The Natural Georgia Series: The Okefenokee Swamp

|

The Natural Georgia Series: The Okefenokee Swamp |

|

It's Thursday morning, and Okefenokee Joe is loading up his snakes. A tall,

bearded figure clad in blue jeans and boots and sporting a back-woods accent

and an easy laugh, Joe exhibits a strength and youthfulness that belie his 64

years as he stacks boxes of snakes into the back of his '92 Isuzu Trooper. There

they join a PA system and crates of audio and video cassettes for his upcoming

trip.

By the time night falls, Joe will be long gone from his Southeast Georgia

home, looking for a place to spend the night in South Carolina. Tomorrow morning

he will urge students at a school assembly in Kingstree to respect the environment;

on Saturday he will show his snakes and preach conservation at Cypress Gardens,

a tourist attraction at Monks Corner. This morning, though, he interrupts his

preparations long enough to lead a visitor on a tour of his snakehouse, where

aquarium tanks containing a variety of southeastern snakes line the walls. As

the visitor follows Joe past a line of Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes, one

wakes up, notices the intrusion and starts shaking his rattles.

One of Joe's favorite specimens, a harmless Florida pine snake named Wiggles,

has already taken his place in the back of the Trooper. Common throughout southern

Georgia as well as Florida, the species is readily recognizable by its pointed

nose. This particular snake has been with Joe for a quarter-century and has

helped an entire generation of students in Joe's audiences grow up with a healthier

attitude toward snakes.

"They oughtta pin a medal on him," Joe chuckles.

With several of the snakes removed from the snakehouse for the South Carolina

trip, Joe takes advantage of the opportunity to put fresh paper in the bottom

of one of the tanks. He tears a piece off an end-roll of unused newsprint from

a nearby newspaper, explaining that the chemicals in colored paper would make

his snakes sick. He once told a Wall Street Journal reporter that he bought

her paper all the time. Then he told her the reason: With no color photos in

it, it's ideal for lining his snake tanks.

Joe then leaves the snakehouse and strides down a wooded trail toward Bear

Grass Camp, an encampment where Native American friends sometimes visit him.

As he follows the well-worn path, he talks about his favorite topic.

"It's our earth," he says matter-of-factly. "If we stand on

it, we should be standing behind it."

Yet Joe also understands the economic pressures that environmentalists face.

"It's going to take greenbacks to get the green back," he says.

Walking alongside him as he points out the significance of different trees

and insects and even the stories told by bird droppings, one is quickly lost

in the mystique of Okefenokee Joe. It is as if somehow, during his eight-year

stint as animal curator at the Okefenokee Swamp Park, he became an incarnation

of the Okefenokee Swamp's soul.

Joe invokes that mystique as he travels to school assemblies and nature festivals

throughout the Southeast, using music and his retinue of snakes to help him

proclaim, in eloquently simple and down-to-earth language, his message of environmental

stewardship. Best-known for his specials on public television, he has no advanced

degrees and carries out no formal scientific research. Rather, he is an ecological

apostle, reminding us that we need nature to survive but that she could get

along just fine without us.

"We are an afterthought," he says bluntly.

Through his lectures, his TV shows, his albums, and his videos, Joe tries

to foster an appreciation for wildlife and warns that modern man is tampering

with a natural balance he cannot fully understand, even with all the benefits

of his much-vaunted technology.

"What I teach people did not come from some book or some college course,"

he says. "What I teach people comes from what I see and hear and feel."

Because Joe takes his cause so seriously, he takes his image seriously as

well. Anyone attending one of his programs will never hear him introduce himself

as Dick Flood, the name that he was given at birth and that, in the eyes of

the law, he still holds. To the children who listen with wide eyes to his tales

of the swamp, he is only Okefenokee Joe.

"It's corny," he admits, "but it sells the kids, and those

are the minds I'm trying to reach-to help them grow up with a healthier attitude

about wildlife, snakes in particular and wildlife in general."

Yet the name is no mere showman's affectation. In private conversation, Joe

will tell you, with no hint of theatricality, that something changed inside

him during his years in the Okefenokee. Dick Flood entered the Okefenokee Swamp

in 1973, he will tell you, but it was Okefenokee Joe who came out eight years

later.

