Clinch

River Valley, Clinch Mountain, and North Fork of Holston

Clinch

River Valley, Clinch Mountain, and North Fork of Holston

Clinch

River Valley, Clinch Mountain, and North Fork of Holston

Clinch

River Valley, Clinch Mountain, and North Fork of Holston

The Clinch River gets its start near Tazewell, in Tazewell County. Helping it gain strength are many small tributaries draining steep hollows and ravines of coal country in the Appalachian Plateau of northwestern Tazewell County and northwestern Russell County.

Equally important, however, are the little streams and rivulets coming from the part of Tazewell County that's in the Valley and Ridge province—places such as the east slope of Burkes Garden, Thompson Valley, Paint Lick Mountain, and Knob Mountain. Born a hybrid—part Plateau coal country, part Valley and Ridge farming country—the Clinch then slows its pace. In Russell County, it comes into its own and begins the serious work of transporting to the Tennessee River the waters from northern Russell County, Scott County, and the southeastern slopes of Stone Mountain, Little Mountain, and Powell Mountain. South of Clinchport, in southern Scott County, Copper Creek adds clear, cold water to the Clinch from the eastern side of Copper Ridge and the western side of Moccasin Ridge.

Big

Moccasin Creek and Little Moccasin Creek [Fig.

12(18)] drain the east side of Moccasin Ridge and the west slope of Clinch

Mountain. The two creeks meet north of Gate City and cut through Clinch Mountain

at Moccasin Gap, to join the languid North Fork of the Holston on its way into

Tennessee and the Tennessee River.

Big

Moccasin Creek and Little Moccasin Creek [Fig.

12(18)] drain the east side of Moccasin Ridge and the west slope of Clinch

Mountain. The two creeks meet north of Gate City and cut through Clinch Mountain

at Moccasin Gap, to join the languid North Fork of the Holston on its way into

Tennessee and the Tennessee River.

Known primarily for its stocked muskie (Esox masquinongy), the Clinch

is

also gaining a reputation for its stocked walleye (Stizostedion vitreum).

Fish up to 9 pounds are showing up at scales. With an 11-inch to 14-inch slot

limit, the river is improving as a smallmouth fishery.

The Clinch is considered navigable from the town of Richlands in Tazewell County to the Virginia/Tennessee line in Scott County. Therefore, boating is legal in that stretch, and the river is becoming popular with float fishermen and canoeists. The uppermost access point is on VA 80 at Blackford in Russell County. Boats may also be put in at Cleveland, Carterton, and St. Paul in Russell County; at Dungannon, Clinch River, and Clinchport in Scott County; and from VA 727 just north of the Tennessee line. Two of the put-ins—Dungannon and Clinchport—have launch ramps.

A landmark of southwest Virginia is the stiff backbone of Clinch Mountain. It enters Virginia from Tennessee in western Scott County, turns east briefly, then takes off to the northwest. From Moccasin Gap at Gate City, the ridgeline rises to 3,020 feet and is unbroken for its entire march to Tazewell County.

Clinch Mountain curves around Brumley Mountain, which abruptly rises from the valley floor on the Washington/Russell county border. The once straight-as-an-arrow ridge also bends like an anvil around Laurel Bed Lake. But from Gate City northward, Clinch Mountain allows no breach and doesn't lose its identity until it bumps into the strange bowl of Garden Mountain some 90 miles to the northeast in Tazewell County.

North

Fork of the Holston River

North

Fork of the Holston River [Fig. 12] For its entire length in Virginia, Clinch Mountain has company. Starting as nothing more than a ditch in a Bland County field, the North Fork of the Holston River winds a sinewy path that roughly parallels Clinch Mountain all the way to Tennessee, as both river and mountain grow in strength.

Fishing the North Fork of the Holston. Smallmouth bass anglers are in heaven floating the quiet, green waters of the North Fork of the Holston. The river routinely produces smallmouth up to 5 pounds in weight. Channel catfish keep fishermen down on the river at night, lanterns glowing. However, mercury contamination from a salt-mining operation upriver at Saltville in the early 1970s still has the river under a health advisory. Fishing is allowed, but fish should not be eaten.

[Fig. 6] The upper Tennessee River system of southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee is, according to The Nature Conservancy, "one of the world's last great places." The private, nonprofit Conservancy has defined a 2,200-square-mile area across seven southwest Virginia counties and four northeast Tennessee counties as the Clinch Valley Bioreserve. Included are the watersheds of the Clinch, Powell, and Holston rivers, which form the headwaters of the major Tennessee River system. In Virginia, the boundaries stretch from Mount Rogers, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of eastern Smyth County, west to Cumberland Gap, where Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee meet. The defined area runs northeast into Tazewell and Bland counties to, but not including, Burkes Garden.

