in a rock garden such as stonecrop (Sedum sarmentosa) and other

sedums, alumroot or palace purple (Heuchera americana), and moss phlox

(Phlox subulata). On the bluffs, stiff reindeer lichen covers almost

every inch of ground not taken up by a twisted pine, cedar, rotting adelgid,

or hollow stump. These plants have mechanisms to endure the heat, sun, and poor

soil. Some have thick, waxy leaves to prevent water loss. Others have hairy

stems and leaves to shade the plant from the intense sun. Deep extensive root

systems on many plants help claim a purchase in the loose shale.

Many

of the plants that adapt to these desertlike conditions are plants you might

find in a rock garden such as stonecrop (Sedum sarmentosa) and other

sedums, alumroot or palace purple (Heuchera americana), and moss phlox

(Phlox subulata). On the bluffs, stiff reindeer lichen covers almost

every inch of ground not taken up by a twisted pine, cedar, rotting adelgid,

or hollow stump. These plants have mechanisms to endure the heat, sun, and poor

soil. Some have thick, waxy leaves to prevent water loss. Others have hairy

stems and leaves to shade the plant from the intense sun. Deep extensive root

systems on many plants help claim a purchase in the loose shale.

The preserve was acquired by The Nature Conservancy on behalf of the Commonwealth of Virginia as a Partners in Conservation Project. Johnson Creek was dedicated as a Virginia Natural Area Preserve in 1990 to be managed by the Department of Conservation and Recreation. The pine-covered bluffs are visible from VA 661 about 3 miles northwest of the Alleghany County town of Callaghan. The preserve is operated as a satellite of Douthat State Park. Until public access is developed, anyone interested in learning more about it should contact the park superintendent. At the top of the bluffs, the shale ground between the towering rock cliffs gradually becomes steeper as it slopes toward the valley below, making it dangerous for hikers. A person could begin to slide and not be able to stop.

Virginia probably contains more shale barrens than Pennsylvania, Maryland, and West Virginia combined. Above Potts Creek south of Covington (also in Alleghany County) is another example of this habitat. The 9-acre Potts Creek Shale Barren was acquired by The Nature Conservancy in 1986. Three rare species endemic to this south-facing slope are chestnut lipfern (Cheilanthes castanea), Kate's mountain clover (Triflium virginicum), and Virginia nailwort (Paronychia virginica). Visitation is also restricted here because of the difficult terrain and fragile plant community.

Historic

Inns of the Western Highlands

Historic

Inns of the Western Highlands Highland Inn. [Fig. 26(6)] With its country charm and Victorian architecture, the Highland Inn on Main Street in Monterey has gained a place on the National Register of Historic Places. While in Monterey, visit the nearby Maple Museum's exhibits on the making of maple syrup. The museum is on VA 220 south of downtown.

The Homestead. [Fig. 26(28)] For more than 200 years, visitors have sought out The Homestead at Hot Springs for recreation. Built in 1766, the inn served first as a refuge for those who sought the healing powers of the area's warm springs bubbling from the ground. Several presidents have stayed at The Homestead. The Japanese Embassy staff in Washington, D.C., was interned in these grand quarters during World War II. This National Historic Landmark is located on US 220 between Covington and Warm Springs. Golf courses, tennis courts, riding trails, sporting clays, ski slopes, and four-star dining have been added to the warm baths in more modern times.

Longdale Inn. [Fig. 23(15)] Formerly the home of ironmaster William Firmstone, the Longdale Inn is located at the heart of the Longdale Furnace Historic District west of Lexington. It makes a comfortable base of operations for exploring the mountains, trails, streams, and backroads here. The exterior of the 1873 Victorian structure, built when Ulysses S. Grant was president, is painted dusty rose. Inside, original brass carbide chandeliers hang from 11-foot canvas ceilings trimmed in laurel leaf, and floor-to-ceiling windows offer mountain views.

Milton Hall Bed and Breakfast Inn. [Fig. 23(2)] Constructed in 1874, this National Historic Landmark was built on the national forest border south of Lake Moomaw. The English country manor has many gables, buttressed porch towers, and Gothic trimmings.

Hidden Valley Bed and Breakfast. [Fig. 26(24)] If this pre—Civil War plantation house on the Jackson River looks vaguely familiar, it might be because it's the site of the 1992 filming of Sommersby, with Richard Gere and Jodie Foster. Using bricks made of mud from the banks of the Jackson River, slaves built the mansion in 1748 for Jacob Warwick. The Warwick mansion, or "Warwickton" as it was called, is listed in the National Register of Historic Homes and has been converted to a bed and breakfast in recent years. An interpretive center in the summer kitchen is open weekends. The inn is located on national forest land on the Jackson River, west of Warm Springs in Bath County.

[Fig. 22(4)] Located west of Covington in Alleghany County, Humpback Bridge is the nation's only surviving curved-span covered bridge. Yet three such bridges, bowed upward in the center, are thought to have been within a mile of each other in this area. The 100-foot span was constructed in 1857 as part of the Kanawha Turnpike in an attempt to link easterners with the Mississippi River Valley. In 1929 when a new bridge was built nearby, the bridge was abandoned and left to slowly decay. In 1954, Covington businessmen and women found the funds necessary to restore it. A 5-acre wayside was set aside where visitors can enjoy picnic lunches and imagine the clip-clop of horses' hooves echoing from the bridge.

[Fig. 23(17)] Equestrian events such as rodeos, sales, competitions, and shows are held year-round in the indoor coliseum and outdoor rings of the Virginia Horse Center. The center is located just north of Lexington off VA 39 at the intersection of I-64 and I-81.

[Fig. 23(7)] Falling Spring is a rarity—an incredibly beautiful waterfall that requires very little effort to view. The falls are at a pullover on US 220 about 7 miles north of Covington. Here, 7,000 gallons of water a minute plunge over a sheer, 200-foot bluff to the rocks below. A fine mist hangs in the air providing moisture for such plants as jack-in-the-pulpit, touch-me-not, and a variety of ferns.

Thomas Jefferson once admired the scene and called Falling Spring "the only remarkable cascade in this country." (In fairness to other falls, he probably intended "country" to mean "area.") The major source of the cascade is a warm spring that rises to the surface about 1 mile north of the falls. The water rises along a fault line through Falling Spring Valley's underground honeycomb of limestone caves, picking up minerals from the rock.

White calcite crystals form on the edges of fallen leaves and twigs along the stream. Look for examples of this phenomenon on the east side of the highway, just above the falls. The calcite—the same material in stalactites hanging from cave ceilings—is evidence of water that is super-carbonated, or filled with minerals such as calcite and dolomite. The warm water runs under the road near the pullover and then over the erosion-resistant Tuscarora sandstone cliff and drains the area between Warm Springs Mountain and Little Mountain. Falling Spring is the name not only of the falls and the valley it drains but also of the creek that carries the water and the community where the water enters the Jackson River.

[Fig. 23(11)] Normally, water bubbling from underground springs is cold. But in areas where the earth's crust is faulted and folded, cracks allow water from much deeper to rise to the surface. At these deeper levels, basement rock under tremendous pressure is hot. If water rises quickly enough, it may reach the surface before it cools.

Many

hot springs, or thermal springs as they are also called, contain minerals that

people drink or bathe in for their supposed curative powers. Bath County takes

its name from its many such springs. A look at a map shows a 16-mile-long line

of thermal springs concentrated along US 220. About 7 miles north of Covington,

US 220 enters Falling Spring Valley. From south to north, the highway passes

Falling Spring, Healing Springs, Hot Springs, and Warm Springs. A fracture in

the under- lying rock in the valley center reaches down to deep limestone rock

of the early Paleozoic Era—rock that is 500 million years old or older.

