The Natural Georgia Series: Barrier Islands

|

The Natural Georgia Series: Barrier Islands |

|

Georgia's string of subtropical barrier islands boast a rich and lengthy cultural history. Relics of ancient coastal Indians reveal that thousands of years passed between the first generation of children born to aboriginal residents and the winds that blew the large cloth sails propelling European ships. During the sixteenth century, Spanish and French explorers first set foot upon the sandy shores of the islands. Both countries laid claim to the lush coastal lands, but the Spaniards proved strongest. Although many Georgia history books spend little more than a few sentences on Spanish heritage in the pre-Oglethorpe period, missions of considerable size and permanence thrived well into the seventeenth century and reflect extensive Spanish activity.

With the eighteenth century came the English and the beginning of the most influential era in the state's history as studied by Georgia schoolchildren. Fertile acres were cultivated extensively and English colonists prospered from the export of indigo, rice, hemp, and flax among other agricultural products. Finally the stars and stripes replaced the union jack, but with the outbreak of the Civil War, even the stars and bars of the Confederacy managed a short reign. After the plantation era and its peak of Sea Island cotton production, tycoons flocked to the barrier islands during the latter part of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Today, picturesque ruins still stand-remnants of missions, forts, slave dwellings, and mansions. Colossal live oaks, their moss-draped branches ever extended, welcome conservationists to certain areas along the coastal terrain and vacationers to others.

The Creeks, one of the so-called Five Civilized Nations of Indians, inhabited Georgia's barrier islands long before Europeans set sail for the New World. A nomadic people, they moved from one village to another with the changing seasons, following migratory wild fowl, fishing the inland streams, and hunting alligators in the coastal rivers and buffalo and deer on the mainland. They cultivated corn, melons, squash, beans, tobacco, and fruit, and possessed insatiable appetites for oysters.

It has been said that these native inhabitants were not mound builders like so many other Indian tribes, but on Ossabaw Island-located 20 miles below Savannah-shell mounds exist. Excavations have revealed mostly kitchen middens or massive piles of oyster shells: evidence that Ossabaw was once a favorite Creek hunting, fishing, and feasting ground. One of the largest Creek villages, with headquarters for the chieftain of the tribe, was situated south of Ossabaw on St. Catherines Island; a high promontory on this island's eastern side overlooks both beach and sea and no doubt provided a natural vantage point for the Creeks.

On Sapelo Island, a 12-foot shell wall encloses a space at least 60 yards in diameter-nearly the size of a football field. This ancient shell ring, or arena, dates back some 5,800 years and is one of the oldest remnants of Indian activity along the Georgia coast. As legend has it, the arena was formed by a Creek chieftain who tossed aside shells, day after day, as he sat on the ground cross-legged and feasted on oysters delivered to him by runners who fetched them directly from the ocean. Sea Island, St. Simons, and Jekyll share similar prehistoric backgrounds of Creek inhabitation. Only Cumberland Island was occupied by the Timucuans, a Florida tribe whose customs and language differed from those of the upper island Creeks.

Among the first traders said to have traveled to the coast were tribes from north Georgia who followed the Old Indian Path from the Appalachians to the Atlantic. With weapons, tools, and arrowheads of stone and flint they arrived, wishing to trade for dried fish, fowl, fruits, and herbs. Of particular interest were the dried leaves of the cassina, which grows in abundance along the coast and was used to brew a potent ceremonial tea. Arrowheads, made from stone that is not native to the Georgia coast, comprise portions of contemporary public and private collections.

Beyond domestic trade, the coastal Indians established foreign trade relations during the sixteenth century. According to Burnette Vanstory, author of Georgia's Land of the Golden Isles, they supplied French ships with "cargoes of sassafras, animal skins, wax, rosin, and wild turkeys. It has been said that people in France were enjoying turkey from the Southern coast long before the first Thanksgiving feast of the pilgrims."

During the 1560s, early explorers like Frenchman Jean Ribaut with his band

of Huguenots and Pedro Menéndez and his Spanish fleet staked their claims

to these islands. But certain evidence suggests an even earlier European settlement

along Georgia's barrier islands. Dr. Paul Hoffman, professor of history at Louisiana

State University, suspects that 60 years before the demise of Sir Walter Raleigh's

"lost colony" at Roanoke, the Spanish tried and failed to gain a foothold

in the New World. It was along Georgia's barrier islands, not at Roanoke or

Jamestown or Plymouth Rock, according to Hoffman, that America's colonial history

truly began.