Prior to his stint as the Okefenokee Swamp Park's animal curator, Joe achieved

a measure of fame as a songwriter and musician who sang and played the guitar.

Upon getting out of the Army, he and one of his Army buddies teamed up as "The

Country Lads" and immediately secured a spot on The Jimmy Dean Country

Music Show in 1955. Shown on CBS on weekday mornings, the show routinely outdrew

Dave Garroway on the early Today Show on NBC for a year-and-a-half. The show

was so popular that, paradoxically, it was canceled so that Dean could be sent

to New York to be developed as an entertainer. In 1958 Joe moved to Tennessee

and appeared as a guest regularly on The Grand Ole Opry. A year later he assembled

a group, and Dick Flood and the Pathfinders began to make records. In 1962 he

was named the Most Up-and-Coming Male Vocalist in Country Music by Cashbox magazine.

It was also in 1962 that a song he wrote, "Trouble's Back in Town,"

was recorded by the Wilburn Brothers and became the No. 1 country song of the

year. His rendition of "The Three Bells," a No. 1 song on both the

country and pop charts, was so popular (in the 20s on the country charts) that

for the first time in history a separate version of a current hit was listed

on the charts. His version did, in fact, eventually hit No. 1-in India.

The Pathfinders traveled to U.S. military bases across the country and all

over the world, including such places as Italy, Africa, Vietnam, and Labrador.

"I was a poor man's Bob Hope," Joe jokes.

A list of his personal friends during this period reads like a "Who's

Who" of country music stars: Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, George Jones,

Buck Owens, Roy Clark, and Grandpa Jones, to name a few. Dottie West and her

husband once played in his band.

In addition to writing and singing songs, often to the accompaniment of his

own guitar, Joe ran a booking agency and acted as his own agent. He came to

own both a record label and a music publishing company.

Eventually, though, he found juggling so many jobs to be too difficult, especially

with the strain of being both tough as an agent and easy-going as an entertainer.

Also, he was tiring of the business, and circumstances had forced him to change

labels at a crucial point in his career. He drifted from one label to another,

and the gaps between the releases of his songs were too large for him to build

a regular following.

His personal life was falling apart, too. After two marriages and five children,

he found himself in the process of getting divorced from his second wife.

"I was like a wild bear running through the woods, not knowing what direction

to go," he recalls.

In late 1973 he moved to Georgia and became the animal curator at Okefenokee

Swamp Park.

"I always was interested in wildlife," he says. "I'm just very

interested in how wild animals do things and how they survive-their philosophy,

how they behave."

He had first begun to study wildlife as a child, and then, as a traveling

musician, he had made a point of visiting zoos, parks, and exhibits with the

idea of beginning his own exhibit one day. As his own agent, he had been able

to schedule his bookings according to the wildlife. For example, he would perform

in Texas in the spring so he could be with the snake hunters on their yearly

round-ups.

When both his personal and professional burdens threatened to overwhelm him,

the swamp offered him an escape. In retrospect, he says, "I was through

a lot of things. And what was left with me made it to the swamp."

When he met Cindy Yeomans, who would become his third wife, in 1976, he told

her simply, "I'm just bein.'"

For eight years Joe lived on the northern edge of Cowhouse Island in the Okefenokee

Swamp. Before he met Cindy, he was the sole resident of the park.

"When that last automobile left at closing time, I could feel the wilderness

coming back in all around me," he recalls. "I could even hear the

frogs say, 'Are they gone yet?'"

As the park's animal curator, Joe cared for the animals that were being exhibited

and the grounds where they were kept. He also gave lectures, primarily on snakes.

Joe used his time in the swamp to examine nature up close, putting the finishing

touches on his informal study of wildlife. As time passed, he came to cherish

the Okefenokee Swamp and found deeply resonant chords in its haunting beauty,

its profound tranquility, its age-old rhythms, the delicate if occasionally

violent interactions among its flora and fauna, and the primeval balance it

maintains-a balance that seemed more sophisticated to him than the man-made

technology that built nearby Waycross.

