Joyce

Kilmer–Slickrock Wilderness Area

Joyce

Kilmer–Slickrock Wilderness Area  Joyce

Kilmer–Slickrock Wilderness Area

Joyce

Kilmer–Slickrock Wilderness Area [Fig. 37(38), Fig. 38] Joyce Kilmer–Slickrock was designated a wilderness area with the passage of the 1975 Wilderness Act. Nine years later, when the 1984 North Carolina Wilderness Act went into effect, the original 14,033 acres increased to the present 17,013 acres. Joyce Kilmer–Slickrock shares a common boundary along the Unicoi Mountains with the Citico Creek Wilderness in the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee. Portions of the Joyce Kilmer–Slickrock Wilderness Area are actually in the Cherokee National Forest, although the majority of its lands are in the Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina.

The two dominant watersheds in the wilderness area are the Little Santeetlah Creek and Slickrock Creek, which are joined by a common ridgeline at their head-waters. Their basins are steep and rugged, with elevations ranging from only 1,086 feet at the mouth of Slickrock Creek to 5,341 feet on Stratton Bald. Rock outcrops are common, and a network of streams dissect the terrain. Only in the higher ridges do heath or grass balds break the dense hardwood forests that blanket the slopes.

The shining star of this wilderness area is the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest—the kind of place that brings out the poet in all of us. The 3,840-acre preserve was named after the poet who wrote the poem "Trees," although Kilmer never saw the virgin poplar and hemlocks here that have graced the earth for 400 years, some reaching 150 feet in height and 20 feet in circumference. Inside their sheltered canopy, the atmosphere is decidedly different from other forests. It is quieter, the birds so high in the treetops that their songs are hard to hear. The understory is markedly different, too, not nearly so lush or overwhelming as in second-growth forests still evolving. To say the forest is like a cathedral is no literary excess—its majesty and peacefulness create an other-worldly atmosphere. Tall trees form columns and arches that seem to draw thoughts and energy skyward. A soft carpet of bright green moss and multihued lichens soften our earthbound existence.

Much

of the surrounding land in the region was logged by timber companies. Babcock

Land and Timber Company, which logged the surrounding Slickrock Creek area,

owned the Little Santeetlah Creek basin that forms the Joyce Kilmer Memorial

Forest. Over the years, other timber companies have held the deed, yet, for

a variety of reasons, they never logged it.

Much

of the surrounding land in the region was logged by timber companies. Babcock

Land and Timber Company, which logged the surrounding Slickrock Creek area,

owned the Little Santeetlah Creek basin that forms the Joyce Kilmer Memorial

Forest. Over the years, other timber companies have held the deed, yet, for

a variety of reasons, they never logged it.

Officially, the memorial forest was saved from destruction in 1936 after a long series of seemingly unrelated events that ranged from bankruptcy and bravery to warfare and the welfare of a small mountain river basin. Alfred Joyce Kilmer wrote his now-famous poem "Trees" in honor of a magnificent white oak tree on the campus of Rutgers College in New Jersey, where he attended school from 1904 to 1906. He eventually became an editor at the New York Times and continued to write and publish his poetry. "Trees" was first published in his second book of poetry in 1914, the year that World War I began. In 1917, when the United States entered the war, Kilmer enlisted and went to France, where, on July 30, 1918, he was killed during a reconnaissance mission. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre for his bravery.

The brave yet gentle spirit of Kilmer was not easily forgotten. In 1934, a New York chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars petitioned the federal government to find an appropriate memorial for Kilmer. The government agreed and asked the U.S. Forest Service to locate a tract of virgin forest in the eastern United States—not an easy task given the unregulated logging the mountains had suffered. By chance the forest in the Little Santeetlah basin had been spared. A series of odd circumstances contributed to its survival, such as the construction of two lakes—Calderwood and Santeetlah—that flooded the rail system necessary for transporting the timber out of the region and the bankruptcy of a logging company just before it was ready to use its recently constructed splash dams to float out the trees. Finally, the U.S. Forest Service purchased 13,055 acres in the Little Santeetlah basin from Gennett Lumber Company in 1935 for $28 an acre—an exorbitant price at a time when most land was selling for only $4 an acre. But it was worth it, and the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest was dedicated on July 30, 1936, 18 years to the day after the poet's death. In 1975, Congress designated the Joyce Kilmer–Slickrock Wilderness, which included the memorial forest.