The year was 1526. Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, a royal judge residing in Santo Domingo, led a voyage of 500 men and women, including African slaves and Dominican friars, to establish a Spanish colony called San Miguel de Gualdape. Attempts to settle, however, were short lived. Indians soon attacked and disease quickly spread; Ayllon and more than 200 other settlers died. Less than three months after its founding, the Spanish colony was abandoned.

The site of San Miguel de Gualdape has yet to be uncovered while attempts to pinpoint its location have been plagued by controversy. Using sketchy and often conflicting records, many historians have concluded that the colony was near Georgetown or Port Royal, South Carolina, or even near the mouth of the Savannah River. But within the last 15 years, reprinted accounts of early Spanish voyages in the New World (originally published in the 1530s) "strongly suggest that Gualdape was on Sapelo Sound," says Hoffman. Despite squabbles over location, there appears to be no doubt about the year of settlement, 1526: 39 years before the founding of St. Augustine, 81 years before Jamestown, 95 years before the arrival of the Mayflower, and 207 years before Oglethorpe sailed up the Savannah River to colonize Georgia. Confirmation of Ayllon's settlement-the first European establishment in North America-would surely require a revision of history.

Dr. David Thomas Hurst, an anthropologist employed by the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, is working to foster greater interest in Georgia's Spanish epoch. The author of St. Catherines: An Island in Time, Thomas's research has shown that the Spanish mission system in Georgia (and Florida) "was founded earlier.involved more people and lasted longer" than its better-known counterparts such as the Alamo and others in the American West. "Understanding of the past has always been heavily conditioned by attitudes of the present," explains Thomas. "The early missions of Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California still remain highly visible. It is no coincidence that hundreds of volumes have been written on America's western missions."

Once the French under Ribaut were driven off of the barrier islands by Menéndez and his Spanish fleet, Santa Catalina de Guale was established on St. Catherines Island in 1566. It is considered part of the first settlement north of Mexico deemed for regular Spanish mission work. When Thomas began searching for Santa Catalina on St. Catherines, he knew that for nearly 100 years the mission was the "northernmost Spanish outpost on the Eastern Seaboard, and this historical fact implied considerable size and permanence." As anticipated, he and a team of archaeologists uncovered evidence of a fortified church, buildings to house soldiers and priests with granaries, storehouses, and dwellings suitable for hundreds of Guale (another name for the Creeks pronounced "wallie") Indians.

Mission priest learned the Indians' language and converted thousands to Christianity between 1566 and 1680. In addition to teaching and converting natives, the priests spent time tending their gardens-a profusion of tropical vegetables, fruits, and flowers. A legacy to the Georgia coast from its early white inhabitants, groves of oranges, lemons, pomegranates, olives, and figs would continue to bear fruit long after Spanish occupation.

Although the majority of natives were friendly toward missionaries, some resented the outsiders. Buckling under the harassment of hostile Creeks, several missions were destroyed and Jesuit friars eventually driven out. In the 1570s, mission work was zealously reorganized by Franciscans and pursued for decades, but troubles for priests persisted. With English colonists in close proximity to the barrier islands, English traders provoked friction between Indians and Spaniards and goaded pirates sailing the coastal waters to come ashore and plunder missions. But Santa Catalina de Guale persisted, and in the early 1600s, Juan de Las Cabeza de Altamirano, the Roman Catholic bishop stationed in Havana, Cuba, came to the Georgia coast to praise the work of missionaries and baptize Guale leaders.

In 1732, King George II issued a charter for James Oglethorpe and 19 associates to colonize Georgia. The territory to be settled lay between the Savannah and Altamaha rivers; England and Spain had agreed to leave the region below the Altamaha as a sort of no man's land. So it was left to Oglethorpe, British general and philanthropist, to secure the path towards development of this 13th colony. Oglethorpe developed a three-fold plan. It included establishing a defense against the Spaniards in Florida; creating a haven for Protestant dissenters, insolvent debtors, and the criminal classes of England; as well as developing a new source of revenue for the Crown.