The springs that are forced to the surface here are much warmer than those in

the sides of the valley where the fractures do not go nearly as deep.

Many

hot springs, or thermal springs as they are also called, contain minerals that

people drink or bathe in for their supposed curative powers. Bath County takes

its name from its many such springs. A look at a map shows a 16-mile-long line

of thermal springs concentrated along US 220. About 7 miles north of Covington,

US 220 enters Falling Spring Valley. From south to north, the highway passes

Falling Spring, Healing Springs, Hot Springs, and Warm Springs. A fracture in

the under- lying rock in the valley center reaches down to deep limestone rock

of the early Paleozoic Era—rock that is 500 million years old or older.

The springs that are forced to the surface here are much warmer than those in

the sides of the valley where the fractures do not go nearly as deep.

The Homestead [Fig. 26(26)] at Hot Springs operates an indoor pool and two restored eighteenth- and nineteenth-century bathhouses (separate facilities for men and women) fed by thermal springs. The octagonal wooden bathhouses are located beside the road at Warm Springs. The men's opened in 1761 and the women's in 1836. Steam rises from the warm water where the stream flows beside the parking area on US 220. The temperature in the rock pools is a balmy 98.6 degrees.

[Fig. 25] The 164,260 acres of the James River District spread across all of Alleghany County and take in the upper James River in northern Botetourt County. The district is the southernmost of the George Washington National Forest. To the west, Alleghany Mountain separates the district from West Virginia and the Monongahela National Forest. Interstate 64 passes east/west through the center of the district. The highway connects the western mountains with Interstate 81, running north/south in the Shenandoah Valley.

Generally, private lands lie in the lush valleys along the major creeks and rivers, while the mountains are the public's to explore and enjoy. Public recreation areas are clustered at the southern end of Lake Moomaw (the northern end is in the Warm Springs District) and in the Longdale Furnace area on the east side of Alleghany County. The district's Low Moor Shooting Range, between Clifton Forge and Covington, is open year-round. Shooting lanes of various lengths provide a chance to sight in a gun or practice target shooting. The district office in Covington can provide not only a district map and brochures on the most popular trails but also a sheet on any other trail of interest to a hiker.

Hiking the James River District. Hiking opportunities on 80 miles of trails are almost limitless. Brochures at the ranger district office give detailed mile markers of the more popular trails.

Allegheny Trail. [Fig. 22(2)] Twelve miles of the Allegheny Trail pass through the James River district. This strenuous long-distance trail follows the Eastern Continental Divide in the rugged Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia and Virginia. When completed, the yellow-blazed footpath will extend 330 miles from Preston County, West Virginia, near the Pennsylvania border, to the Appalachian Trail in Monroe County, West Virginia. The trailhead is 12 miles west of Covington at Exit 1 off I-64.

Fore Mountain Trail. [Fig. 22(3)] The 14.8-mile Fore Mountain Trail is one of the best-known trails, and it gets heavy use from hikers, Douthat Lake campers, horseback riders, and ATVs. The blue-blazed path travels through upland hardwoods and pines typical of high- elevation forests of the Alleghany Mountains and opens to expansive views. Look for a variation on woodland wildflowers and wildlife at several grassy areas and at the Smith Creek crossing. Smith Creek is stocked with brook trout.

The strenuous trail begins at Dolly Anne Work Center just off US 60 east of Covington. The end is near Douthat State Park where it becomes the Middle Mountain Trail and continues north another 5.5 miles to FR 125. Good areas for primitive camping are at mile 8.5. Parking is available at mile 10.2, where the trail crosses VA 606. A side trail, the scenic 9-mile Dry Run Trail, intersects Fore Mountain Trail at mile 6.1 then heads back to Covington. The Dry Run Trail (also blue-blazed) passes near Big Knob, the highest point in Alleghany County (4,072 feet). The trailhead is at the end of Cyprus Street in Covington.

Eastern National Children's Forest. [Fig. 23(21)] The Eastern National Children's Forest is a unique site in the southern portion of the James River District. In 1971 a wildfire destroyed trees on 1,176 acres on Potts Mountain, about 22 miles south of Covington. On April 28, 1972, on the 150th anniversary of Arbor Day, more than 1,000 children from Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania planted shortleaf pine trees on the charred site. The planting was one of three National Children's Forests originally established in the United States.

The

names of the children participating in the forest restoration are stored in

a time capsule to be opened in the year 2072. Near the time capsule is a monument

to the children. The stone monument is at the trailhead for a paved .25-mile

loop trail (handicapped accessible) which offers a glimpse of the trees, wildflowers,

and animals now living in the young forest. Many different plants have developed

in the understory including grapevine, black gum, various oaks, and greenbrier.

The

names of the children participating in the forest restoration are stored in

a time capsule to be opened in the year 2072. Near the time capsule is a monument

to the children. The stone monument is at the trailhead for a paved .25-mile

loop trail (handicapped accessible) which offers a glimpse of the trees, wildflowers,

and animals now living in the young forest. Many different plants have developed

in the understory including grapevine, black gum, various oaks, and greenbrier.

The Forest Service is considering construction of two additional loop trails—a 1.5-mile loop and a 3.5-mile loop—starting and ending on the existing trail.

Longdale Recreation Area. [Fig. 23(14)] Longdale Recreation Area is a day-use area in the James River District, east of Clifton Forge. A small lake for swimming and access to several hiking trails that lead to spectacular views are highlights. Longdale was constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the late 1930s and was called Green Pastures. The hand-built dam, bathhouse, picnic shelter, and two restrooms are original buildings.

Green Pastures was one of very few such areas built for African Americans who were prevented from using forest facilities during the days of segregation. It was heavily used. In 1963 it was opened to all races and the name was changed to Longdale.

Trails here include Anthony's Knob Trail, Blue Suck Run Trail, YACCer's Run Trail, and North Mountain Trail. Rock cliffs and ridgetops are visible from several areas, and thickets of rhododendron bloom in May. The James River District office can supply trail maps. Some trails are in poor condition and have faded or nonexistent blazes.

Highlands

Scenic Auto Tour. [Fig.

27, Fig.

23(16)] The James River District's auto tour was designated a National Forest

Scenic Byway in 1989. It deserves the recognition. The Highlands Scenic Auto

Tour is a 19-mile loop between Clifton Forge in Alleghany County and Interstate

64 at Lexington. The drive combines a mix of mining and logging history, fantastic

views, craggy cock's comb rock formations, century-old poplars, hiking opportunities,

and a ride along a wilderness border.

Highlands

Scenic Auto Tour. [Fig.

27, Fig.

23(16)] The James River District's auto tour was designated a National Forest

Scenic Byway in 1989. It deserves the recognition. The Highlands Scenic Auto

Tour is a 19-mile loop between Clifton Forge in Alleghany County and Interstate

64 at Lexington. The drive combines a mix of mining and logging history, fantastic

views, craggy cock's comb rock formations, century-old poplars, hiking opportunities,

and a ride along a wilderness border.

Just south of the tour route, on the western side of VA 269, stand the 100-foot brick smokestacks and remains of one of the first iron blast furnace operations in the South. Iron forged here was used in making the Confederacy's Merrimac (or CSS Virginia), America's first ironclad ship. Stops on the tour relate to this furnace.