The Joyce Kilmer National Recreation Trail [Fig. 38(11)] is an easy 2-mile trek through the forest along two loops: the 1.25-mile lower loop and the .75-mile upper loop coursing through Poplar Cove, a rich, fertile grove hosting the largest trees in the forest. The two loops converge at the Joyce Kilmer Memorial [Fig. 38(13), Fig. 39(1)], a large boulder with a plaque to the fallen soldier-poet. In spring, before the canopy filters out the sunlight, wildflowers are abundant along the pathways. A variety of violets, trilliums (of proportions as impressive as the trees), solomon's seal (Polygonatum biflorum), galax (Galax aphylla), crested dwarf iris (Iris cristata), jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), and carpets of ferns fill the understory.

In addition to the mighty yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) and Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), the forest harbors red oak (Quercus rubra), basswood (Tilia americana), red maple (Acer rubrum), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), yellow birch (Betula lutea), Carolina silverbell (Halesia carolina), dogwood (Cornus florida), and witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), among others. Birds are hard to spot in these tall treetops, but the songs of the downy woodpecker (Dendrocopos pubsecens), wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), solitary and red-eyed vireo (Vireo solitarius and Vireo flavoviridis), ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapillus), golden-crowned kinglet (Regulus satrapa), scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea), and brown creeper (Certhia familiaris) have been reported.

Never

is the sound of water far away, either—the rushing Little Santeetlah closer

to the trailhead or the trickling tributaries on their way toward bigger waters.

While the trail is only 2 miles in length, the walk takes much longer than average

because there is so much to see along the way. (And the frequent craning to

see mighty treetops has caused more than a few stiff necks!) Even the dead and

down trees are like magnificent sculpture, coming to life again with a host

of mosses, lichens, fungi, and wildflowers growing in their decaying mass.

Never

is the sound of water far away, either—the rushing Little Santeetlah closer

to the trailhead or the trickling tributaries on their way toward bigger waters.

While the trail is only 2 miles in length, the walk takes much longer than average

because there is so much to see along the way. (And the frequent craning to

see mighty treetops has caused more than a few stiff necks!) Even the dead and

down trees are like magnificent sculpture, coming to life again with a host

of mosses, lichens, fungi, and wildflowers growing in their decaying mass.

Because the forest is in a designated wilderness, dead or dying trees are not removed. Sadly, some of the huge trees are dying, which increases the potential for falling limbs and trees. A large sign at the trailhead cautions against walking here on windy days or after a snowfall or ice storm when branches and trees are more likely to fall. Also watch out for hunters. Hunting and fishing are popular in the memorial forest and the Slickrock Wilderness, especially bear and boar hunting from mid-October until the end of the year (except for two weeks in late November and early December set aside for deer season).

The trail network within the entire Slickrock Wilderness Area offers more than 60 miles of trails carefully laid out to allow access to the many topographic regions within the wilderness, such as rock outcrops; rich, moist coves; virgin and old- growth forests; boulder-strewn creeks; and grass and heath balds. The trails also were designed to interconnect and, therefore, allow extended hikes through the wilderness. Because this is a wilderness area, with the exception of the paths at Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, the trails are primitive, rugged, and virtually unmarked. Some are easy to follow or are used enough to make the pathway obvious. Others, however, are more difficult, and like any wilderness experience, they require a topographic map and compass.