In 1733, General Oglethorpe first touched American soil on Tybee Island, approximately 18 miles from the site where he would found Savannah. Upon his arrival, Oglethorpe and the Creek Indian Chief Tomochichi became fast friends. The general's dealings with the natives were, from the start, remarkably successful. Tomochichi soon persuaded the Creeks to peaceably turn over possession of the chartered territory, and the town of Savannah was founded later that year. Settling upriver was as strategic a move as Oglethorpe's plans for mass fortification along the coast. Oglethorpe selected the island of St. Simons for fortification against Spanish invasion. He ordered construction of a fort on St. Simons's west side where a bend in the river formed a natural vantage point. Built in 1736, this British fort, one of the largest in colonial America, provided protection for other colonies as well as the town within its walls. Fort, town, and river were called Frederica in honor of Frederick, Prince of Wales. The town rapidly grew around the fort as Oglethorpe encouraged craftsmen, artisans, shopkeepers, and their families to settle there. But after the British victory at the Battle of Bloody Marsh, the regiment disbanded, and many settlers left for other parts of the colony. In 1758 a fire destroyed the town and it was never rebuilt.

Numerous other forts, both colonial and American, were constructed over the next 150 or so years. Savannah's strategic wartime importance contributed to the construction of two fortifications near the city. In 1808, a brick structure surrounded by tidal moat, Fort Jackson was built on Salter's Island near Tybee. The second, Fort Pulaski, was built in 1829.

In keeping with the land agreement between Oglethorpe and Tomochichi, the Creeks retained Ossabaw Island along with neighboring St. Catherines and Sapelo for their hunting grounds, but with British influence the names of the other islands became Anglicized. Previously San Pedro, Cumberland Island was given its English name soon after the colony of Georgia was settled. In 1734 when Tomochichi and his family visited England, the chief's nephew, Toonahowie, kindled a friendship with William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the 13-year-old son of the king. As the Indian family's four-month visit came to an end, Prince William presented Toonahowie with a gold watch. Deeply touched by the gesture and the relationship the two had shared, the Indian prince requested the name of San Pedro be changed in honor of William Augustus.

Perhaps the most intriguing instances of nomenclatural evolution were those experienced by Jekyll Island. Jekyll was a favorite haunt of the Creeks who called it Aspo. In the 1560s, the French Huguenots named the island Ile de la Somme. Over 150 years later, General Oglethorpe changed its name once again-this time to honor Sir Joseph Jekyll, a gentleman who had helped him finance the colony of Georgia, but Jekyll locals have long since contested such aristocratic ties to the island's most recent name. As word-of-mouth history goes, a Frenchman named Jacques operated a trading station for pirates and buccaneers here in the 1600s. The name Jacques' Island deteriorated into Jake's Isle, then Jakyl. Spelled Jekyl for many years, an extra "l" was eventually added making Jekyll the accepted spelling.

By the 1740s the Georgia colony had proved its worth as a buffer against Spanish forces but had yet to establish itself as a source of income for the mother country. Oglethorpe believed the cultivation of fertile acres along the coast would surely reap profit. During these early stages of agricultural development, planters were encouraged to grow indigo for the production of dyes, mulberry trees to make silk, and vineyards for wine. Of the three, indigo thrived; in a time before synthetic dyes, it rapidly became one of the colony's chief exports. According to a record dating back to 1756, other agricultural products from the coast included rice, pitch, tar, hemp, flax, vegetable wax, and beeswax. Lumbering and cattle-raising also earned profits for the colony.

Prosperous planters made their way to the lush barrier islands and shared in the success for more than a decade. But soon the thunderous boom of Revolutionary War cannons forced island inhabitants to flee. Fields were later plowed and replanted, but with the War of 1812 the coast was again subjected to enemy raids; Fort Jackson, off of Tybee, was among the coastal forts garrisoned.

Between the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, a process called "live oaking" became a booming business. Before the advent of metal-hulled ships, live oak was one of the world's most sought after lumber types for the construction of battleships. A dense, heavy wood with many curves and a twisted grain, live oak is resistant to rotting and weathering. Such qualities made live oak ships superior war vessels. Reports of British cannonballs bouncing off the hull of the U.S.S. Constitution, a live oak ship employed during the War of 1812, gave it the name Old Ironsides. As such reports spread worldwide, a demand for live oak in both domestic and foreign markets skyrocketed. Unfortunately, 400 to 700 live oaks were required to build the frame of just one ship, and Georgia's barrier island forests were ravaged. Procuring live oak became increasingly difficult. This problem coupled with the inception of "ironclad" steam-powered ships diminished the live oak trade by the mid-1800s.

The barrier islands now flourished in what author Burnette Vanstory described as "the high noon of the plantation era." White land, black labor.