Such bioreserves contain outstanding examples of rare ecosystems, natural communities, and species deserving of protection. The focus differs from that of traditional nature preserves. Rather than attempting to protect endangered species at a specific site, the bioreserve has the broader goal of protecting an entire ecosystem.

In a bioreserve, the Conservancy identifies two areas: 1) core areas with habitat critical for rare species and 2) buffer areas, where water pollution, land development, invasion by non-native species, and other factors affect the health of the core area. Core areas may be set aside by traditional methods of purchasing land. In buffer areas, the Conservancy works in partnership with local people, businesses, governments, and agencies to meet human and economic needs while protecting fragile environmental areas such as watersheds.

The Virginia sections of the Clinch and Powell rivers are vital to the health of the Tennessee River system because the two rivers are the system's only undammed, unspoiled headwaters. Called "the most ecologically diverse region of Virginia," by the Conservancy, the river valleys contain more than 400 species of rare plants and animals, 22 of which are listed under the federal Endangered Species Act. The diversity is unmatched in the mid-Atlantic and northeastern United States.

Dependent on the swift waters of the Powell and Clinch are 16 species of rare fish such as the yellowfin madtom (Noturus flavipinnis), along with one of the world's richest concentrations of freshwater mussels. The number of mussel species identified here has dwindled from 60 to about 40. Of those, 26 are listed by the Conservancy as globally rare. At least 50 globally rare cave organisms, including beetles, spiders, flies, and other uncelebrated insects inhabit a network of some 1,250 caves beneath the rocky, porous surface of the bioreserve. The endangered gray bat, Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis), and Virginia big-eared bat hang from the ceilings of various caves. So far, landowners have voluntarily agreed to register 16 biologically significant caves for some level of protection.

Past industrial mercury contamination on the North Fork of the Holston and cattle farming along the Middle Fork have degraded the Holston River's waters significantly. The river is included in the bioreserve not because of its current diversity, but for its potential for recovery and for its importance as part of the Tennessee Valley watershed.

The Natural Heritage Division of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) performs an important first step in the establishment of such bioreserves with an intensive inventory of the region's most significant natural elements. Both state and federal game and fish agencies also assist, boosted with research by academic and amateur naturalists. To protect the bioreserve, the Conservancy must come up with creative solutions to degradation from agriculture, mining, and other economic mainstays of the region. An example is the effort to restore riparian (stream bank) damage done by grazing cattle. Unfortunately, cattle are rough on stream banks. When native vegetation is trampled, banks erode and sediment and animal wastes wash downstream. Water quality deteriorates and stream life is threatened. In mountainous areas, such as the headwaters for Copper Creek, swift running waters can erode unprotected streambanks quickly. In porous areas such as the Central Lee County Karst, contaminated water goes underground and flows downstream unfiltered and unpurified, finding its way into wells and rivers. Funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the DCR Division of Soil and Water Conservation enables the Conservancy to work with farmers to build fences to keep livestock out of rivers, find alternate water sources for cattle, and restore native vegetation to stream banks.

The Conservancy has acquired six preserves in core areas of the Clinch Valley Bioreserve. The first acquired (1983) was Pendleton Island, a 35-acre preserve on the Clinch River in central Scott County, a couple of miles southwest of Fort Blackmore. With 40 species of mussels in the waters around three wooded isles, this stretch is called the richest 300 yards of mussel diversity on the planet. It is illegal to pocket so much as a single mussel shell from these waters.

Since 1983, five more preserves have been purchased. Gray's Island Preserve, just outside Dungannon in northern Scott County, includes 300 acres of prime farmland and a stretch of the Clinch River with a significant mussel population. The Conservancy is selling farmland back to local farmers with restrictions to protect the river.

Four preserves, including one transferred to the state in 1997 as a Natural Area Preserve, are in the Central Lee County Karst. In the karst is the last intact cedar limestone glades community in Virginia—a key component of the bioreserve. The Conservancy also worked with Russell County officials and the state DCR to set aside a rugged 200-acre tract called The Pinnacle as another Natural Area Preserve, now administered by the DCR. (See Pinnacle Natural Area Preserve.)