The swamp, which had been an escape, became a therapy. Mother Earth "cured"

him, he says, and he experienced a "complete turn-around." Today he

even has trouble remembering details of his life before the swamp-not that he

tries.

"Now is now," he says. "The future is where we're going, not

the past."

While living at the park, Joe cared for seven Virginia white-tailed deer;

five American black bears, including a 400-pounder named Hubert; 13 alligators;

and several raccoons, opossums, skunks, bobcats, and other animals. The animal

he remembers most, though, is a bobcat named Streak.

Streak was a bobcat cub brought to Joe by the Georgia Department of Natural

Resources. DNR personnel sometimes gave him wild animals that they had confiscated

from illegal owners or that had been given to them by people who had acquired

an animal and were unable to care for it.

Joe found Streak to be a smart animal and ended up playing with him and teaching

him to climb trees and catch pinecones in mid-air. At first Streak brought his

kills to Flood, but the bobcat became more and more independent as he grew older.

Joe told the young bobcat, "Go whenever you want. There are 750 square

miles of wilderness out there. It belongs to you, and you belong to it."

One day Streak did leave. First, though, the bobcat jumped onto Joe's shoulder

and hung there for about 10 minutes, almost as if he was hugging Joe before

leaving for the last time.

Joe had given up music completely before moving to the park and for a time

did not even listen to the radio. By the time that Streak came along, though,

he was writing songs in his spare time, and he wrote a song about Streak that

began, "Once I knew a bobcat so quick on his feet / He was faster than

lightning, so I called him Streak."

As Joe developed a following, he began giving lectures away from the park.

He also married a third time, although he is quick to say, "But this is

the first wife I ever had."

In 1981 he and Cindy left the swamp and moved to a house on a country road

between Jesup and Odum in nearby Wayne County. That house serves as a base for

his business ventures, all of which now fall under the umbrella of anhinga Productions,

Inc. When he left the park, Joe's therapy turned into a mission.

The backbone of Joe's work is visiting schools throughout the southeastern

United States and lecturing, with humor and music, about wildlife and respect

for nature. During his lectures, he exhibits some of the 30 snakes that he keeps

for these trips.

At one time numbering 60, the snakes initially stayed on Joe's front porch.

He later built the snakehouse, located down a short driveway from his house.

Jim Fountain, who used to serve as the director of Wayne County's Extension

Service Office and now supervises the entire district, says, "The kids

love him because he's so gentle and personable and all, and he does a good job.

He's a very knowledgeable person in snakes. He's the type of person who can

give you factual knowledge instead of fearful knowledge."

Joe chose to work with snakes for several reasons: because they are in the

middle of the food chain, a better understanding of snakes promotes a better

understanding of wildlife in general; they are easy to carry to schools; and

they are so misunderstood.

The two basic problems people have with snakes, according to Joe, is that

people don't know what a snake will do or what kind a snake is. Southeast Georgia,

for example, contains only about 32 species of snakes, and only a handful of

these are poisonous, he says.

"I prove everywhere I go that just because a snake is poisonous doesn't

mean it wants to bite anyone," he says. "It doesn't even know it can

kill you. I've never known a case where it's the snake's fault that it bites

someone. Even if someone steps on a snake, there's no way it can know that that

person made a mistake."

Most snakebites occur because people go after snakes, he says, adding that

many people do so automatically when they see a snake.

"If a person sees a snake, instead of being overly excited or afraid,

a person should feel relieved," he says. "At least that person knows

where the snake is. If that person knows where the snake is, he can avoid it.

"I've never found a snake that wanted to bite me. But I've also never

found one that wanted to come with me."

Joe is quick to defend snakes and other wild animals, in part because he feels

he has gained so much from his work with them. Of his study of wildlife, he

says, "It's been rewarding-not financially but spiritually. I've learned

a lot about these creatures."

After Georgia's Quality Basic Education Act cut down the number of school

assemblies in the mid-'80s, Joe began a new business to supplement Okefenokee

Joe Enterprises. Power Reduction Systems was affiliated with similar organizations

in other parts of the country and offered to businesses throughout the Southeast

passive techonology, such as phase-liners and fluorescent-lighting controls,

for the conservation of electricity.