Ossabaw Island was among the first of Georgia's coastal empires. The cultivation and processing of indigo prompted the transfer of hundreds of slaves to the island. Field hands were used to cut the plants at daybreak before the hot sun could dry the leaves. Vat workers then immersed the leaves to draw out the dye while others stirred the extract with paddles for aeration. Skilled men handled the dye's actual preparation, boiling its sediment with water then draining and pressing it into molds. Once dried in the sun, the molds of indigo were loaded upon barges headed for Savannah to then be shipped to foreign markets. Ossabaw bustled with its plantation house and slaves' quarters, its field hands and dye workers, and its docks and loading crews.

Late in the eighteenth century, colonists determined that the subtropical barrier islands were decidedly ripe for the cultivation of a certain species of cotton. Colonists who sought refuge in the West Indies during the American Revolution found it there. Seed plants brought to the Georgia coast were said to be developed into the most superior brand of cotton ever grown. The long-fibered cotton could be easily separated from the seed.

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, coastal plantations made agricultural history. From Sapelo and St. Simons on down to Cumberland, island fields were white with cotton. Even Ossabaw turned over its profitable indigo fields to the growth of Sea Island cotton upon learning it demanded up to twice the fee for ordinary cotton in markets throughout the world. Crops of Sea Island cotton brought many plantation owners up to $100,000 per year.

Planters built sprawling estates, entertained lavishly, and coveted the finer things. Life on the island empires, however, was best categorized with contradiction-elegant yet primitive. Indeed there were all the luxuries and delicacies of the Old World as enjoyed by the duBignons-a noble family who came to American to escape the French Revolution in 1789-on their 11,000-acre Jekyll domain planted in cotton. The duBignons lived like the French landowners from whom they descended. The family residence was decorated with furnishings, paintings, and ornaments from France, brought by their sailing vessel the Commodore on her annual voyage to the motherland for supplies. But such seclusion from the outside world could prove dangerously inconvenient. Sudden illness had to be treated with home remedies. Communication was dependent upon boat travel and if turbulent weather made waters impassable, island inhabitants were forced to rely on their ingenuity.

Despite the prosperity reaped from the cultivation of cotton, certain agricultural experts expressed concern. Thomas Spalding, an authority on Sea Island cotton, foresaw the potential danger of exhausting energies on one crop to the exclusion of others. A resident of Sapelo Island, he successfully introduced sugar cane to the barrier islands as an alternative cash crop; with so much cotton being produced at once, a surplus seemed imminent. One of the earliest advocates of diversified farming, Spalding regularly made speeches and published articles urging farmers to rotate their crops. His insight was a modern concept, one touting the importance of conserving nutrients in the soil.

Just as Spalding predicted, cotton production peaked, and the demand and price declined. Near the middle of the nineteenth century, England experienced a recession, and the coastal island docks backed up with bales of cotton. Plantation soils also became exhausted. Before long, rampant infestation of boll weevils destroyed the crops.

Headman upon the Spalding plantation was a famous slave called Bulallah, believed to have been born in the French Sudan. Bulallah enjoyed the complete confidence and respect of his master and of all the men who came under his supervision. Father of a score of children, Bulallah has hundreds of descendants living today in the coastal region. Many are said to have inherited his copper-toned skin and features as well as his height. His descendants are proud of their ancestry and pass down tales of the old man. Bulallah was wise in the ways of nature. His children and his children's children knew the secrets of the moon, the tides, the waters, and the forests. When one family member fell sick, the elders related to Bulallah knew which herbs and roots to gather and how to concoct the proper medicinal brew. Joel Chandler Harris's Story of Aaron mentions a book written in Arabic by Ben Ali (another name by which Bulallah is called). This volume is prized among rare books at the Georgia State University Library located in Atlanta.

The majority of slaves relegated to work upon the coastal empires did not enjoy the confidence and respect of their masters. An Englishwoman by the name of Frances (Fanny) Kemble recorded the day-to-day operations and conditions of plantation life on St. Simons. After marrying a wealthy Philadelphian, Pierce Bulter, whose family fortune was partly derived from a vast cotton and rice plantation, Kemble lived on the island for several months. In her book, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839, Kimble expressed disdain for "the manifest injustice of unpaid and enforced labor; the brutal inhumanity of allowing a man to strip and lash a woman, the mother of 10 children; to exact from her, toil, which was to maintain in luxury idle young men, the owners of the plantation." Her account is one of backbreaking slave labor endured in miserably high temperatures and unbearable humidity, and of the harsh cruelties inflicted regularly upon slaves by their white masters. Kemble also details the plantation's landscape of swamps and woods, canals and rivers, stately mansions and decrepit hovels.