[Fig. 6(7)] Before the Powell River leaves the state, it dawdles its way through a limestone seepage called the Central Lee County Karst. Karsts are characterized by porous limestone with deep fissures, sinkholes, underground caves, and streams. Because of the networking of underground water, any stream or river pollution can be devastating to fragile stream and cave life in the entire area.

A portion of the karst called The Cedars lies in a type of pavementlike limestone called Hurricane Bridge. This part of the Clinch Valley Bioreserve is about 3 miles wide and extends from Jonesville some 10 miles southwest to the Tennessee line. Shallow, drought-prone soil on the rocky ground creates an opening in the forest called a limestone glade where specialized plant and animal life survive.

Running glade clover (Trifolium calcaricum) was found in the limestone glade eight years ago. The only other site where it is known to exist in the world is 200 miles away in Tennessee. Producing creamy-white blossoms with wine-colored veins in May, the running glade clover resembles common white lawn clover, though it is not closely related. It has long, trailing stems, or stolons, which run along the ground and put down additional roots. The endangered herbaceous plant prefers thinly wooded to open areas, and has been located in 24 places over a 5-square-mile area.

The Lee County cave isopod (Lirceus usdagalun), an endangered crustacean resembling a grain of rice with legs, is found in two caves in The Cedars and nowhere else in the world. The tiny, eyeless, unpigmented troglobyte, or cave-dweller, kept plans for a federal prison and a county airport at bay for two years until the projects were moved to other sites.

As it flows through the glade area, the Powell River offers protection to the threatened spiny riversnail (Io fluvialis), and three threatened species of fish, each only inches long. These include the slender chub (Erimystax cahni), emerald shiner (Notropis atherinoides), and western sand darter (Ammocrypta clara). The Conservancy acquired the following four preserves with habitat critical to rare and endangered species in the karst area.

None is developed for public access at this time.

The

Cedars Natural Area Preserve [Fig.

6(8)], a 50-acre tract at the northern end of the karst, was first purchased

as a Nature Conservancy preserve in 1996. It was transferred by the Conservancy

to the state in 1997 to become a Natural Area Preserve. This purchase is a good

example of cooperation between agencies to protect such treasures. A bond referendum

passed by voters for the acquisition of natural areas and state parks is providing

the funds. Eventually, the Department of Conservation and Recreation which administers

the preserve will buy additional land for interpretive trails and public parking.

The

Cedars Natural Area Preserve [Fig.

6(8)], a 50-acre tract at the northern end of the karst, was first purchased

as a Nature Conservancy preserve in 1996. It was transferred by the Conservancy

to the state in 1997 to become a Natural Area Preserve. This purchase is a good

example of cooperation between agencies to protect such treasures. A bond referendum

passed by voters for the acquisition of natural areas and state parks is providing

the funds. Eventually, the Department of Conservation and Recreation which administers

the preserve will buy additional land for interpretive trails and public parking.

The scrubby, rocky barrens and glades of the state's newest Natural Area Preserve lie on the southern side of US 58 west of Jonesville. From a distance, the stand of red cedars, which often serve as a marker for limestone soil, may seem unremarkable. But the same poor, shallow soil in which the cedars thrive, along with a few Virginia pine and chinquapin oak, also supports 16 rare plant species and provides habitat for the loggerhead shrike (Lanium ludovicianus). Once common in Virginia, the shrike is rare to uncommon in the state and declining rapidly. Insects are the shrike's main diet, but it will eat small birds, mammals, and amphibians when insects are scarce. Lacking talons, the shrike is known for sometimes impaling its victim on thorny plants or barbed wire.

Unthanks Cave Preserve [Fig. 6(6)] is one of Virginia's largest and most biologically significant caves. It has an underground stream and 13 miles of mapped passageways that contain several rare cave organisms.

Powell River Bluffs Preserve [Fig. 6(9)] consists of towering limestone bluffs harboring rare plants such as false aloe (Manfreda virginica) and pitcher's stitchwort (Arenaria patula). The preserve is doubly valuable for its frontage on the most productive mussel shoals of the Powell River.

Beech Grove Cliffs Preserve [Fig. 6(10)] includes 100 acres of open woodland interspersed with limestone glades. Five rare plants grow on the cliffs above the panorama of the Powell River Valley.

Perhaps underrated as an outdoor activity, freshwater snorkeling is a wonderful way to cool off on a hot summer day while exploring the unfamiliar underwater world of mountain streams. Go to a sports or outfitting store. Spend at least $25 or $30 for a good mask that won't leak, and buy a snorkel. Locate a mountain stream or river that is fairly clear. Where highway bridges cross the water, public rights-of-way allow legal access. If the river is considered navigable, the entire riverbed is public land, so you can wade upriver or downriver without getting on someone's private property. Pick a place where the current is not too swift and the water no deeper than your arms are long. Wade out into the current, face upstream, and lie face down in the water, letting it support your body while you breathe through the snorkel. Use your hands on the bottom to pull yourself along. You'll be amazed at what you find.

