The Natural Georgia Series: The Fire Forest

Longleaf Pine-Wiregrass Ecosystem

|

The Natural Georgia Series: The Fire ForestLongleaf Pine-Wiregrass Ecosystem |

|

Living

on Longleaf: How Humans Shaped the Piney Woods Ecosystem

Living

on Longleaf: How Humans Shaped the Piney Woods EcosystemFor hundreds of years, the grassland ecosystem helped to define the culture of many southerners who subsisted on these "piney woods." However, much of the cultural importance of this ecosystem dates back far beyond the crack of the cattleman's whip or the clash of Spanish armor which disrupted the calming sounds of the primeval long-leaf forest. For untold centuries, the longleaf pine ecosystem was the lifeblood for indigenous cultures of the southeastern United States. Sadly, a complete understanding of this culture is lost in oral history or scattered across plowed farm fields throughout the southern states. As such, evidence that early man utilized the environment around him is easy to document yet it is difficult to determine the degree of his impact. However, one thing is for certain: These native people should not be viewed as noble yet uninformed savages who lived benignly with their environment, taking only what was absolutely needed for survival. It can be assumed with some certainty that given their number, distribution, and activities, indigenous cultures of the Southeast had a significant effect on the composition of the longleaf ecosystem.

Over the millennia, the face of the southern landscape has changed with the ebb and flow of the earth's climate. Some 14,000 years ago, the immense Laurentide ice sheet covered much of the North American continent, creating a climate that favored a mixture of boreal forest, oak scrub, and open savanna in much of the present longleaf ecosystem range. The first people arrived in the southeastern United States during this time as small, nomadic bands of hunter/gatherers who specialized in hunting herds of Ice Age elephants, and other megafauna such as long-horned bison, camels, and giant sloth. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, along with the retreat of the ice-sheets 10,000 years ago, the climate began changing into what it is today.

For the nomadic bands of hunter/gatherers, warming weather marked the beginning of a new way of life and triggered cultural adaptations. With the disappearance of large prey from overhunting and climate change, early man conformed his hunting practices for the pursuit of smaller, more solitary game (like deer) that began to radiate out across the Southeast. With increased success in hunting and gathering, populations began to increase. The itinerant lifestyle of these hunter/gatherers began to change. Larger groups were becoming restricted to smaller territories. Bands of Indians began to focus their activities along specific water drainages such as the Chattahoochee, Tombigbee, Apalachicola, and Thronateeskee (Flint) Rivers.

The discovery of agriculture led to more reliable food stores, which in turn led to further increases in population. With the exception of the fertile red clay soils (like those found in the Red Hills of Georgia) it is doubtful that the deep sandy soils found in much of the Coastal Plain proved suitable for Indian agriculture. Instead, the planting of maize, squash, and beans was generally relegated to the rich bottomlands near rivers and streams. By the time Spanish explorers arrived in the sixteenth century, many areas of the Southeast contained densely populated, sociologically complex Indian chiefdoms.

The forest remained a significant source of food, medicine, tools, housing materials, and clothing for most indigenous cultures in the Southeast. Lightning-ignited fires played a role in creating these desired provisions; however, because these fires were stochastic in character (and thus unreliable), Indians purposely burned areas to perpetuate many of the desired plants and animals in the forest around them. Over time, frequent fires began to mold a forest comprised of fire-tolerant longleaf pine and other plant species.

Tribal legend of the Alibamo Creek Indians states that Fire belonged to Bear in ancient times. However, one day Bear neglected Fire and it nearly extinguished. People heard the cries of the ailing Fire and fed it with sticks and brush. From that point on Fire belonged to human beings. As many land practitioners understand today, the Indians realized fire was a powerful tool that could be used to manage habitats suitable for preferred game animals. Purposely burning the forests not only attracted deer to areas of lush, new growth but also made it possible for deer numbers to expand by increasing their food supply. The use of fire kept the longleaf pine forest open, giving hunters better shooting access. Fire was also used to corral fleetly animals in open areas.