Although known for its remoteness, the tour is half on one side of Interstate 64 and half on the other. But visitors forget the interstate immediately as the road climbs North Mountain. In fact, this area is a fine place to see wildlife, including white-tailed deer, wild turkey, ruffed grouse, and occasionally bobcats. In September and October, look for migrating hawks and other birds of prey above the open bluffs on North Mountain. If time allows for just part of the drive, the most scenic route is on the southeastern side of I-64 on North Mountain. This road is known locally as Top Drive. The view to the east from the sheer cliffs at the top is unmatched. Stunted shadbush (serviceberry) trees cling to ledges on the precipitous bluffs. In April, their white blooms against the valley floor far below are photographic material. Brochures available at the district office (and sometimes at the information boards at each end of the tour) provide important information on the views and the area's history.

Mile 2.4: Rhododendron Trail. [Fig. 27(6)] This short walk is handicapped accessible. The rhododendrons here are about 100 years old. The twisted, hard wood has withstood untold ice storms and gale-force winds. The trail leads to an overlook with a view of the Rich Hole Wilderness.

Mile 4.2: Cock's Comb. [Fig. 27(8)] The ragged rock formation above a moderately steep but short (.25-mile) trail here resembles a cock's comb. The rock is composed of erosion-resistant sandstone that was originally deposited at the bottom of an ancient ocean. The horizontal layers were turned vertically and pushed up from the valley floor by pressure from shifting continental plates.

Mile 5.8: North Mountain Overlook Trail. [Fig. 27(12)] An easy path leads to views from rocky bluffs of Lake Robertson and the valley of Buffalo Creek. To the northeast are two rounded knobs called Big House Mountain and Little House Mountain. To the southeast, the Short Hills range rises abruptly from the valley floor. The Blue Ridge Mountains are in the distance.

Mile 6.7: Collierstown Road. [Fig. 27(13)] Go right. This road and hand-laid rock retaining walls remain much as they looked in 1826 when they were constructed. The road provided access for a pig iron furnace and iron mines in the valley below and subsequently was used by farmers to take produce to market.

Mile 9.5: Century-old poplars.

Mile 9.9: West Entrance Turnaround and Information Board. Depressions in the earth are remnants of charcoal hearths. If you had stood here 100 years ago, the hills would have been devoid of large trees, and charcoal hearths would be burning. The trees were cut to fuel the pig iron furnaces.

Mile 16.1: Rich Hole Wilderness. [Fig. 27(5)] The wilderness borders the road on the northeast side.

Rich Hole Wilderness. [Fig. 27(5), Fig. 23(9)] This 6,450-acre wilderness is located about 15 miles west of Lexington in the James River District of the George Washington National Forest, tucked in the northeastern spur of Alleghany County and western Rockbridge County. The shape of Rich Hole is a long northwest/southeast-oriented rectangle, protecting the watersheds of Alum Creek on the northern end and the North Branch of Simpsons Creek on the southern end. The Bath County line marks the western boundary. US 60/VA 850 and Interstate 64 roughly parallel the eastern boundary.

Established by Congress in 1988, the wilderness is home to a diverse array of flora and fauna, including stands of old-growth hardwoods in fertile, northeast-facing coves in the headwaters of Alum Creek. In fact, Rich Hole takes its name from the rich soils in these coves or "holes" on Brushy Mountain. Cove hardwoods here include northern red oak, basswood, tulip poplar, sugar maple, green ash, and cucumbertree. The trees are widely spaced, reaching heights of 130 feet or more, with carpets of ferns and mosses in the dark forest below. The parklike appearance in the open understory is typical of mature cove forests. In the colorful understory of the rich coves, where the canopy has not shaded them out, are redbud, flowering dogwood, and blueberry and evergreen heath thickets of rhododendron, fetterbush, and mountain laurel. In a cove forest, bird species are as diverse as species of trees and shrubs. The large, colorful pileated woodpecker may fly from tree to tree ahead of hikers or sound its raucous cackle from somewhere just out of sight. Darting about in the understory, small birds such as the golden-crowned kinglet and various warblers may be spotted. Salamanders and small, ground-dwelling mammals such as the white-footed mouse dwell in the mosses and ferns of the forest floor.

White-tailed deer, ruffed grouse, and wild turkey are more likely to be spotted outside of old-growth areas of the forest where trees are smaller and undergrowth thicker—in other words, where there is food and cover. Most of the dry slopes of Brushy and Mill mountains are covered with mixed hardwoods such as chestnut oak, American beech, and hickory and evergreens that include pitch pine, Virginia pine, and white pine. Tenacious table mountain pines grow on exposed ridges. The trees are in various stages of succession as the forest recovers from previous logging. Signs of earlier iron mining remain throughout (see Highland Scenic Auto Tour).

Hikers on the Rich Hole Trail pass near the old-growth hardwoods in the Alum Creek drainage and also by a huge black cherry and a stand of large Eastern hemlocks in the North Fork drainage. The White Rock Trail, which forms the southern boundary of the wilderness, has very large oaks.

Rich Hole Trail. [Fig. 27(4), Fig. 23(10)] This is the only maintained trail within the wilderness. From the southern trailhead, the path makes a gradual climb up the North Branch of Simpsons Creek to the crest of Brushy Mountain then makes a right turn in the area of the old-growth forest and steeply descends the mountain's eastern slope to the upper trailhead. An old pair of nonslippery shoes will help the hiker make the many crossings of North Branch. Along the trail, the forest opens to impressive views at rocky ledges.

Another possibility is a shorter but steep trek from the northern trailhead up Brushy Mountain to the old-growth forest and back. The old-growth hardwoods are about a mile from the northern trailhead. They are on the north end of the trail near the summit where a ridge separates the two watersheds.

Douthat

State Park

Douthat

State Park [Fig. 23(8), Fig. 28, Fig. 21(28)] The 4,493 acres of Douthat State Park lie between Warm Springs Mountain and Beards Mountain in southern Bath County. The cold mountain waters of Wilson Creek flow into little, 50-acre Douthat Lake, the park's focal point. Wilson then heads south to join the Jackson River at Clifton Forge. The park is known for its spectacular mountain scenery, trout fishing, swimming beach, many wooded hiking trails, attractive campgrounds, and rustic but comfortable cabins. It's also ideally situated for exploration in the surrounding Warm Springs and James River ranger districts of the George Washington National Forest.

One of Virginia's original six state parks, Douthat still benefits from the meticulous construction of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The CCC was established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 to provide Depression-era men with work. At Douthat, an estimated 600 men cleared trails and built a dam and spillway, log cabins, guest lodges, a restaurant, an information center, a swimming beach, and picnic areas.

The work has held up over the years—so well, in fact, that on Douthat's fiftieth anniversary in 1986, the park was recognized as a Registered Historic Landmark. Look for such adornments as hand-carved wooden doorknobs and hinges and hand-wrought iron door and shutter latches. Where tributary streams go beneath the road, often hidden from view, are expertly crafted culverts with stone archways.

Diners in the Lake View Restaurant [Fig. 28(12)] overlooking the 50-acre lake can admire the work of the CCC as they down a slice of homemade apple pie.

Besides the Buck Lick Interpretive Trail [Fig. 28(11), Fig. 23(12)] on dry land, Douthat has a watery self-guided trail by paddleboat around Douthat Lake. Visitors can rent a boat at the boat concession near the beach and spend a leisurely morning or afternoon discovering the lake's beaver activity, cattails, dragonflies, fish, and bird life. The park has a camp store adjoining the restaurant. Nearby Clifton Forge has laundromats, grocery stores, and pharmacies.