Snorkeling will open a window to the fascinating life in the stream and among the rocks on the bottom. Some rocks may be covered with several varieties of snails. Various freshwater mussels may line the bottom. Minnows will rest in the eddies on the downstream side of rocks and boulders. A crayfish may pump itself backward from you with its powerful tail. Before long, you'll find yourself in a bookstore, looking for field guides to identify the plant life and critters that inhabit a stream. Snorkeling is a perfect outlet for a child's energy and natural curiosity. The importance of protecting streams from pollution and siltation will be obvious when they see firsthand how a mussel feeds.

Before you take any mussels home for a meal, check local restrictions. Collecting rare or endangered mussels from the Tennessee Valley watershed is illegal. Game wardens will not hesitate to ticket anyone violating the law.

Natural

Tunnel State Park

Natural

Tunnel State Park [Fig. 16, Fig. 12(13), Fig. 13(16)] When William Jennings Bryan stood on a high cliff above Natural Tunnel more than 100 years ago, he declared in his finest stentorian voice that the 850-foot-long tunnel, carved by a cascading stream though limestone and dolomitic bedrock, ought to qualify as "the eighth wonder of the world."

More than 100 years earlier, Daniel Boone also came upon Natural Tunnel while scouting a route for his Wilderness Road to the frontier lands west of the Allegheny Mountains. But Boone, an unlettered and pragmatic man, left no Bryanesque pronouncements. Boone was looking for passes, or gaps, through the mountains, not evidence of a million years of natural water erosion and geologic plate grinding, impressive though such evidence might be.

Natural Tunnel today is the centerpiece of Virginia's Natural Tunnel State Park. Though half hidden in the rugged mountain folds of southwest Virginia in Scott County, the tunnel and its surroundings have stirred the imaginations of naturalists, geologists, and other visitors since the area was first visited and described by Lt. Col. Stephen H. Long in 1831. The 850-acre park surrounding Natural Tunnel today is designed to help visitors savor the relentless power of natural forces. Seven hiking trails, some with breathtaking views, crisscross the area. A modern, suspended chair ride, similar to a ski lift, does away with the need for a 530-foot climb down a foot trail to the tunnel entrance. The chair lift and observation deck above Stock Creek, which helped carve the tunnel from surrounding limestone, also accommodate the handicapped. Watch as many as 20 Norfolk Southern trains rumble through Natural Tunnel daily, still hauling coal to power plants of the Southeast.

In

spring, a variety of wildflowers such as columbine (Aquilegia canadensis),

jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaematriphyllum), and fire pink (Silene virginica)

bloom throughout the park. American beech (Fagus grandiolia) and tulip

poplar shade the forest floor in summer. Autumn is a blaze of color as hardwoods

turn rust, red, yellow, and gold. Canby's mountain lover (Pachistima canbyi),

a rare wildflower, grows on the park grounds.

In

spring, a variety of wildflowers such as columbine (Aquilegia canadensis),

jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaematriphyllum), and fire pink (Silene virginica)

bloom throughout the park. American beech (Fagus grandiolia) and tulip

poplar shade the forest floor in summer. Autumn is a blaze of color as hardwoods

turn rust, red, yellow, and gold. Canby's mountain lover (Pachistima canbyi),

a rare wildflower, grows on the park grounds.

Natural Tunnel State Park is also one of the premier karst areas of the state, according to Craig Seaver, park manager. An untold number of holes, caves, and underground caverns lie in the sedimentary carbonate dolostone (similar to limestone, but with a magnesium component) and siliciclastic (comprised mostly of clay and quartz) rocks in the area. Even on the drive to the park from Gate City along US 23, road cuts have exposed fault lines and layers of twisted rock that were once an ocean floor. Seaver compares the mounded shape of some rocks to the appearance of sand mounded up on a beach by wave action.

The park vicinity is pocked with sink holes. A sink hole is a circular hole, from a couple of feet to a mile across, where an underground cavern has collapsed. Residents of the area used to try to fill these "sinks" with everything from garbage to junk cars until they learned they were despoiling their own springs, wells, and water supplies. A new hiking trail will soon lead to a sink hole at Rye Cove at the park's upper end.