Certain cultures practiced wildlife management for species other than deer. The Muscogulges (Creek Confederacy) highly valued black bear as a game animal. Thus, each Creek talwa (town) maintained a nokose-em-ekana or "beloved bear ground" of preferred habitat composed of canebreaks and hardwood forests. Indigenous people's survival was based on an understanding of how to manage a mosaic of different habitat types.

The

Discovery of a New World

The

Discovery of a New WorldIn 1539, Hernando de Soto led 640 Spanish soldiers, tradesmen, and priests into Florida. Traveling along well-established Indian trails, de Soto and his men fought their way from Indian town to Indian town in search of precious metals. The open and parklike longleaf forests once favored by the Indians provided little refuge against a well-armed and mounted Spanish cavalry. To provide food for his expedition, de Soto brought along cattle and Spanish herding pigs. Many pigs escaped, and their descendants, later known locally as the "piney woods rooters," became a serious threat to longleaf pine seedling regeneration for countless generations to come.

Soon after de Soto's expedition, other Europeans began to conquer the vast "unclaimed boondocks" of the New World in the name of discovery, and native populations plummeted. It was not death from the sword, however, that decimated these indigenous cultures; an invisible enemy introduced by these early explorers took a far greater toll on Indian populations than weapons ever did. European and African diseases to which the natives had no immunity plagued village after village, destroying much of the South's indigenous population in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It is estimated that upwards of 90 percent of the native population succumbed to diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza. In the late 1700s, naturalist William Bartram noted "endless wastes, presenting rocky, gravelly and sandy barren plains, producing scarcely any vegetable substances, except a few shrubby, crooked pine trees, growing out of heaps of white rocks, which represented ruins of villages planted over the plains." As the region's population of humans dropped, that of the while-tailed deer and other game animals rose. Some have suggested that during this time, bison moved into the longleaf pine ecosystem.

As the interest of Europeans in their newly acquired American colonies continued to grow, so did their interactions with the remaining Indian populations. Gift exchange was an important gesture to assuage tensions between the two cultures. However, over time, the desire of both sides for increased goods and profit began to dominate this trade. Deerskins traded to English tanners purchased "modern" tools, weapons, and clothing for the Indians-things the longleaf forest could not supply. Of the southeastern Indian tribes, none was more eager and adept at trade than those of the Creek Confederacy. Armed with modern weapons, those Creeks involved in the buckskin trade became more efficient and successful in attaining deer.

For the Creeks, the use of fire and fire drives increased as hunting pressure continued to mount. One such drive was noted in 1708 by a visitor to the longleaf pine flatwoods:

Three or 4 hours after the ring is fired, of 4 or 5 miles circumferance, the hunters post themselves within as nigh the flame and smoak as they can endure. The fire on each side burns in toward the center and thither the dear gather from all parts to avoid it, but striving to shun a death which they might often escape, by a violent spring, they fall into a certain one from the bullets of the hunters who drawing nigher together, as the circle grows less, find an easy pray of the impounded dear, tho seldom kill all for some who find a place where the flame is less violent, jump out. This sport is more certain the longer the grownd has been unburned. If it has not for 2 or 3 years there are so many dry leaves, grass and trash, that few creatures within escape.

Another

visitor to the pine woods in 1769 echoed similar observations of the Indians'

use of fire: "The hunting parties of the Creek Indians, who are dispersed through

the whole province, continually set the grass on fire, for the conveniency of

hunting."

Another

visitor to the pine woods in 1769 echoed similar observations of the Indians'

use of fire: "The hunting parties of the Creek Indians, who are dispersed through

the whole province, continually set the grass on fire, for the conveniency of

hunting."