Wilderness areas are often associated with serenity and solitude. As interest in this area grows, however, some trails and sections are more popular than others. According to the Joyce Kilmer–Slickrock map from the U.S. Forest Service, the trails within the wilderness that offer the least opportunity for solitude include Joyce Kilmer National Recreation Trail, Naked Ground [Fig. 38(7)], Big Fat Gap [Fig. 38(3)], Hanover Lead [Fig. 38(4)], Slickrock Creek [Fig. 38(1)], Stiffknee Trail [Fig. 38(2)], and Falls Branch Falls Trail. Stratton Bald, on the other hand, offers a journey into virgin forest on a quiet and peaceful trail. The trailhead is found easily just across the Santeetlah Creek from the Rattler Ford Group Campground near Joyce Kilmer. Though it is rated "most difficult," other than a few rocky segments, it is a moderate, easy trail into a pristine virgin forest.

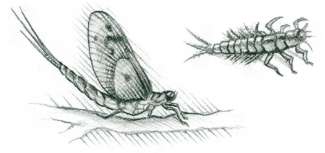

Bears and wild boars populate the wilderness and adjoining national forest. The wild boars (Sus scrosa), or "hogs," as they are referred to locally, were first introduced to the region in 1912, when 13 were imported to a private game preserve below Hooper Bald. Ox-drawn wagons carried the boars to their new home along with a number of buffalo, elk, mule deer, bears, wild turkeys, and thousands of ring-necked pheasant eggs. Eight years later, 100 boars escaped the confines of the preserve and over the years have multiplied into a growing problem. They are a hardy species, learning, adapting, and breeding quickly. A 125-pound boar can eat as much as 1,300 pounds of food in a six-month period, which, given the way they forage for food, tears up vast amounts of ground and disrupts plants and soil. This foraging in turn destroys groundcover and habitats and causes erosion and siltation. Boars thrive in all types of elevations and forests and as omnivores, on all kinds of food. Though they favor nuts, they will eat insects, salamanders, eggs, and small mammals, as well as wild yams and bulbs and roots of wildflowers.

As the hogs' numbers have grown, so have efforts to control them. In the nearby Great Smoky Mountains National Park, hunting, trapping, fencing, and luring have been tried with differing degrees of success and popularity. Some boars have been relocated from the park to the national forests, where they can be hunted. The efforts are ongoing as rangers at the national forest and Great Smoky Mountains National Park work toward a balanced solution.

Just outside the wilderness area in the Nantahala National Forest, Maple Springs Observation Area [Fig. 38(5)] offers a spectacular 180-degree view of the surrounding mountains. An easy 5-mile drive north of Joyce Kilmer on SR 1127, this is literally a road to nowhere. It began as part of the road first envisioned in the 1950s that today is known as Cherohala Highway. Construction began in 1965, but when the area was designated as wilderness, the road had to be rerouted along the Unicoi Crest. As a result, this earlier road now ends at the Maple Springs parking area; en route to its end, it also serves as access to the Haoe Lead Trail [Fig. 38(6)].

From the parking area, a wooden deck leads to a magnificent view of the surrounding mountains including the Snowbird, Great Smoky, Unicoi, and Cheoah ranges. On a sunny day, Santeetlah Lake glistens in the valley to the right, and the abundant mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) explodes with pink and white blossoms in early June.

This deck is handicapped accessible and offers easy access to a rewarding vista. At an elevation of 3,520 feet, the overlook affords opportunities to watch from above the aerial aerobics of a variety of summer birds such as the broad-winged and red-tailed hawk (Buteo platypterus and B. jamaicensis), cedar waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum), great crested flycatcher (Myiarchus crinitus), American goldfinch (Spinus tristis), indigo bunting (Passerina cyanea), pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus), downy woodpecker, scarlet tanager, and numerous warblers.

Primitive camping sites are abundant throughout the wilderness area, and U.S. forest campgrounds are near the boundary. In addition, the U.S. Forest Service Horse Cove Campground Area [Fig. 38(10)] offers 17 units adjacent to the rushing mountain stream, Little Santeetlah Creek. The campground is located directly across from the entrance to Joyce Kilmer picnic area. Fishing is popular along and in the Little Santeetlah Creek and Slickrock Creek, as well as at nearby Santeetlah Lake (see Santeetlah Lake).