Flora

and Fauna at Douthat. Trilliums, which may be found throughout the woods

at Douthat in the spring, are particularly abundant in Campground A. Look for

the bright pink petals of low-growing gaywings or fringed polygala (Polygala

paucifolia) in the cabin area in May and June. The flower belongs to the

milkwort family of plants which, according to folklore, will increase milk production

when fed to cows or nursing mothers.

Flora

and Fauna at Douthat. Trilliums, which may be found throughout the woods

at Douthat in the spring, are particularly abundant in Campground A. Look for

the bright pink petals of low-growing gaywings or fringed polygala (Polygala

paucifolia) in the cabin area in May and June. The flower belongs to the

milkwort family of plants which, according to folklore, will increase milk production

when fed to cows or nursing mothers.

Both pink lady slipper (Cypripedium acaule) and yellow lady slipper (Cypripedium calceolus) grow at Douthat. The pink variety prefers dry woods. The yellow favors limestone wetlands and rich woods. It is more rare than the pink in Virginia. Neither should be picked.

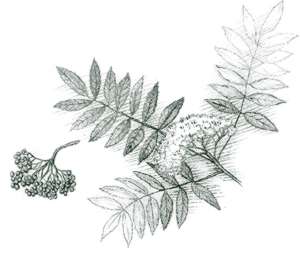

Other woodland flowers here include bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), crested dwarf iris (Iris cristata), mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum), and rue anemone (Anemonella thalictroides). Large flame azalea (Rhododendron calendulaceum) bloom in the boat launch area. In late summer or early fall, park visitors can sample the delicious fleshy fruit of the little pawpaw tree behind Creasy Lodge. They can, that is, if raccoons, opossums, squirrels, and black bears don't beat them to it.

Flowering dogwood, mountain laurel, autumn olive, rhododendrons, and American barberry add color and interest to the understory. Barberry (Barberis canadensis) is a low shrub that has thorns at the base of the leaves. Its beautiful red fruits are sought throughout the fall and winter by many birds including ruffed grouse and bobwhite. Running cedar and Christmas ferns carpet the forest floor with green even in the dead of winter.

Wild turkey are common at Douthat. The gobbling of the males on the mountainsides echoes across the lake in early spring. Occasionally, the "perk-perk" of the females can be heard. White-tailed deer and gray foxes and other woodland animals come to drink from the lake at dusk. Beaver and muskrat leave a V trail as they cross the open water. Canada geese with goslings and wood ducks with ducklings poke about the lake edges in spring. From a favorite perch on a dead limb, the handsome kingfisher studies the water. If a minnow swims too close to the surface, the kingfisher will plunge headlong into the lake to catch it. Red-tailed hawks and even an occasional bald eagle circle the air above the lake.

Camping and Lodging at Douthat State Park. To camp near the lake, ask for the Campground A. Boat mooring is available here also. Wilson Creek, which flows through the campground, will attract curious children and adults to look for salamanders, minnows, and streamside wildflowers. A fly-fisherman may wade the shallows searching for trout. If mayflies or caddisflies are hatching, he'll be casting a few feathers carefully tied to a hook to resemble the latest hatch. Campground C has several sites with more privacy. Campsites tend to be small and have picnic tables, grills, and lantern posts. Hardwoods and pines provide shade.

The rustic Douthat State Park cabins are well spaced among big shade trees. Nothing noisier than the hollow scraping of an oar against a canoe down at the lake disturbs the tranquility of a fall morning spent rocking and reading. The cabins have newly installed air conditioning and heating, but a glowing fire in the fireplace may be all the heat necessary in spring and fall.

Hiking and Biking at Douthat State Park. The 6-foot-wide trails built by the CCC remain today to invite hikers and bikers to enjoy the lake path, find Stony Run and Blue Suck falls, or climb the difficult path to Tuscarora Overlook. Lengths of the 24 trails vary from a mere .3 mile to 4.5 miles, but an infinite number of connections in the 40 miles of trails at Douthat make much longer hikes possible. Douthat has more trail mileage than any other state park in Virginia. Also, several paths lead to longer trails in the surrounding George Washington National Forest.

Stick to more level trails around the lake for the easier hikes. Trails up Middle Mountain to the west and Beards Mountain to the east offer strenuous climbs. Many hikers take cameras along for the stunning mountain and lake photo opportunities. From Beards Mountain, one can see the Cowpasture River to the east and Rough Mountain Wilderness beyond.

Douthat has 12 suck licks which are small springs formed when salty sulphur water drains from underground rock. Deer and other wildlife are drawn to these springs to lick the salty water for sodium. The Buck Lick Interpretive Trail, Blue Suck Falls, and Claylick Draft (on Beards Mountain) take their names from these springs. None of the suck licks are accessible by trail at this time. Douthat's trails are blazed and easy to follow. The park office has detailed trail maps. With the extensive networking of trails here, it's easy to become interested in the scenery and miss a connection. Bikers should ask which of the trails they are permitted to use and what safety requirements are.

Buck Lick Interpretive Trail. [Fig. 28(11), Fig. 23(8)] Pick up a $.50 booklet at the park office to explain the 17 learning stations on this easy, red-blazed loop. The trailhead is in the parking area near the entrance to the lakeside concession area. Allow about 50 minutes to enjoy the features and wildflowers along the trail. Included in the tour are such plants and animals as white pine, white and black oak, sassafras, American chestnut, rhododendron, lichens, squirrel, raccoon, white-tailed deer, and bobwhite quail.

Of course, interpretive trail markers cannot designate the many interesting insects, amphibians, ferns, wildflowers, and the like. For instance, the dogtooth violet (Erythronium americanum) grows on the Buck Lick trail. This member of the lily family has mottled green leaves with brown spots that give its presence away before the yellowish blossoms appear in early spring.

Heron Run Trail. [Fig. 28(6), Fig. 23(13)] This easy, blue-blazed trail is one of the most popular at the park for its lakeside scenery. In fall, red maples, yellow poplars, and evergreens reflect their colors in Douthat Lake. The trailhead is in the lakeside loop of Campground A.

Fishing at Douthat and Little Wilson Creek. [Fig. 28] Douthat is one of just three fee-fishing areas in Virginia. Twice a week, from April through October, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries stocks catchable-size rainbow, brown, and brook trout in Douthat Lake and a 4-mile section of Wilson Creek. The fee-fishing area extends above and below the lake to the national forest boundary. Anglers must have a Virginia fishing license and must pay a daily fee. A trout stamp is not necessary during the fee-fishing season but is required during the rest of trout season.

Douthat is an ideal place for children to learn to catch trout. Regulations have been modified to allow children 12 and under to fish without a daily permit if they are accompanied by an adult with a permit. The combined creel of adult and child may not exceed six trout. A small-children-only section has been set aside on Wilson Creek just below the dam. Good bass fishing and fair fishing for bluegill and catfish also keep anglers busy on the lake. Chain pickerel fishing is excellent, especially in October. The small lake is a place for anglers who like to cast from boats or shoreline without the wake and noise of gas-powered boats, which are not permitted.

Daily permits, trout stamps, and fishing licenses are available at the park boat dock or camp store.

[Fig. 25] The huge Warm Springs Ranger District (171,526 acres) occupies most of Bath County except the northeastern tip. The district also includes the western side of Highland County. For its entire 50-mile length, the district borders West Virginia's Monongahela National Forest. Several trails provide a backcountry connection between the two states.