A conservative estimate of buckskin production in the late eighteenth century suggests about 1.5 million pounds of leather per year were supplied to the market (about 1 million deer). As the trade intensified, deer populations became depleted and eventually the markets shifted to other products like cotton textiles. Many tribes were forced to turn to livestock and plow agriculture of "Old World" crops as a substitute. Over time, the cultural unity and heritage of the indigenous cultures began to erode, replaced by European ideals and practices. Today only place names bestowed by once prodigious indigenous cultures stand as evidence to their occupation of the longleaf pine woods.

At the close of the Revolutionary War, Georgia was the weakest of the 13 states. Although its people were not the fewest in number, its territory was the most extensive and occupied by the most numerous and warlike Indian tribes. Nevertheless, the massive longleaf pines and luxuriant carpet of grasses left a favorable opinion in the minds of the officers and soldiers who had passed over the land several years earlier. It was generally Carolinians of Scotch-Irish descent who braved the terrors and hardships of the longleaf pine barrens where rice or cotton plantations failed to penetrate. A German traveler to the longleaf pine backcountry in 1783 found cattle, swine, and these piney woods people "here denominated crackers." These backcountry yeomen were notorious for being "brutish in behavior," excellent animal husbandmen and hunters, but indifferent farmers, living in the pinelands "beyond the reach of all civilized law."

These frontier people of the longleaf woodlands were genuine herdsmen. In the longleaf uplands, abundant bunchgrass furnished a cheap source of forage for the scrub cattle of these cracker cowboys. When traveling through the wiregrass country of Georgia, William Bartram noted "numerous herds of cattle" that were "peaceably browsing on the tender, sweet grass, or strolling through the cool, fragrant groves of the surrounding heights." By 1860, three quarters of a century later, cattle and other southern livestock were worth half a billion dollars-more than twice the value of that year's cotton crop.

The herding practices of these pioneer hog drovers and cattle drivers of the piney woods were distinctively Celtic in origin. Included in this ideology was a vehement opposition to enclosures. Typically, fences only enclosed a few acres of "cowpen" land on which subsistence crops were grown. Cows and hogs were simply turned out in the customary Celtic tradition of open-range herding. As a rule of thumb, it generally took about 10 acres of native grasses to keep one cow well fed throughout the year. Crackers' notorious "resentment of outsiders" stemmed in part from a desire to maintain sufficient range for their stock. Range was often so unrestricted that it was not unusual for an animal to wander away beyond returning or finding. The search for this stock, wrote historian J.C. McRae, could often be hindered by "the rattle of the rattlesnake and the cry of a panther" which could send the searcher "home in a hurry from the woods."

The

pastoral economy of the cracker culture also encouraged the habitual use of

fire; another tradition of Celtic origin meshed with the Indian practice. Wildlife

biologist Herbert Stoddard recalled these nineteenth-century piney wood's cattlemen

"had used fire liberally for generations . . .setting fires at intervals when

conditions were right for light burning, from early fall to late spring. They

knew from the way cattle gravitated to the fresh burns that the tender grass

would make them grow and fatten." Besides its use for maintaining palatable

grasses for cows, woods-burning was thought to be beneficial by killing snakes,

ticks, chiggers, and fever germs. To keep wooden structures from being consumed

by these frequent range fires, dirt yards were meticulously swept of debris,

creating firebreaks (a tradition that can still be viewed in many rural areas

of Georgia). Woods-burning was so common it was estimated that 105 percent of

Florida burned in many years, a result of semiannual range fires. It would be

this promiscuous use of fire that would in the early twentieth century pit cattlemen

against a forest industry that saw its use as detrimental to the value of the

forest.