Interpreting the area's natural history is a focus of guided hikes and tours to the mouth of the tunnel for a firsthand look at how an underground river can sculpt solid rock over hundreds of thousands of years. The stratified rock of Natural Tunnel belongs to what is called the Knox group (named for rock first exposed at Knoxville, Tennessee). It was laid down during the early Paleozoic Era, during the Ordovician and Cambrian periods. The Knox group carbonates contain fossils of algae that were plentiful 500 million years ago—some 270 million years before dinosaurs walked the earth.

The tunnel was once thought to be the uncollapsed remains of a large cave system. Modern geologic evidence, however, does not support this theory. The tunnel and creek are positioned along what is called the Glenita fault, a zone of structural weakness between the gently folded Rye Cove syncline, or downfold, on the east, and the more tightly folded Purchase Ridge syncline to the southwest.

The Glenita fault is evident a few feet above the north opening into the tunnel, and it is visible to the west and south through the wooded bluffs between the tunnel and VA 871. Because of the many fractures along the fault zone, circulating ground waters are better able to dissolve the deformed rocks. The gradual erosion (wearing away) and solution (dissolving) of rock that resulted in the formation of Natural Tunnel is a long and complex process. Geologists with the Virginia Division of Mineral Resources now believe a large sink developed in the ground above the present tunnel near the north portal. The waters of Stock Creek seeped from above into the sink, descending underground to about the current level of the creek. The water then flowed southward and rose from the depths to emerge as a spring near the south portal. Because the rock strata happened to be relatively horizontal here, it could support the great weight of the span that developed.

As the sink gradually grew larger, the cascading waters of Stock Creek, laced with abrasive grains of quartz sand and gravel, carved a steep valley below the tunnel. Visitors today can witness the spectacular result—a semicircular amphitheater, comprised almost entirely of sedimentary carbonate rock, that towers above Stock Creek. The park also has a 2,000-seat, man-made amphitheater, which is the setting not only for programs about the park, but for traveling troupes and entertainment groups as well.

Wild caving is another new offering at Natural Tunnel. Visitors with a thirst for adventure can don hard hats, coveralls, boots, and head lamps such as those used by miners. Park naturalists lead the way beneath the surface to a limestone cave with stalactites and stalagmites.

The modern visitor center [Fig. 16(11)] houses wildlife displays, exhibits on the formation of Natural Tunnel, samples of fossilized marine life from the tunnel walls, and relics from the early days of the tunnel railroad.

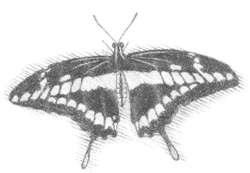

Butterfly Garden of Natural Tunnel State Park. [Fig. 12(14), Fig. 16(10)] Sweet smells wafting by visitors' noses at Natural Tunnel are likely from the butterfly garden started in 1996. Guests may follow their noses—or perhaps a spicebush swallowtail—to the colorful area at the end of the parking lot adjacent to the visitor center. There, the southwest Virginia Master Gardeners surprise even the park superintendent with the success of the flowers they planted to attract butterflies. Among the 35 varieties are sweet alyssum (Lobularia), butterfly-weed (Asclepias), blanket flower (Giallardia), larkspur (Delphinium), day-lily (Hemerocallis), bee-balm (Monarda), catnip (Nepeta), and lavender (Lavandula).

Volunteer groups such as the Master Gardeners are responsible for a great deal of landscaping, trail building and clearing, and other work at Virginia's state parks.

Hiking Trails of Natural Tunnel State Park. The park's seven trails are not long, but by interconnecting them, hikers can manage a 3- or 4-mile hike with several views of the tunnel and precipitous gorge. The trails have been improved with paved walkways, railings, steps, and benches.

Five trails are basically level, as mountain trails go. The Purchase Ridge Trail [Fig. 12(15), Fig. 16(13)] however, climbs 1.1 miles to 2,200 feet, the park's highest point. The climb is strenuous at times, but the reward is a scenic overlook of the tunnel from afar. The .3-mile Tunnel Trail [Fig. 12(16), Fig. 16(4)] is easy as it leads down into the gorge for a close view. However, if the tunnel doesn't take guests' breath away, the short but steep climb back up will. The .4-mile Lover's Leap Trail [Fig. 12(17), Fig. 16(9)] has an accompanying brochure to guide you through the area's history as you walk the woods above the tunnel.