Beautiful mountain scenery adds to the pleasure of fishing, wading, or swimming in Warm Springs District waters. Miles of hiking trails provide choices from easy riverside walks to remote backcountry climbs up steep mountainsides. Bolar Mountain and Bolar Flat recreation areas on the northwest side of deep Lake Moomaw are managed by the Warm Springs Ranger District (see Lake Moomaw). Hidden Valley and Blowing Springs recreation areas provide bases for investigating the cold trout waters of the Jackson River and Back Creek and their watersheds. The Walton Tract provides access to the warm waters of the Cowpasture.

Horseback riders have several options. The district office recommends the remote Laurel Fork area of Highland County for more experienced riders. Riders can choose from many trails and gated roads at the Hidden Valley area. The Lime Kiln and Hickman Draft/Beards Mountain areas get significant amounts of horse use. Maps and directions are available at the district office.

The

Cowpasture River and the Walton Tract

The

Cowpasture River and the Walton Tract [Fig. 23(5)] Anglers can try for smallmouth bass, rock bass, muskies, redbreast sunfish, and stocked muskies among the smooth, tawny-colored rocks of the shallow, crystal-clear Cowpasture River. The river flows through the east side of the Warm Springs District southward into the James River District. It joins the colder Jackson at Iron Gate, southeast of Clifton Forge, to form the James River. Just a short stretch of about 6 miles between US 60 and the confluence with the Jackson is legally navigable. But farther north (upriver) are two U.S. Forest Service public bank accesses. One is on VA 614 at the junction with VA 678 near Williamsville in northern Bath County. Another is a 3-mile section of the river where it flows through the Walton Tract of the James River District northeast of Clifton Forge. Canoe put-in and take-out points are provided. A swinging bridge across the river leads to the Beard's Mountain Trail and ultimately to Douthat State Park.

The Cowpasture and its tributary, the Bullpasture River, take their names not from domestic cattle but from the elk that once roamed western Virginia. (There's also a Calfpasture River across Shenandoah Mountain to the east.) The mountains and valleys were lush hunting grounds for Indians, especially the Shawnee. Researchers think the roaming elk herds were probably kept in balance until settlers arrived and the Indians acquired firearms. So clear is the water of the Cowpasture that a bluegill or watersnake casts a shadow against the smooth rock bottom even in deep pools. The river's clarity makes it a pleasure to wade, swim, fish, or just to watch aquatic life.

The water boatman, a bug with legs that work like oars, is a tiny predator on the water surface. Dragonflies and damselflies light briefly on reeds. A quiet approach is necessary to get close enough to identify them. These members of the family Odonata can be told apart by the position of their wings. The dragonfly resembles a little biplane with its two pair of wings held horizontally straight out from its body. The smaller, more fragile-looking damselfly holds its wings pressed together lying parallel to its back. Wood ducks and mallards are summer residents along the river. In the neighboring fields, the nasal "p-e-e-n-t" of American woodcocks in their courtship flights can be heard. Bobwhite quail, though declining throughout Virginia, still call. Wild turkey and ruffed grouse are common woodland birds.

More information and maps are available from the James River and Warm Springs ranger districts of the George Washington National Forest.

[Fig.

23(19)] Rough Mountain is an aptly named wilderness of 9,300 rugged acres

about 7 miles northeast of Clifton Forge in Bath County. It encompasses all

but the northeastern end of Rough Mountain. VA 42 borders Rough Mountain on

the northwest side. Pads Creek and the CSX Railroad are on the southeast border.

To the southeast are Mill and Brushy mountains and Rich Hole Wilderness, separated

from Rough Mountain by a tract of George Washington National Forest.

[Fig.

23(19)] Rough Mountain is an aptly named wilderness of 9,300 rugged acres

about 7 miles northeast of Clifton Forge in Bath County. It encompasses all

but the northeastern end of Rough Mountain. VA 42 borders Rough Mountain on

the northwest side. Pads Creek and the CSX Railroad are on the southeast border.

To the southeast are Mill and Brushy mountains and Rich Hole Wilderness, separated

from Rough Mountain by a tract of George Washington National Forest.

The steep terrain of Rough Mountain is covered mostly with an oak-hickory forest typical of dry Appalachian slopes. Elevations range from 1,150 feet on the Cowpasture River on the western side to 2,840 feet on Griffith Knob.

Crane Trail. [Fig. 23(3)] This unblazed path begins a mile north of parking area on east side and leads west across Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad and Pads Creek, a tributary of the Cowpasture River. It then steeply ascends Rough Mountain 1.6 miles to ridgetop suitable for camping (no water or other facilities). The trail leads down the other side of Rough Mountain about 1.4 miles toward VA 42. Posted signs mark the wilderness boundary and beginning of private property. Hikers without permission should turn back here. The trail terminates at a small parking area on private property along VA 42.

For those who like solitude and the challenge of wilderness travel, a 4.5-mile (one-way) bushwhack south along the ridgetop from the Crane Trail leads to Griffith Knob with its beautiful views. No water is available, so hikers should carry enough for the return trip.

Lake Moomaw. [Fig. 23(1)] Lake Moomaw is 12 miles long and covers 2,350 acres on the Bath County/Alleghany County border. Created with the construction of the 257-foot-tall Gathright Dam in 1981 for flood control, the lake has an average depth of 80 feet. Unlike many large bodies of water, gasoline-powered boats have not taken over this out-of-the-way lake. Canoes and kayaks have 43 miles of shoreline to range with no fear of bothering private property owners. The lake is surrounded by more than a million acres of George Washington National Forest and the 13,428-acre Gathright Wildlife Management Area (WMA).

Moomaw is home to 25 species of fish. Smallmouth bass are dominant at the lower end of the lake and in the headwaters. Three- and 4-pounders are common in the spring. Look for largemouth bass up to 5 and 6 pounds and catfish in the range of 10 to 16 pounds. Crappie fishing is outstanding. Sizzling in frying pans over evening campfires will be tasty crappie of 1.5 pounds or more. Anglers without boats fish around dock pilings for nice bluegill. Also, the state-record yellow perch (2 pounds, 3 ounces) came from Moomaw in 1995.

Stocked brown trout are growing to 2 or 3 pounds. The best time to catch them is from January to June before water levels are drawn down and temperatures increase. Neither a trout license nor a National Forest Stamp is required, but a Virginia fishing license is required. Trailered boats must be launched at ramps at Fortney Branch (southern tip), Bolar Flat (northwest side), or Coles Point (near dam). Hand-carry boats can be put in at McClintic Point on the northwest side near the upper end and at Midway Point between Bolar Flat and McClintic Point.

The attractive recreation areas north of the dam are managed by Warm Springs Ranger District. These include Bolar Mountain, Bolar Flat, and Greenwood Point. The James River Ranger District manages the southern end where popular Coles Point and Morris Hill recreation areas attract crowds on summer weekends. Arrive early in peak season to secure a campsite. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operates a visitor center at the dam.

Spectacular displays of wildflowers are scattered along the roadside and fields on the back entrance to Lake Moomaw along the Richardson Gorge Road (VA 603). Trillium, wild ginger (Asarum canadense), and columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) are among the many varieties. Land on both sides of this road is private.

Gathright Wildlife Management Area. [Fig. 23(1)] Gathright Wildlife Management Area's (WMA) 13,428 acres are divided into two tracts by Lake Moomaw. The largest tract is on the western side of the lake, and it lies on the eastern slope of Allegheny Mountain and the southern end of Bolar Mountain. Five parking areas on VA 600 along Mill Creek provide access to gated roads which are opened for hunting seasons. The other tract is on Coles Mountain on the eastern side of the lake.