The

pastoral economy of the cracker culture also encouraged the habitual use of

fire; another tradition of Celtic origin meshed with the Indian practice. Wildlife

biologist Herbert Stoddard recalled these nineteenth-century piney wood's cattlemen

"had used fire liberally for generations . . .setting fires at intervals when

conditions were right for light burning, from early fall to late spring. They

knew from the way cattle gravitated to the fresh burns that the tender grass

would make them grow and fatten." Besides its use for maintaining palatable

grasses for cows, woods-burning was thought to be beneficial by killing snakes,

ticks, chiggers, and fever germs. To keep wooden structures from being consumed

by these frequent range fires, dirt yards were meticulously swept of debris,

creating firebreaks (a tradition that can still be viewed in many rural areas

of Georgia). Woods-burning was so common it was estimated that 105 percent of

Florida burned in many years, a result of semiannual range fires. It would be

this promiscuous use of fire that would in the early twentieth century pit cattlemen

against a forest industry that saw its use as detrimental to the value of the

forest.

The procurement of food, shelter, and medicine on the longleaf pine frontier was filled with uncertainty and peril. Self-sufficiency was essential, and the survival of this cracker culture was inextricably linked to the fruits of the longleaf ecosystem. The axles of every pioneer wagon that moved through these woods were lubricated with the tar extracted from the lightwood of longleaf pine. Pioneers' first permanent residences were built from the heart pine timbers of ancient longleaf pine trees. Hands bruised and blistered as immense trees fell from the axe and boards were laboriously cut in pit saws. These essential tasks of life in the piney woods could easily result in serious or even fatal injury. Access to trained medical practitioners was often a day's ride or more from town. Crackers learned to gather the herbs, animal simples, or minerals needed to concoct various homemade nostrums from the woods around their homes. Other products of the longleaf pine tree were also considered a panacea for many ailments. Pine bark, turpentine, rosin, tar, and needles were administered internally and externally for a variety of derangements (most notably for respiratory complaints). Pine tar was also used as a wound dressing for livestock.

Food was secured from the vast woodlands since the piney woods were largely considered unsuited for large-scale agriculture. Numerous berries, plants, and animals flourished in the pine uplands and hardwood bottomlands. The gopher tortoise was highly valued for its succulent meat, earning it such nicknames as "cracker chicken" or "Georgia bacon."

The gopher tortoise also played a significant role in local economics when paper currency was scarce. As noted by a Florida resident, "almost every grocery store had a line of pens" that held "gophers of different sizes from 10 cents to 35 cents." People coming in from the country would bring in a load of gopher tortoises to trade for groceries. "I have seen a man come in with a 25-cent gopher and buy 10 cents worth of something and then put his gopher in the 25-cent pen and take out a 15-cent gopher for change."

By the end of the nineteenth century, the longleaf pine frontier was merely the fading memory of a few white-haired wranglers, their hands rendered feeble by decades of arduous work, faces creased and spotted by the Georgia sun. The expanding appetite of postbellum recovery opened the door for King Cotton, timber, and naval stores industries to move into the region. Gently rolling hills and ancient groves of longleaf that once echoed the social voices of livestock were now filled with the shouted commands of the tenant farmer to his mule, the songs of turpentine crews, and the assaulting screams of logging machinery. Free-range was quickly becoming an idea of the days past. Without adequate range to raise enough livestock for profit, many cowmen were forced to hang up their spurs and turn to cotton production. Yet, somewhere in those hardened eyes of that cracker cowboy, the fire of the open range piney woods still burned.

From

King Cotton to Bobwhite

From

King Cotton to BobwhiteUp until the Civil War, the interior of Georgia remained largely an undeveloped and rather primitive area. During the rush for cotton lands, most settlers with dreams of farming bypassed the deep sands south of Georgia's Fall Line. For this reason, many of the towns in the longleaf pine sandhills lacked a robust economy based on commercial agriculture. Railroad investors often passed up these impoverished communities, prolonging their isolation. During this time, pockets of plantation-style cotton farming existed mainly on the more fertile soils that could support cotton production.

In the depression of post-Civil War recovery, cotton served as common currency throughout much of the South. To make ends meet, many landowners were eager to abandon the poverty of subsistence farming on marginal soils for cotton production. Many emancipated slaves and deprived whites were forced into peasantry as tenant farmers (sharecropping) in order to put food on their tables. Few sharecroppers possessed the disposable income to purchase their own cultivating implements, draft animals, or seeds and thus were tied to the landowner for subsistence.

