The Natural Georgia Series: The Okefenokee Swamp

|

The Natural Georgia Series: The Okefenokee Swamp |

|

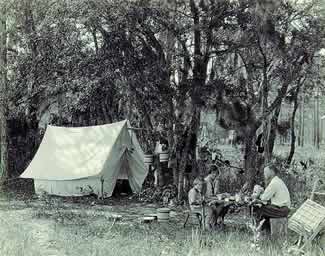

In May of 1912 at the age of 25, Francis Harper was a junior member of a Cornell

University biological team that entered the Okefenokee Swamp. There, the naturalist

found all the biological treasures he expected, and something he came to treasure

maybe just a little bit more. Harper met the swampers of the Okefenokee and

began a career, which spanned more than five decades, capturing the "Cracker"

culture.

His older brother, Roland M. Harper, began calling for the preservation of

the swamp in 1908 and 1909. While his efforts where lost in the rush to log

and make money in the swamp, they inspired a group of Cornell researchers, including

the younger Harper, who explored the swamp for nearly three decades and began

promoting efforts to preserve the Okefenokee as a biological preserve.

In the years to come, local groups, like the Waycross Okefinokee (as Harper

and others insisted on spelling it) Society, rallied around a core group of

scientists and naturalists. While they were not initially successful in persuading

the state or federal government to protect the land, they fought against threats

to the swamp including continuing pressures to log the Okefenokee. In 1929 a

small group of naturalists, most of them from Atlanta, organized the Georgia

Society of Naturalists which remained vigilant and played an important role

in efforts to save the swamp. They lobbied on the state and national level,

published articles in newspapers, and enlisted support from other conservation

groups and individuals, including Daniel Hebard and his son Frederick V. Hebard

who owned most of the Okefenokee.

In the meantime, Francis Harper continued visiting the swamp as often as his

professional obligations allowed. He was paid to go south, visit the swamp,

and collect specimens to take back north. But he also collected folklore - anecdotes,

stories, songs, ballads - and shared those with people around the world. He

kept detailed field notebooks, where he recorded not only what the swampers

did and said, but how they said it, and how they lived. He became an insider,

moving his family to a camp on Chesser Island in the Okefenokee in 1935-1936

while he built a cabin there.

As more people became interested in the Okefenokee, so many different preservation

proposals were presented that it was difficult to build a political consensus

on anything. The Georgia Society of Naturalists remained focused in their efforts

to have the federal government purchase the property as a wildlife preserve.

And in 1931, the society persuaded the U.S. Senate Committee investigating sites

for wildlife refuges to visit the swamp. Although the visit was successful,

the committee was looking for a refuge for waterfowl, and did not think the

Okefenokee was valuable as a migratory bird refuge - others would argue against

the basis of this decision later.

In 1933, the swamp was seriously threatened by a proposal to build an Atlantic-Gulf

Canal across it. The construction effort promised to bring hundreds, maybe thousands,

of jobs to the area - a prospect that was especially attractive in the midst

of the Great Depression. Afraid for the life of the swamp, Francis Harper and

his wife Jean decided to appeal to one of the nation's leading conservationists

and a personal friend, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. After graduating

from Vassar College, Jean Harper had worked as a tutor for the president's children.

Mrs. Harper wrote to the president in November of 1933, asking him to stop

the canal project and to "spend the money in the purchase of the swamp

for a reservation, where beauty and scientific interest may be preserved for

all time." President Roosevelt responded, saying he would hate to see the

Okefenokee destroyed, but did not yet take the matter into his own hands. After

a feasibility study was conducted on the canal project, plans were abandoned.

It wasn't long before a different development scheme threatened the Okefenokee.

By this time it was 1934 and there were plans to build a scenic highway through

the swamp for tourists. The Georgia Society of Naturalists and the Harpers intensified

their preservation efforts, and fortunately state highway funds were seized

by Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge and the project was placed indefinitely

on hold.

Something else important had happened in the preservation effort. Mrs. Harper's

letters to the president were getting through, and in February of 1935 he wrote

to her communicating his personal interest in the Okefenokee. Roosevelt showed

his support by writing letters and memoranda to the Chief of the Biological

Survey and the Secretary of the Interior among others. The Harpers and many

other naturalists who worked to save the swamp claimed victory on March 30,

1937, when the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge was created by executive

order.

For Francis Harper, his preservation efforts had an ironic ending: the formation

of the national wildlife refuge pushed out the swamp community he so loved.

The swampers found it impossible to support themselves when the government told

them they could no longer protect their livestock by killing bears and wildcats.

They moved to small towns around the swamp, and some moved as far away as Savannah,

Macon, and Atlanta. As Harper watched the culture begin to disintegrate, he

struggled to preserve it in writing, in photographs, and on tape.

The Harpers moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he vowed to write

his Okefenokee book but never did. For the rest of his life he longed for the

simpler life he had found in the Okefenokee, and expressed strong feelings against

centralized government, labor unions, and the civil rights movement. He died

on his 86th birthday, never officially preserving the records he collected on

the swampers' culture.

That work was eventually completed and published in a book by Georgia Southern University English Professor, Delma E. Presley. It is called Okefinokee Album, and it is full of not only the words the swampers used, but also those words spelled phonetically to give people an understanding of how the swampers said them. The songs, stories, and anecdotes of the Okefenokee folk are written down now to be enjoyed and preserved. Harper's negatives and photographs, some of the most famous images of the swamp, have been preserved so people can see the swampers' faces. And tape recordings of their words and songs live on so that people can hear the voices of the swampers who were such an important part of the history of the Okefenokee.

Read and add comments about this page

Go back to previous page. Go to Okefenokee Swamp contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]