Today a square brick chimney is all that remains of a steam-powered rice mill on the Butler plantation. A roadside marker near the site mentions Kemble's Journal "which is said to have influenced England against the Confederacy." Although it hardly affected international diplomacy, the book (which first appeared in 1863 in England, then in the states) did cause controversy in the North and South. In the South, Kemble was denounced as a meddling foreigner who stood in judgment on matters with which she had merely a passing acquaintance. She was also accused of distortion and exaggeration. But in the North, her accounts furthered the cause of many abolitionists. Skeptics of Kemble's Journal remain critical today. They cite several willful misrepresentations as evidence of unreliability, and point to a book published after the war by Kemble's daughter, Frances Leigh, that contradicted her mother's accounts.

During the Civil War in the 1860s, most of the barrier islands were evacuated at some stage before the Confederacy surrendered. Those residing on St. Catherines and Ossabaw departed immediately. For a time in 1861, Confederate troops were stationed upon Sapelo Island.

Numerous forts on the barrier islands earned mention in the history books thanks to their roles in the Civil War. On January 3, 1861, in one of the first military actions of the war, Georgia troops seized Fort Pulaski (located on Cockspur Island near Tybee) from Federal hands. Only 15 months later, Union troops occupying Tybee recaptured the fort. When construction of Fort Pulaski began in 1829, one of its engineers-soon after his graduation from West Point-was Second Lieutenant Robert E. Lee.

Fort Jackson, previously a colonial fort also located on a barrier island, served as the Confederate headquarters of the river batteries during the Civil War. An interior brick fort guarding Savannah's river approach, naval vessels never overcame it.

Troops of the Confederacy were also stationed at the south end of St. Simons with instructions to guard the entrance of the Brunswick harbor. But a few weeks shy of New Year's Day 1862, Union gunboats blockaded the coast and the residents of St. Simons were ordered off the island. Eventually Confederate troops were evacuated from St. Simons Island-long ago a military stronghold where General Oglethorpe strategically constructed Fort Frederica to stave enemy invaders away from the colonies. Bitter yet weary soldiers followed their final orders and blew up the St. Simons lighthouse to keep the light from aiding the victorious blockaders. With St. Simons and Brunswick in the hands of Union forces, the island was used as a concentration area for freed slaves from the mainland.

Some of the first black troops to see action in the Civil War had been stationed on St. Simons Island. The Massachusetts 54th, the U.S.C.T. regiment commanded by 25-year-old Col. Robert Gold Shaw, fought against Sherman's armies who looted and burned the town of Darien, located on a channel of the Altamaha River near Savannah, in 1863. The battle was made famous by the movie Glory.

In the years following the Civil War, a number of barrier islands were taken over by squatters and plunderers, which infested the South during Reconstruction. Federal forces had previously pillaged coastal island plantations until they became inoperable and owners fled. Some of the former plantation slaves who remained farmed for subsistence, but before long owners returned. Loosely organized sharecropping and land-bartering arrangements were made between the two. Attempts, however, to reestablish antebellum cotton plantations failed under these working conditions. Plantations simply could not operate without enforced labor; the work required was that treacherous, as the former slaves knew all too well. The plantation era came to a close.

But before the war's end, the present state of Sapelo Island's cultural history began to take shape. The remaining Spaldings on Sapelo, two daughters-in-law of the late Thomas, undertook the task of sailing slaves to the mainland. Upon arrival, they marched them over 160 miles to the interior of the state. Those too young or too old to walk were left behind to fend for themselves.

Once freed, many former slaves from Sapelo struggled their way back to the

coast, then back to the island (many to reunite with family). An order by Sherman

granted abandoned land on the coastal islands and a section of the Georgia mainland

in 40-acre allotments to the freed people. Those returning to Sapelo set to

work at once, cultivating soil and building a schoolhouse and church. A community

began to emerge. But this autonomy did not last long as power shifted from Sherman's

General Saxton to a General Tillson.

By 1871 three Sapelo men scraped together a down payment on 1,000 acres at Raccoon Bluff, which they divided into 33-acre plots and sold to former Spalding slaves. Although it was not a prosperous community, as people subsisted on what they could grow and fish, Raccoon Bluff became Sapelo's dominant community by the end of the nineteenth century.

In 1911 the last of the Spaldings sold the greater part of the island to Howard Coffin of the Hudson Motor Company, and in 1934 Coffin sold it to tobacco heir R.J. Reynolds. By 1950, Reynolds had set aside the northern half of Sapelo Island for a game preserve, but Raccoon Bluff stood in his way. Because Reynolds held economic power over the black community, the Sapelo people moved, although reluctantly, to parcels in Hog Hammock.