"Conservation is the interest," Joe says. "What I do with wildlife

has everything in the world to do with conservation. Now wildlife is America's

renewable resource, and energy conservation is the same as any other type of

conservation. I don't like waste."

As time passed, Joe's natural talent and knack for showmanship led him to

concentrate his interest in conservation into other areas, especially where

music was involved. In 1986 he became interested in the conservation of a man-made

resource, the Statue of Liberty, and wrote a song about "a lady in distress."

Later, as the completion of the statue's renovation neared for the observance

of its centenial anniversary, he reworded the song so that it would be more

positive and not tied to a particular event. The final result is "Ode to

a Lady," which deals with "a lady heaven blessed" and which he

calls "one of the best songs I ever wrote."

Around the same time, in another effort to combine creativity and conservation,

he began writing a children's book, "Rudy Rattlesnake: The Life History

of the Eastern Diamondback Rattler."

Joe's big breakthrough came soon afterward, when Georgia Public Television

made him the subject of a documentary special, "The Joy of Snakes."

Record numbers of viewers tuned in, and GPTV soon followed up with another special,

"Swampwise," named after a song that has become an unofficial anthem

for Okefenokee Joe. The show won a regional Emmy for outstanding documentary.

ven though they have been shown numerous times, reruns of these hour-long

shows still net high numbers for the state's public television network. The

shows are now being aired on public TV stations in major television markets

around the country and are especially popular in Joe's hometown of Philadelphia.

"When I met him, he was such a TV natural," recalls Carol Fisk,

who has produced all of GPTV's specials on Okefenokee Joe. She remembers that

whenever she needed an animal story for one of the specials-for example, a story

about alligators in the springtime-she would just ask him, and he would immediately

think of an incident from his own experience and smoothly recount it for the

camera. "And apart from that, he's just a joy to be around," she says,

adding that his "very charismatic" nature shines through on the TV

screen.

In regard to the shows themselves, she calls "The Joy of Snakes"

and "Swampwise" "evergreens": "Every time we run them,

we're guaranteed a big audience."

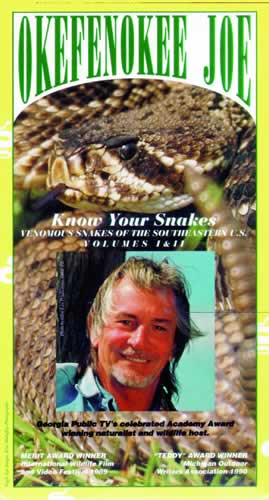

Videos were a logical extension of Joe's work on TV specials, and he developed

a two-video set, "Know Your Snakes," designed to show children and

other viewers the different kinds of snakes that live in Georgia.

The videos have received both the International Wildlife Film and Video Festival's

Merit Award and the Michigan Outdoor Writers Asociation's Teddy Award.

GPTV added a third special, "Okefenokee Joe and Friends," to its

Okefenokee Joe line-up a few years ago. This show, which is only a half-hour

long, features basic, often-forgotten nature and survival skills as demonstrated

by several of Joe's friends, including some of the Native Americans who regularly

visit Bear Grass Camp.

Located next to a pond toward the back of the 120-plus acres where Joe lives,

the camp contains a campfire ring and two chickees. These structures are made

of saplings and palm fronds and harken back to the traditional homes of Native

Americans of the Southeast. Nearby are an outhouse and sapling-and-palm-frond

shower stalls. Around the camp are hawking blocks for practice with tomahawks.

At the entrance to the camp is a hand-painted sign: "Bear Grass Camp-Civilization

Prohibited."

The clearing where the camp is located is smoothly shaped and aligned with

the points of the compass, leading Joe to believe that he built his camp on

a site that had been used for the same purpose centuries ago.

"It's a sacred place," he says. "I'm glad I found it."

Walking around the camp after leaving his snakehouse, Joe softly repeats the

words of a song he once wrote about the site: "There's a place I know where

I can go to hear my favorite songs. / Few would understand that most times I

go alone."

Joe and a group of friends spent a solid week making the cook chickee, using

stripped saplings and 2,700 palm fronds. As big as a large living room, the

chickee boasts not only a stove and other modern appliances but also a place

where food can be cooked over an open fire. The roof and walls are watertight,

but both ends are open to allow smoke from the fire to escape.