Stands of oak-hickory and mixed oaks are the major forest types. In fertile hollows, tulip poplar grows. The area is managed by the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries for forest wildlife such as wild turkey, white-tailed deer, ruffed grouse, and gray squirrel. Management practices include small clear-cuttings, plantings of grass and clover for wildlife openings, and tree thinning to enhance production of hard mast such as acorns, an important source of food for game animals.

The combined resources of lake, national forest, and WMA attract a variety of animals that need large tracts of undeveloped land. An example is the endangered bald eagle, a species uncommon to the mountains of Virginia. Eagle perches have been built in secluded areas to encourage eagles to use the lake area. The management agencies have also built at least five waterfowl islands below the McClintic Bridge. Ducks and geese are now using these islands for nesting. Natural islands within the lake are also managed for waterfowl nesting and feeding areas. Canada geese in particular have benefitted from these sites.

Gathright WMA and Bolar Flat, Bolar Mountain, and Greenwood Point recreation areas: From junction of VA 39 and VA 220 just east of Warm Springs, go west 11.3 miles on VA 39 and turn left on VA 600. After 2.5 miles, WMA begins (look for yellow WMA signs and parking areas on right side for next 5 miles). At 7.5 miles road forks. Right fork leads to Bolar Mountain camping and picnicking and left fork (VA 603) leads to Bolar Flat boat launch and picnic area. Greenwood Point is a primitive campground that can be reached by boat or by hiking the 3.3-mile Greenwood Point Trail from Bolar Mountain.

Gathright Dam and Coles Mountain Recreation Area: From VA 220 at Hot Springs, go west 2.7 miles on VA 615. Turn left (south) on VA 605 and go 3 miles. After crossing the dam, take entrance road, FR 601.

Morris Hill Recreation Area and Fortney Branch (boat launch): Take Exit 16 from I-64 at Covington and take US 220 north 4 miles. Turn left on VA 687 and go north 3 miles. Turn left on VA 641 and go west 1 mile. Turn right on VA 666 and go north 5 miles. For Morris Hill, from VA 666 turn right on VA 605 and go 2 miles to entrance road, FR 603, on left. For Fortney Branch, turn left on VA 605 and follow signs 1 mile to launch.

In years past, the 19-mile stretch of the Jackson River between Gathright Dam on Lake Moomaw and Covington has provided high-quality trout fishing on a large river. However, disputes between property owners and fishermen make floating this section a dicey business. A recent decision by the Virginia Supreme Court upheld an old law on the books giving certain landowners along the Jackson the right to prohibit fishing through their property. In these areas, boaters can float through but not fish. Five public access sites have been developed where bank fishing is permitted, however. Otherwise, landowners' permission should be obtained. The first public access site, managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, is just below the dam spillway off VA 605. The second is Johnson Springs off VA 687. The third, Falling Spring, is off VA 721. The fourth is Indian Draft located off VA 687. The fifth is Petticoat Junction also located off VA 687.

[Fig. 26(21)] Hidden Valley, rich in history and pastoral charm, lies at the upper reaches of the Jackson River about 6 miles west of Warm Springs. This Bath County treasure is worth the trouble to find. The blue-green Jackson is famous among fly-fishermen for its stocked and native trout. Twenty miles of trails vary from easy footpaths that follow the river to strenuous climbs over Back Creek Mountain. Wildflowers typical of streamsides, fields, rock ledges, and forests find suitable habitat in Hidden Valley. Wildlife clearings attract white-tailed deer in early evenings. Bald eagles occasionally scavenge the riverbanks.

Reservations

are required to enter the grounds of historic Warwick Mansion, but you can see

it from the river. Hidden Valley Campground, with its large, sparsely forested

sites, is a favorite for fly-fishermen interested in the Jackson which flows

beside the campground.

Reservations

are required to enter the grounds of historic Warwick Mansion, but you can see

it from the river. Hidden Valley Campground, with its large, sparsely forested

sites, is a favorite for fly-fishermen interested in the Jackson which flows

beside the campground.

Blowing Springs Campground [Fig. 26(25), Fig. 29] is located on VA 39 where O'Rourke Draft flows into Back Creek, another stocked trout stream. Hunters, fishermen, and those looking for private sites away from crowds enjoy this spot. The campground takes its name from nearby springs which emit strong gusts of cool air. The air comes from pockets and chambers that have developed in porous underground rocks.

At the northern end of Hidden Valley is Poor Farm, one of the most popular fishing, hunting, and primitive camping spots in the Warm Springs District. Where it flows through here, the Jackson River is regularly stocked with trout. Plenty of trails at both areas lead along the rivers and streams, up into gorges, over mountains and through fields and pastures in both areas. The well-packed and maintained trails are perfect for mountain biking, too. You won't find a better combination of good riding conditions, scenery, variety of topography, and lack of traffic than on the network of hiking trails and backroads here.

Hidden Valley Trail. [Fig. 26(22)] This streamside path follows the Jackson River 3.95 miles upriver. The first part of the trail is along the edge of a wide field with Cobbler Mountain in the background. Then the path leads into the woods where cool air from the Jackson feels refreshing on a hot summer day. A field guide will come in handy to help identify the many spring, summer, and fall wildflowers.

In late summer, look for the occasional yellow-fringed orchid (Habenaria ciliaris) in the open woods. This very showy orchid is leafy with a terminal cluster of yellow-orange blossoms with fringed petals. Other flowers along the trail include the cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), round-lobed hepatica (Hepatica americana), spring beauty (Claytonia virginica), and several varieties of trillium.

In one section of the trail, jutting rock ledges provide a contrasting backdrop to soft hemlocks. Sheltered woodlands where hemlocks grow usually have rhododendron and mountain laurel, and this river valley is no exception. The trail is the main link to an extensive network of hikes on Back Creek Mountain, Little Mountain, Cobbler Mountain, Warwick Mountain, Rocky Ridge, and Berry Knob. Look for well-marked trailheads at the Hidden Valley campground and across the Jackson River from Warwick Mansion.

Before the Hidden Valley Trail reaches the swinging bridge, a 1.2-mile trail to the right follows Muddy Run up a scenic gorge. At the bridge the 1.4-mile Jackson River Gorge Trail connects to the Hidden Valley Trail for a loop hike. At mile 1.7, a swinging bridge will take you across the river. Past the bridge, the trail is less heavily used. Special-regulation trout fishing is in effect on the Jackson River from the bridge for 3 miles upriver to the last ford on FR 481D. Artificial lures and single-hooks must be used. The creel limit is two fish of 16 inches or more per day. This section is stocked regularly several times a year with catchable-sized trout, and good populations are always present. Because the special-regulation section is accessible only by foot travel, anglers can expect solitude and good fishing.

Hidden Valley Trail. 3.95-mile linear path north along the Jackson River, providing connections to Bogan Run, Jackson River Gorge, Muddy Run, and, at its northern end, FR 241.

Bogan Run Trail. [Fig. 26(23)] For a real workout, take this link from the Hidden Valley Trail northwest across Back Creek Mountain. You'll pass Warwick Mansion, and then you'll enter a canopy of scarlet and chestnut oak as you climb 1,460 feet to cross Back Creek Mountain.

The trail ends on the west side near VA 600 on posted, private land. The Forest Service hopes to reroute the trail ending to allow vehicle access from VA 600. For now, however, hikers must backtrack to the starting point.

[Fig. 26(17)] The Bullpasture River is best known by anglers for its stocked trout. But the river and its environs delight everyone who drives the 12 scenic miles of VA 678 south of McDowell. In October, when trout stocking begins, a fly-fisherman or woman wading among the boulders and dancing waves is the perfect subject for a photograph. Red and yellow foliage of maples and poplars stand out on the mountainside in the background. The hemlock-lined banks are dark in the foreground. On the next cast, there's a distinct possibility a 4-pound rainbow just might add a bowed rod to the picture.