By the late nineteenth century, the demand for cotton exports began to fall. To compensate for falling prices and rising debt, more acres of longleaf forests were cleared and planted in cotton-enslaving many farmers into further debt. As the cotton market continued to dwindle, many farmers were forced to give up the title to their lands and become tenants themselves. Despite large increases in populations and number of farms, southern agriculture began to regress during this time.

In the years following the Civil War many wealthy travelers from the North also found themselves in the piney woods of areas such as Thomasville, Georgia. The medical advice of that day claimed that pine trees exuded some type of vapor that assisted in the treatment of various respiratory ailments like tuberculosis. Others came to escape the hordes of mosquitoes that plagued many coastal cities or to find a warmer climate in the winter season.

Travelers to the Thomasville area found that the frequent fires of the longleaf pine woods nourished healthy populations of bobwhite quail, considered one of the most challenging game birds to hunt. In the depressed economy of the Reconstruction period, countless acres of virgin longleaf pine forests were for sale. Many wealthy Northern sportsmen purchased this longleaf forestland and established luxurious quail hunting plantations amongst the longleaf of the Red Hills. Having acquired these virgin forests prior to the era of mass-logging that was soon to follow, several quail hunting plantations around Thomasville still retain the finest examples of old-growth longleaf forests in all of the Southeast. Land for quail hunting plantations around the Albany, Georgia area would not be purchased until several decades later during the Great Depression when cutover timberland literally sold at a few dollars per acre.

The aristocratic landowners of these extravagant hunting plantations of the Red Hills were the minority. In the years that followed the Civil War, the majority of the populace living amongst the piney woods was impoverished tenant farmers and cowmen, often living from hand to mouth. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the longleaf pine woods were beginning to attract the capital of significant commercial enterprises such as timber and naval stores.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the longleaf pine region was responsible for producing 70 percent of the world's supply of naval stores-the collective name for products such as tar, pitch, spirits of turpentine, and rosin obtained from pine trees. A century earlier, the dominance of North Carolina in the production of turpentine earned it the title of the Tarheel State (for the black gummy tar that would accumulate on the bare feet of workers). It was the highly resinous wood (often called fatwood) of the longleaf pine tree that made it so desirable and sparked the naval stores industry throughout the Southeast. The term naval stores was originally applied to pitch and tar needed for waterproofing the wooden sailing vessels of the Royal British Navy in the seventeenth century. In fact, British sailors earned the nickname "tars" from their practice of dipping their nappy hair braids in pine tar. As the industry evolved, the distillation of fatwood kindling shifted to the processing of pine gum extracted from the living longleaf pine tree. Around 1850, the production of gum turpentine peaked in North Carolina and began to spread south into Georgia as northerly forests were exhausted. However, it wasn't until the years following the Civil War that the production of turpentine in Georgia began to rapidly increase.

Gum from the pine tree was distilled into rosin and spirits of turpentine in what has been described by many as an "oversized liquor still." The collection and processing of pine gum was a year-round ordeal and often required a large labor force. Work was physically demanding and often began when the sun broke through the tree line and ended as darkness was cast across the sky. Dripping with sweat from a relentless heat and harassed to the verge of insanity by constant swarms of gnats, laborers would work their way from tree to tree chipping shallow gutters (called streaks) into the fresh wood of the tree face. This cut face would direct the gum down into a box notched into the bottom of the tree by a broad axe. However, these boxes were often very destructive to the pine trees-essentially girdling the tree at its base. In the early years of the twentieth century, technology improvements allowed gum to be collected in clay or metal cups hung from the tree by a nail.