[Fig. 12(9)] This place is a naturalist's dream. It has a little bit of everything. Towering above Big Cedar Creek are dramatic cliffs and ledges. As background music to the drilling of a pileated woodpecker, the creek glides across gentle riffles, hesitates in smooth pools, and tumbles over an impressive cascade as it searches out the Clinch River.

The

200 acres of Pinnacle Natural Area Preserve are home to a rich assortment of

natural communities—cove woodlands, riverine plants, limestone cliff vegetation,

ridgetop glades, and high-gradient streams. Nine rare animal species and 12

rare plants have been identified at the preserve. The paths you walk at the

Pinnacle very likely were the same paths walked by Indians who once lived here,

say archeologists.

The

200 acres of Pinnacle Natural Area Preserve are home to a rich assortment of

natural communities—cove woodlands, riverine plants, limestone cliff vegetation,

ridgetop glades, and high-gradient streams. Nine rare animal species and 12

rare plants have been identified at the preserve. The paths you walk at the

Pinnacle very likely were the same paths walked by Indians who once lived here,

say archeologists.

The Pinnacle was formerly managed by Russell County as Big Cedar Creek Park. Recognizing the fragile nature of the area, county supervisors conveyed the property to The Nature Conservancy in 1989 for temporary protection until the site was taken into the state's system of natural area preserves. It is now managed by the Department of Conservation and Recreation as a satellite of Hungry Mother State Park. The DCR has recently acquired more land surrounding the Pinnacle to allow for recreation and to provide a buffer to the preserve's more sensitive areas.

The calcium-rich bedrock of Pinnacle Natural Area Preserve has eroded to produce fertile soils on slopes below dolomite and limestone ledges. The presence in the soil of magnesium, the component in dolomite that differentiates it from limestone, has a subtle though significant effect on the vegetation. Unusual ferns and wildflowers—the kind you won't find in most identification books—thrive in these conditions. Smooth cliff-brake (Pellaea atropurpurea), northern prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum), and Carey's saxifrage (Saxifraga careyana) are among the varieties. Saxifrage, a relative of the rose family, is a plant of cool mountains and rocky places. Its leaves often form a rosette or cluster at the base. Dolomite glades such as the one at the Pinnacle usually grow on steep, south-facing slopes, and frequently contain one or more globally rare plant species. The federally endangered glade spurge (Euphorbia sp.) and Canby's mountain lover grow here.

The waters of Big Cedar Creek, which drain the northwest slope of Clinch Mountain Wildlife Management Area and part of Moccasin Ridge, are cold enough to support a trout fishery and are in the state's regular trout stocking program. Beneath the creek surface, however, lies magic beyond beautiful trout. This relatively pristine stream makes its own contribution to the rare mussels of the Clinch and other southwest Virginia rivers that are part of the upper Tennessee River drainage.

The endangered birdwing pearlymussel (Lemiox rimosus) dwells in shallow riffles of fast-flowing streams such as this one. The impact of coal mining on water quality and the invasion of foreign zebra mussels threaten its existence, even here. This mollusk grows to about 2 inches long and has a dark green outer shell.

With a mask and snorkel, a person wading Big Cedar can peek beneath the surface for a possible encounter with the locally rare spiny soft-shell turtle (Trionyx spiniferus), the globally rare spiny riversnail, or the hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis). At 18 inches long, the hellbender is one of the largest salamanders in the world. Though it would never win a beauty contest, this resident of clear Appalachian streams is harmless to man. Fishermen may occasionally curse it for stealing bait, but the hellbender feeds mainly on crayfish.

A foraging skunk may nose into a rotten log to send the Big Cedar Creek millipede (Brachoria falcifera) scurrying for cover. Unlike centipedes, which have one pair of legs on each body segment, the slower-moving and smaller millipedes have two pairs of legs on each segment. If the skunk is quick enough, he'll have this globally rare millipede for lunch. Protection of rare and endangered species is of prime importance at Pinnacle Natural Area Preserve. Stay on trails and keep pets on a leash to avoid damaging fragile wildflowers and plants. All plant and wildlife species here are protected by law and should not be disturbed.

Be careful of slippery rocks, especially around waterfalls. Diving in unfamiliar water is very dangerous.

Hiking Trails at Pinnacle Natural Area Preserve. [Fig. 12(9)] Since protection of rare communities of plants and animals is the focus here, trails have not been a priority. However, a network of nameless trails was built by the Young Adult Conservation Corps in 1978. The trails run along the banks of Big Cedar Creek and the Clinch River and climb to a scenic overlook atop Copper Ridge, where there is a view of the Pinnacle and below, the stream.