Several pullovers along the edge of the Highland Wildlife Management Area (WMA) provide access to fishermen, wildflower enthusiasts, birders, and photo-graphers. The WMA borders the river in the area of the gorge and just upriver from the gorge. The upriver portion is where most of the fishing, camping, and picnicking takes place. The public land here is one of three tracts that make up the 14,283 acres of the Highland Wildlife Management Area. This one is on Bullpasture Mountain which butts up against the northern end of Tower Hill Mountain to try to subdue the Bullpasture River as it passes between.

A second tract is on Jack Mountain southwest of McDowell. A small third tract is on Little Doe Hill about 2 miles west of McDowell and bordering the north side of US 250. The Jack Mountain tract has an 80-acre opening of bluegrass sod that was formerly used as summer pasture. This opening and several small wildlife clearings make good places to find wildlife, wildflowers, and butterflies. Vegetation at the edges of the clearings is especially attractive to animals. Bullpasture Mountain is best known for its deer and turkey populations. The more rugged Jack Mountain is known for its deer, turkey, and bear. Fair numbers of ruffed grouse, squirrels, and rabbits also live in these forests.

At the picnic area near Bullpasture Gorge, a swinging bridge spans the Bullpasture River. The woodlands on the other side are an ideal place to find wildflowers. Growing in the rich, sandy soil are red trillium (Trillium erectum), bluebell (Mertensia virginica), common blue violet (Viola papilionacea), and crested dwarf iris (Iris cristata), to mention a few.

Jack Mountain. [Fig. 26] From McDowell, go west on US 250 about 1.75 miles. Go left (south) on VA 615 and drive about 2 miles to area. Go right on Cobbs Hill Road or left on Buck Hill Road into Highland WMA. Buck Hill Road is gated except during hunting seasons.

[Fig. 26(7)] The people of Highland County say proudly that they have more sheep than people. Bluegrass Valley is a good place to make their case. "Valley" is a relative term. In Highland County, no place is low. At the center of the 18-mile-long Bluegrass Valley floor at High Town, where US 250 intersects VA 640, the elevation is over 3,000 feet. Snowy Mountain, to the northeast, rises to 4,500 feet.

Highland,

named for its mountains, has the highest mean elevation of any county in the

state. In fact, according to the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries,

the county is generally regarded as having the highest average elevation of

any county east of the Mississippi. No wonder it's sometimes called Little Switzerland.

A 50-mile east-west drive on US 250 is all that separates Bluegrass Valley from

the Shenandoah Valley town of Staunton and Interstate 81. Fifty miles would

be nothing on the arrow-straight interstate running north/south through the

Shenandoah Valley. But five mountain ranges lie between the Shenandoah Valley

and this remote outpost that's just a short hike from the state of West Virginia.

First, heading west from Staunton, there's Great North Mountain. Then Shenandoah

Mountain. Then Bullpasture and Jack mountains and finally the gap between Back

Creek and Monterey mountains. That's a lot of hairpin turns and two-lane road

between the two towns. But the isolation of Bluegrass Valley is what makes it

special.

Highland,

named for its mountains, has the highest mean elevation of any county in the

state. In fact, according to the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries,

the county is generally regarded as having the highest average elevation of

any county east of the Mississippi. No wonder it's sometimes called Little Switzerland.

A 50-mile east-west drive on US 250 is all that separates Bluegrass Valley from

the Shenandoah Valley town of Staunton and Interstate 81. Fifty miles would

be nothing on the arrow-straight interstate running north/south through the

Shenandoah Valley. But five mountain ranges lie between the Shenandoah Valley

and this remote outpost that's just a short hike from the state of West Virginia.

First, heading west from Staunton, there's Great North Mountain. Then Shenandoah

Mountain. Then Bullpasture and Jack mountains and finally the gap between Back

Creek and Monterey mountains. That's a lot of hairpin turns and two-lane road

between the two towns. But the isolation of Bluegrass Valley is what makes it

special.

This serene land between Back Creek and Lantz mountains seems a holdover from another time. Life is measured not so much with clocks and schedules but as a span between the planting of grain to the first rain. Time flows gently from one season to the next, measured as a color change from summer's lush greens to the bronze, crimson, and gold of fall to the browns and grays of winter.

VA 640, the single highway running through the narrow valley, is often devoid of a single car. Rising away from the road are highland pastures, climbing up the mountains on either side. In summer, sheep graze the steep hillsides above bottomlands of lush grain fields that move with the breeze. The low drone of bees in honeysuckle may be the only sound.

Golden-winged warblers have been spotted at beaver ponds located at the US 250 crossing of Back Creek just west of Hightown. Cedar waxwings, chestnut-sided warblers, and dark-eyed juncos are common summer breeders. In winter, a golden eagle may be spotted perched in a craggy tree. Twenty feet beneath the snag that holds the eagle is the object of interest—a healthy rainbow trout made sluggish by the cold. Bluegrass Valley is a wintering ground for the eagles, and local residents have become familiar with their presence. Rough-legged hawks are also winter residents.

The junction of US 250 and VA 640 at Hightown marks the separation between two watersheds. A turn onto VA 640 south follows tumbling Back Creek in the headwaters of the Jackson River. The Jackson will head for the James River and pass the state capital at Richmond on its way to the Chesapeake Bay.

Keeping VA 640 company to the north is a small stream with a responsible-sounding name—South Branch of the Potomac. The waters, which are stocked trout waters, are heading for the nation's capital at Washington, D.C., and then into the Chesapeake Bay. The land along the highway is private land. Wherever there are signs on trees indicating stocked waters, though, anglers may fish without landowner permission. In addition to a state fishing license, a trout license is needed October 1 through June 15 when stockings take place, but the trout license is not required during the rest of the year. Creel limit is six trout of 7 or more inches in length, although these regulations may vary from year to year.

[Fig. 26(2)] On a map, Virginia's western border resembles a torn piece of paper. One of those ragged edges is where the northern tip of Highland County reaches into West Virginia's Plateau country and borrows a slice of northern boreal forest. The forest gives Virginia 25 species of plants and animals found nowhere else in the state.

The area is called Laurel Fork, named after the high-altitude native trout stream flowing through the middle. Waters from this wild, remote mountain plateau will eventually join the Potomac River to flow past the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument at the nation's capital and then into the Chesapeake Bay.

The Nature Conservancy manages a 324-acre preserve at Laurel Fork. Most of this northern tip of Highland County, however, is part of the 10,000-acre Laurel Fork Special Management Area of the George Washington National Forest. The word "special" fits in more ways than one.

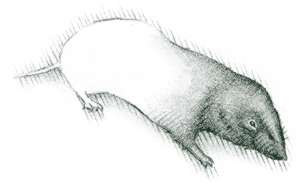

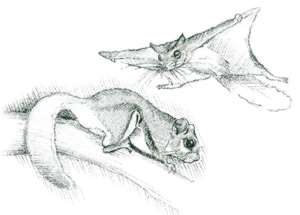

Laurel Fork—where plants and animals are more typical of coniferous forests far to the north—is the best example of the northern boreal forest complex in Virginia. Residents include such animals as the snowshoe hare, red squirrel, fisher, and red-breasted nuthatch. Here, the federally endangered northern flying squirrel builds dens in old woodpecker holes. Young squirrels must practice jumping and gliding from one tree limb to another to get the hang of it. As dusk turns to dark, the tiny novices may appear side-by-side on a limb outside a tree hole to begin practice.