A squad of workers traveled from tree to tree dipping gum from the cups and depositing it into barrels. When a worker finished his task on a tree, he would sing out a particular name he had chosen for himself (usually this was a town). A talleyman would record this song with a dot. The number of dots determined a worker's pay. Barrels of gum were hauled to a nearby distillery and refined. In the winter season when gum production slowed, brush and other debris were raked from around trees to prevent the tree face from catching fire. Despite the flammability of raw gum running down a tree face, woods were often deliberately (yet skillfully) set on fire by turpentine men to keep the ground clear of thick shrubs and vines so a turpentine crew could move about easily and as a proactive means to lessen the threat of wildfires set by cracker cowmen.

To house laborers, crude shantytowns (called quarters) were often constructed by employers. An onsite commissary provided groceries, work clothes, and other supplies for laborers. Once a month, scrip would be issued to the workers that could usually only be redeemed at that operation's commissary. For this reason, few workers would ever find themselves free from debt. A laborer could move to another operation only after his debt was cleared. Sometimes, this led to the "pirating" of one operation's workers by another operation's recruiter. However, pirating was a dangerous business, with mistakes sometimes paid for with a recruiter's life. For those workers who received legal tender, payday often meant drunkenness, shootings, and knife and fist fights as farmers, wranglers, and turpentine workers converged on the small towns dotted throughout the longleaf woods of Georgia.

Along with the naval stores industry of the longleaf pine flatwoods, a unique culture evolved. "I got my education through a pine tree," recalls Dr. T.I. Brooks of Colquit, Georgia, his mind dancing back to a period of his youth when his senses were consumed by the perfume of pine rosin and the cheerful banter of workers from his daddy's naval stores operation. C.W. Wimster, a veteran of the turpentine woods, recollected with similar fondness, "Yeah man, I was bawn in a turpentine camp, spent near about 40 years in the business, and woulda been in it yet if the bottom hadn't a dropped out of it. I've soaked up so much turpentine in my life that if you run me through a still right now, I reckon you'd git about 10 gallon outa me." Mayo Livingston Jr. of Cyrene, Georgia still recalls a time when the songs of turpentine crews could be heard floating through his airy pine forest: "Waycross, Mobile, Seaboard." As the songs of the turpentine crews faded so too did a unique industry and culture. In the end, the naval stores industry of the southern pine forests would lose out to cheaper markets overseas and to better substitutes.

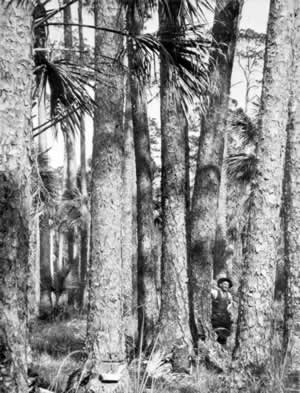

The exploitation of the longleaf pineries for timber began in the years following the Civil War with the harvesting of many pine stands bordering rivers and streams. Massive longleaf pines were felled with hand axes or crosscut saws, skidded to the water by oxen teams, assembled into rafts, and floated to sawmills. Many of these dense logs heavy with resin sank during their transport to mills. These sunken logs (often called deadheads) can still be found today littering streambeds throughout the Southeast. Operationally it wasn't practical to skid logs in excess of 4 miles. For this reason, sizeable areas of backcountry longleaf forests remained out of the reach of many timbermen.

The exhaustion of the pine forests in New England by the end of the nineteenth century saw northern investors purchasing large areas of southern lands covered with vast acreage of longleaf pine. With this investment came advances in technology to reduce costs and step up production. Tram lines for railroad logging penetrated the virgin backcountry. Inefficient oxen teams were replaced with powerful, steam-powered skidders that could handle five or six logs at one time. Logging train hoggers (engineers) commanded flatcars loaded heavy with longleaf pine logs down unsteady rail lines to colossal sawmills capable of cutting over 80,000 board feet per day.