As hikers ascend, they will pass through a ridgetop glade community of rare, fragile plants with unusual names such as American harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), tufted hair grass (Deschampsia caespitosa), Canby's mountain lover, and white camas (Zigadenus glaucus).

[Fig. 12(19)] Tucked into the shadow of Clinch Mountain at Hiltons is a rustic building called the Carter Fold, where old-time acoustic mountain music still rings down the hollows every Saturday night. The weekly event is sponsored by the family of Mother Maybelle Carter and June Carter Cash of country music fame. Shows begin at 7:30 p.m.

[Fig. 12(1)] Discovering a forest-green fishing lake atop steep and wild Brumley Mountain is akin to finding an emerald in a haystack. Brumley abruptly rises from the valley floor, interrupting the northwest/southeast line cut by Clinch Mountain. On the mountain's flat top, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries manages 6,400 acres for wildlife. Brumley Creek has been dammed in narrow Hidden Valley to form a high-country lake that harbors walleye, smallmouth bass, rock bass, and bluegill. A boat ramp on the north side provides access, but the open banks make casting easy for the angler without a boat.

Area fishermen and hunters use the area, but largely undiscovered is its potential as a place to watch wildlife, identify songbirds, and photograph spectacular scenery in a setting far from the crowds that prefer more developed areas. Migrating hawks and other birds of prey sometimes settle in the protected high valley overnight, but fall-migrating, southbound birds of prey are more visible at Clinch Mountain Wildlife Management Area 25 miles to the northeast (see Clinch Mountain Wildlife Management Area).

Visitors should wear blaze orange during fall or winter hunting seasons and bring clothes suitable to the cooler temperatures and unpredictable weather changes of high elevations. Elevations at Hidden Valley exceed 4,000 feet. Topo maps and a compass are helpful when exploring the estimated 10 miles of trails in the unmarked backcountry. Two of the more popular trails lead out of the parking lot at the Wildlife Management Area (WMA) entrance. They provide panoramic views of the Clinch Mountain ridge to the southeast. No developed campgrounds are available, but camping is allowed throughout the forest, as long as campsites are 100 yards away from the lake. Stays are limited to 14 consecutive days.

The cover of mixed hardwoods, including white and red oaks, yellow birch, American beech, and hickory is home to white-tailed deer, black bear, wild turkey, ruffed grouse, gray squirrel, and cottontail rabbit. Hunters should check the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries for regulations, which change yearly, and may vary from those of surrounding Washington County.

Evergreen hemlocks and rhododendron thickets shade the moist, deep ravines and hang over the lake on the south side. In places, including a patch along the road on the far end of the lake, just before you get to the dam, the rhododendrons have grown quite large. Profuse running cedar adds its own carpet of green throughout the year. Ducks and waterfowl are attracted to the boggy upper end of the lake where aquatic vegetation and stumps of flooded trees offer food and cover. Beaver sign is often visible here, too.

Getting from Hidden Valley Wildlife Management Area (WMA) to Clinch Mountain WMA has its own rewards.

Take VA 689, VA 80, and VA 613 through Poor Valley, which lies on the southeastern flank of Clinch Mountain and is separated from Rich Valley (to the south) by Little Mountain. The pleasant drive through this tiny, picturesque valley follows the West Fork then the East Fork of Wolf Creek.

Parallel backroads on the south side of Little Mountain (VA 611, then VA 91 and VA 42) in the Holston River watershed are also recommended. None is an official scenic byway. Maybe the valley was too pretty to pick just one.

Clinch

Mountain Wildlife Management Area

Clinch

Mountain Wildlife Management Area [Fig. 17(1)] Clinch Mountain Wildlife Management Area (WMA), the second largest WMA in Virginia, is also the state's most biologically diverse. The steep rise from the valley floor at 1,600 feet to the highest peak of 4,700 feet is the primary reason for the diversity. At lower elevations, southern hardwoods—trees more typical of north Georgia—prevail, along with related bird and animal life. These trees include white oak, American beech, sweet gum, black gum, sourwood, and various hickories. At higher elevations, look for the peeling, pale-yellow bark of abundant yellow birch. Also, there's Eastern hemlock, sugar maple (which turns bright red in fall), American beech, pitch pine, table mountain pine, Virginia pine, and northern red oak.

Four counties—Washington, Russell, Tazewell, and Smyth—lay claim to parts of the WMA's 25,477 acres. The entrance road on Short Mountain along Big Tumbling Creek lies in the northern tip of Washington County. Big Tumbling Creek, two smaller creeks, and Laurel Bed Lake are popular with area anglers for good reason. During a fee-fishing season, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (VDGIF) stocks them daily (except Sunday) with hatchery-raised trout. Fishing permits are on sale at the concession stand on the entrance road.