Fishers

are usually found in New England and Canada. This relative of martens and wolverines

is one of the few animals that has figured out how to make a meal out of a porcupine.

At Laurel Fork, however, the fisher feeds on small mammals, carrion, birds,

fern tips, and fruits. Its fur is a beautiful dark brown to black with white

on the tips, giving it a frosted appearance. The red-breasted nuthatch creeps

head downward on tree trunks just as its larger cousin, the white-breasted nuthatch,

does. This coniferous-forest dweller smears the opening of its nesting cavity

with pitch. It can't help getting into the gooey mess itself, giving it an unkempt

look. Birds to look for also include the black-throated green warbler, golden-crowned

kinglet, and northern junco. Other species protected at the Special Management

Area include the Cheat Mountain salamander, southern water shrew, and a plant

called the hairy woodmint.

Fishers

are usually found in New England and Canada. This relative of martens and wolverines

is one of the few animals that has figured out how to make a meal out of a porcupine.

At Laurel Fork, however, the fisher feeds on small mammals, carrion, birds,

fern tips, and fruits. Its fur is a beautiful dark brown to black with white

on the tips, giving it a frosted appearance. The red-breasted nuthatch creeps

head downward on tree trunks just as its larger cousin, the white-breasted nuthatch,

does. This coniferous-forest dweller smears the opening of its nesting cavity

with pitch. It can't help getting into the gooey mess itself, giving it an unkempt

look. Birds to look for also include the black-throated green warbler, golden-crowned

kinglet, and northern junco. Other species protected at the Special Management

Area include the Cheat Mountain salamander, southern water shrew, and a plant

called the hairy woodmint.

Beavers—another common component of boreal forests—are capable of dramatically altering the landscape. True to form, the large rodents have dropped large trees in the drainages, creating shallow ponds and meadows that attract mink, muskrat, waterfowl, frogs, and salamanders. Moisture-loving grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs that spring from these beaver-created wetlands add an interesting mix to Laurel Fork. Beaver activity is mostly west of the Laurel Fork stream.

The unusual forest is a result of a complex combination of influences, including Laurel Fork's altitudes that vary from 2,600 to 4,100 feet. Elevation alone, however, is not enough. Another important factor is the area's position on what is called the Appalachian extension of the northern boreal forest—a connection to the great boreal forests across Canada, northern Europe, and Asia. The fingerlike extension reaches from northern North America down a narrow corridor of the Appalachians through Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and as far south as northern Georgia.

Boreal forests typically support a few dominant species. Across northern North America, entire sections of boreal forests may be comprised solely of balsam fir and white spruce. Along the Appalachian extension, though, red spruce grows in place of white spruce and Fraser fir replaces balsam fir. Firs and spruces may be told apart in a variety of ways. The needles on fir trees are flat while spruce needles are round. Also, the cones of fir trees stand up from the branches while the cones of spruce hang down. As boreal forests mature and the canopy grows denser, increasing darkness shades out the understory and leaves low-spreading shrubs or just mosses and ferns to carpet the floor. Decomposing needles form a soft mat underlain by highly acidic soil called gray spodosol. Boggy areas are common.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, Laurel Fork's trees were almost completely logged out before the land was purchased in 1922. Prior to logging, the forest was comprised of 40 percent spruce, 20 percent hemlock, and the remainder a mix of beech, birch, maple, oak, and cherry.

Although the percentage of evergreens is not as great as it was before logging, Laurel Fork still sustains a significant boreal forest but with a greater mix of northern hardwoods than it had in the original old-growth forest. Locust Springs Picnic Area [Fig. 26(1)] offers tables, an Adirondack shelter, water, and toilet facilities. Two hiking trails—Buck Run Trail and Locust Spring Run—lead southeast down drainages to the Laurel Fork Trail.

Hiking

at Laurel Fork. Many of the 28 miles of beautiful hiking trails in the area

make use of the old tram roads that were used to carry the trees out of the

forest. Despite the steep terrain of the area, the railroad grades provide easy

walking trails. The Laurel Fork Trail [Fig.

26(3)] is the main artery of the trail system. It follows the meandering

path of Laurel Fork southwest to northeast through the area, and other trails

branch off from it. Abundant pockets of rhododendron bloom along the trail in

June. Fly-fishermen pursue the secretive native brook trout that hide in quiet

pools of Laurel Fork. During periods of high water, Laurel Fork may be impossible

to cross.

Hiking

at Laurel Fork. Many of the 28 miles of beautiful hiking trails in the area

make use of the old tram roads that were used to carry the trees out of the

forest. Despite the steep terrain of the area, the railroad grades provide easy

walking trails. The Laurel Fork Trail [Fig.

26(3)] is the main artery of the trail system. It follows the meandering

path of Laurel Fork southwest to northeast through the area, and other trails

branch off from it. Abundant pockets of rhododendron bloom along the trail in

June. Fly-fishermen pursue the secretive native brook trout that hide in quiet

pools of Laurel Fork. During periods of high water, Laurel Fork may be impossible

to cross.

Other interesting trails include Buck Run, a 2.9-mile path from Locust Springs Picnic Area to the Laurel Fork Trail. Along the way are beaver ponds and fern, spruce, and cranberry bogs. Christian Run Trail [Fig. 26(4)] is a short, 1.5-mile (one-way) visit to old fields from pioneer homestead days. Bear Wallow Trail [Fig. 26(5)] is a 2.7-mile (one-way) trek to more beaver ponds and to openings with outstanding views.

All trails are blazed with blue paint. Maps of the trail system are available from the Warm Springs Ranger District office.

Laurel Fork Trail: 6-mile path (one-way) along Laurel Fork.

[Fig. 23(6)] In northern Rockbridge County, an easy hop from Interstate 64 is Goshen Pass and the Goshen—Little North Mountain Wildlife Management Area. Goshen Pass is a narrow sliver of gorge carved through the southern end of Little North Mountain by the Maury River. It assumes various personalities depending on the season. On summer afternoons, the laughter of children mingles with the shouts of college students from nearby Lexington's Virginia Military Institute or Washington & Lee University. In one way or another, everyone—including adults at picnic tables along the river's edge—is savoring a small spot of isolated beauty in northeastern Rockbridge County. The children splash and play in pools beneath apartment-size boulders. The college students squirt down long, slippery river boulders using inner tubes and belly slides. Everybody, including a fly-fisherman casting for stocked trout, stops to admire the skill of a kayaker shooting the rapids.

Goshen Pass, between Lexington and the town of Goshen, is only 100 yards wide in places and a short 7 miles long. The Maury River follows VA 39 through the popular gorge with its steep forested slopes and exposed cliffs and its several pull-offs for photography or fishing. This is a busy place on summer weekends.

Then in fall, when swimmers and picnickers are gone, orange-clad hunters spread out across adjoining Goshen—Little North Mountain Wildlife Management Area. The 33,697-acre wildlife management area, purchased through funds from hunting and fishing license sales, is managed by the state Department of Game and Inland Fisheries for deer, turkey, grouse, and squirrels. An occasional black bear also wanders through this largest wildlife management area in the state.

Goshen Pass and the rugged, beautiful Maury River divide the public lands of Goshen—Little North Mountain Wildlife Management Area into two large parcels. The parcels offer hunters, hikers, and mountain bikers a network of trails and roads leading to all parts of the wildlife management area. The area is maintained in a primitive state. There are no campgrounds or other facilities. Gated wildlife management area roads are open to foot travel year-round. Some are open to vehicular travel during hunting seasons.

Read and add comments about this page