The smaller, sleeping chickee, on the other hand, is enclosed on all four

sides. Platforms on both ends provide bed space, while the open area underneath

leaves plenty of space for groups to congregate. According to Joe, the chickee

roofs should last at least 10 years.

Joe has developed a keen interest in traditional Native American beliefs and

skills in recent years, although he is modest about the fact that the Panther

Bend band of the Florida Muscogee Creeks has honored him by "adopting"

him as a member of the band.

From the encampment, Joe turns toward a nearby cabin, which he calls his "high-tech

recording studio." The one-room cabin overlooks the pond and contains a

few plaques and pictures, a makeshift bed on the floor, and some simple recording

equipment on a desk in the corner. Here Joe makes demo tapes.

Yesterday he wrote a song here, drawing on the 18 months he studied black

bears firsthand in the Okefenokee. He starts singing the chorus: "Old black

bear, living in the woods, / Taking life easy like a black bear should. / Wouldn't

change nothin', even if he could - / Old black bear, livin' in the woods."

Surveying the cabin, Joe says, "This is where I do my writin' and thinkin'."

Joe started releasing music albums again in the early '90s, but this time

his songs, like the one about the black bear, deal with nature and fall into

a country-flavored genre he has dubbed "swamp music." His first album,

My Life in the Okefenokee, collected nine songs, including "Swampwise,"

on the Cowhouse Island Record Company label. Now in its second release, that

album was joined in February by a second album, I Saw the Eagle Cry. Both albums

are available on both cassette and CD.

"I think it's the best and most important work I have ever done,"

he says of the new album's 11 songs and eight "earth-spoken messages."

He is still looking for a worldwide distributor for the album, whose cover

depicts a crying eagle against the backdrop of a Native American medicine wheel

with Creek symbols.

In "Keepers of the Earth, Shepherds of the Land," one of the songs

Joe wrote for the new album, fourth-graders and fifth-graders from Oak Vista

Elementary School in Jesup help provide accompaniment on the chorus. It made

sense to have children help with the album, Joe says: "The kids are the

ones who will be responsible for the earth in years to come, after we're long

gone."

"It's a message the kids-and adults as well-need to learn," Oak

Vista principal Wayne Flowers says of the song's theme.

Joe continues to search for new ways to spread his message. In one recent

project, he sold tote bags for school fund-raisers. The bags read "Tote

Me-Save a Tree."

Joe's work, which was profiled by CNN three years ago, has been receiving

even more widespread attention during the past year-and-a-half. In February

of 1996 he was profiled in a front-page story in The Wall Street Journal. In

July "Dateline: NBC" devoted a segment to him. Around the same time

cable superstation TBS prepared a segment on him for the half-hour children's

show "Feed Your Mind!"

The future promises even greater successes for Joe's efforts to spread the

gospel of respecting nature and humanity's place in it. A book he is to co-write

for Longstreet Press in Atlanta is in the planning stages, and mega-publisher

Simon & Schuster has contacted him about the possibility of a book. Meanwhile,

Joe has just signed a contract with the Arizona firm of Raskin and Dalton to

develop a 13-part nature series if the firm can sell the series to one of the

television networks. And Carol Fisk, who is now an executive producer with Georgia

Public Television, says that GPTV is interested in producing another Okefenokee

Joe special next year.

"The important thing is I'm not doing this for Okefenokee Joe,"

he says. "I'm doing this because I think it's necessary for Mother Earth."

According to Joe, the need for greater environmental awareness is becoming

increasingly urgent: "We have got to wake up and realize what we're doing.

You can't keep taking things for granted and expect to survive. I'll put it

this way: If we don't wake up, we'll be glad we found Mars."

Joe plans to be true to his ideals, no matter what future successes come his way. Regardless of how much press he receives, his first priority is to raise awareness about the natural environment-especially among children. "I'm still going to be Okefenokee Joe for the kids," he says. "The world needs an Okefenokee Joe."

Read and add comments about this page

Go back to previous page. Go to Okefenokee Swamp contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]