Fisherman cast nightcrawlers, meal worms, flies, or spinners for trout along these canopied streambanks, where icy water cascades over ledges and forms clear pools. Big Tumbling Creek is a tempting place to pull over on a warm spring afternoon and introduce a youngster to the pleasures of wading a cold stream in pursuit of the colorful rainbow trout.

Northeast of the entrance road, in Russell County, Clinch Mountain has a butterfly-shaped plateau called Beartown Mountain. At 4,700 feet, Beartown is the WMA's highest point, rising more than 3,000 feet above the valley floor. Southern hardwoods give way to northern hardwoods here, even patches of red spruce. The picturesque evergreen with its ragged dark green spires is a favorite subject in paintings of alpine meadows. On a lower plateau, to the east of Beartown and still in Russell County, the waters of Laurel Bed Creek have been dammed to form 300-acre Laurel Bed Lake. Although more than 1,000 feet lower than Beartown Mountain, the lake is plenty high enough to be suitable temporary cold-water habitat for the brook trout that are stocked. The season extends from mid-March to Labor Day, but the fishing is best in spring, when limits of six trout are common.

Like many mountain lakes and streams, the waters of Laurel Bed Lake gradually became too acidic to support trout on a long-term basis. In 1996, biologists worked to raise the pH levels with a liming project, which included using a helicopter to place limestone sand into the stream above the lake. After restoring the proper balance, biologists continue to stock catchable-size trout for current seasons. In addition, they are stocking fingerling brook trout in the lake each year (beginning in fall of 1997). The biologists hope the fish will feed naturally on lake forage and grow to trophy size, returning Laurel Bed to the premier fishery it was in the past.

Gasoline motors are not allowed, but a big-muscled bass boat would be an overstatement on quiet Laurel Bed Lake anyway. There are two launch ramps for putting in canoes, kayaks, or john boats for a quiet paddle along the shoreline.

Visitors may have to throw a branch out of the trail or climb over a fallen tree now and then to hike the narrow footpaths of the rugged mountain country. Old logging roads and a narrow gauge railroad bed also provide good access to hunters, hikers, mountain bikers, and horseback riders. Hikes may lead visitors into the backcountry of Tazewell or Smyth counties. By their very nature, WMAs are more primitive than state parks, but they offer a fine place to see a variety of habitats and wildlife. A topo map and compass are helpful guides in this undeveloped country.

Black bear, white-tailed deer, wild turkey, gray squirrel, cottontail rabbit, ruffed grouse, groundhog, raccoon, waterfowl, and nongame species as well, benefit from the state's management activities at Clinch Mountain. These management activities include mowing and burning over 500 acres of clearings and trails; planting shrubs to provide edge cover; thinning thick growths of trees and shrubs to allow food-producing types such as oak, apple, thornapple, and walnut to grow; planting strips of native warm-season grasses; and regenerating forests through firewood cuttings and saw timber harvest.

Beavers

have cut trees in many places, damming creeks and opening the forest canopy

to increased sunlight. The creation of ponds and wetlands has attracted aquatic

wildlife such as waterfowl, muskrats, frogs, turtles, water snakes, and the

animals that prey on them. Rushes, sedges, and shrubby growth have replaced

the hardwoods. Fifty wood duck nesting boxes are maintained by the Virginia

Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Plans include an ambitious bluebird

box program and the refurbishing of tree swallow houses along Laurel Bed Lake.

Beavers

have cut trees in many places, damming creeks and opening the forest canopy

to increased sunlight. The creation of ponds and wetlands has attracted aquatic

wildlife such as waterfowl, muskrats, frogs, turtles, water snakes, and the

animals that prey on them. Rushes, sedges, and shrubby growth have replaced

the hardwoods. Fifty wood duck nesting boxes are maintained by the Virginia

Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Plans include an ambitious bluebird

box program and the refurbishing of tree swallow houses along Laurel Bed Lake.

The tree swallow (Iridoprocne bicolor) has an unusual habit that resembles play. The agile bird with blue-green back, forked tail, and white underparts seems to enjoy carrying a feather into the air, dropping it, and diving to catch it as it falls. The great blue heron and solitary sandpiper fish the shallows. Pied-billed grebes, black ducks, and buffleheads may stop to restock the larder on their fall migrations.

Read and add comments about this page