In order to meet the manpower requirements needed in logging operations, lumber companies often enticed members of the local populace to fill unskilled labor positions by offering higher wages than could be obtained through sharecropping. To house this labor in close proximity to sawmills, towns such Babcock, Georgia were hastily constructed by these logging companies in the late nineteenth century. The highly valued heart pine lumber from the longleaf pine assured that many logging towns throughout Georgia would prosper for years. Often, concessions such as a commissary, hotel, and segregated churches and schools were built within these towns. Because lumber operations were fraught with hazards, some towns would provide company doctors.

In 1900, Dr. Carl Schenck, head of the Forestry Division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture preached that the "virgin forest in which the old and decrepit trees predominate is unproductive . consequently the virgin forests should fall and must fall." And fall they did. Little regard was given to forest conservation or sustainability at the time. The idea was simply to "cut out and get out" and by 1909, the peak of longleaf pine lumber production was reached. The extraordinary demand for every merchantable stick of timber, the pitiless system of taxing every board foot of standing trees, and the insatiable appetite of the piney woods rooter assured that many areas were stripped clean of trees. Barren, cutover land stretched wearily away from rusting rail lines as far as the eye could see. By 1923, author R.D. Forbes noted, "The plain truth of the matter is that in county after county, in state after state of the south, the piney woods are not passing, but have passed. Their villages are Nameless Towns, their monuments huge piles of sawdust, their unwritten epitaph: The mill cut out!" Today, the only evidence of once-booming logging towns like Babcock is a few brick foundations scattered amongst fields of weeds.

During the years of the Great Depression, Civil Conservation Corp enrollees began to plant large areas of cutover land with pine seedlings. The forestry community at the time saw longleaf pine as a slow-growing tree, difficult to regenerate. So, in place of longleaf, loblolly or slash pines were carefully planted in dense, tidy rows, amid the skeletons of the ancient longleaf pine forests. This new crop of seedlings was less tolerant of fire than the longleaf pine trees. In order to protect this new investment of trees, a crusade spearheaded by the Southern Forestry Educational Project was initiated to preach that fire was a destructive agent in the landscape and needed to be snuffed out. Their mantra was simply this: "So long as fire is kept out of the woods, the community of trees and plants and animals have a chance to take care of themselves." Later the torch of fire suppression would be passed off to Smokey Bear.

Those who assisted in the perpetuation of the longleaf ecosystem for countless generations through their culture of woods-burning were now labeled firebugs, arsonists, and community ne'er-do-wells. The long-standing tradition of setting the woods on fire was now distorted by the popular press of the day as an action to merely "provide entertainment for a people who dwell in an environment of low stimulation and who crave excitement." A new era of fire suppression loomed on a horizon once hazy from the smoke of the burning longleaf pine forest.

Over time, the forest industry would come to understand the importance of fire in maintaining the longleaf pine ecosystem. However, the seeds of change had been planted. Several decades of fire suppression had sealed the fate for many longleaf pine forests that had survived the axe or the hungry hog. Longleaf pine seedlings, plants, and animals that depended on the open pine forest maintained by fire languished as they smothered underneath an impenetrable thicket of briars, vines, and shrubs.

From the end of the mass-logging era to present, the longleaf pine ecosystem has continued to steadily decline with every passing year-a few hundred acres clear-cut here, a few thousand acres plowed under for agriculture there, etc. The landscape of manicured tree farms or immense farm fields seen today along the interstates or dusty dirt roads of rural Georgia bears little resemblance to the vast stretches of open and airy longleaf pine forests that existed as recently as 150 years ago. As the longleaf forests disappeared, so too have the cultures that evolved with them. Today, the only evidence of these once diverse cultures is often relegated to museum curios or dusty books hidden on library shelves. Unless the trend of the destruction of the longleaf pine forests is reversed, few of the next generation of Georgians will be able to gaze upon and feel a physical or even spiritual connection to the once magnificent piney woods of the South.

Read and add comments about this page

Go back to previous page. Go to Fire Forest contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]