After Reynolds' death in 1963, the northern half of the island was sold to the state. A few years later, Georgia bought the rest, except for Hog Hammock. Today, approximately 70 people-many descendants of the legendary slave, Bulallah-reside in the Hog Hammock community. Geechee, their West Africa-influenced dialect (known as Gullah along the South Carolina coast), is still spoken by some. Many Hog Hammock residents have committed themselves to the preservation of their community, keeping traditions such as southern-style cooking and storytelling alive.

One resource, still abundant on the coastal mainland and on some of the islands, was lumber. From 1870 to 1900, the short-lived lumber period occurred in response to an increasing international demand for southern lumber. St. Simons and Doboy Island, a tiny marsh island south of Sapelo, became the sites of lumber mills because of their river locations. Cypress, pine, cedar, and oak were cut from flourishing mainland forests; the logs were then floated down the Altamaha and Satilla rivers to island mills where they were sawed into lumber for export. St. Simons and Doboy sounds were stocked with great schooners from all parts of the world waiting to purchase the lumber. Simultaneously, residents of Sapelo Island made a thriving business raising cattle and selling beef to the captains and crews of the schooners. This bustling period rapidly ended as the trees suitable for lumber were depleted.

During this period following the Civil War, barrier islands such as St. Catherines and Ossabaw seemed to evolve full circle. With fields overgrown enough to provide cover for birds and game, they appeared as they had centuries ago as the roaming and hunting grounds of the Creek Indians.

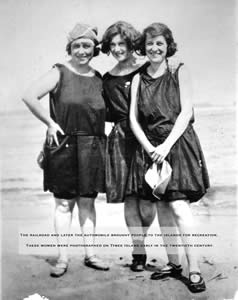

Of the barrier islands in the latter part of the nineteenth century, Vanstory wrote lyrically, "Devastated and deserted and weary with war the islands dozed in the sun; time healed their wounds, and nature covered their scars with the lush green of vine and fern and the profligate beauty of the tropical flower." The Georgia coast attracted vacationers and naturalists alike who were bedazzled by nature. At the dawn of the twentieth century, the barrier islands entered a new period of prosperity and five of the islands became the property of America's wealthiest tycoons.

Between 1886 and 1942, American millionaires faithfully wintered on Jekyll Island. Astors, Rockefellers, Morgans, Vanderbilts, Macys, Pulitzers, and Goodyears took leave of Fifth Avenue penthouses and retreated to the serenity of the Georgia coast. For 56 years Jekyll remained their exclusive playground; visitors were referred to as strangers and allowed to stay on the island for two weeks only. The "simple life" that these leading American financiers chose to lead on Jekyll often included wild-boar hunting parties followed by 10-course meals prepared by a chef imported from New York City's Delmonico's Restaurant. Residing in multiroomed "cottages," the rich and famous played golf and tennis and socialized.

St. Catherines Island, purchased in 1876 by John J. Rauers of Savannah, became home to one of the finest country homes and private game reserves in the nation. The home of a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Button Gwinnett, remains on St. Catherines.

Once

the Torrey family settled into their home on Ossabaw after acquiring the island

in 1924, the hospitality of plantation days was restored. An oversized leather-bound

guest book, first signed by the Henry Ford family, boasted many a well-known

name with the passage of very little time.

Once

the Torrey family settled into their home on Ossabaw after acquiring the island

in 1924, the hospitality of plantation days was restored. An oversized leather-bound

guest book, first signed by the Henry Ford family, boasted many a well-known

name with the passage of very little time.

During World War II, the famous millionaires of Jekyll departed for the last time. In 1947, the State of Georgia purchased the island for the bargain price of $675,000. Since then the number of private houses built in residential areas has dramatically increased. Closer to the beach are tourist developments such as motels, restaurants, a convention center, an aquarium, and shopping centers. A public fishing pier and an amphitheater for summer play were also built with vacationers in mind.

Continuous development of subdivisions and shopping centers bring more permanent residents and traffic to the narrow, tree-lined roads on St. Simons each year. On the more exclusive Sea Island, the famed Cloister resort is still rated among the finer hotels in the nation and continues to attract international clientele. These islands also attracted the attention of famous writers, such as Eugene O'Neill, who wrote Ah Wilderness here, and Eugenia Price, the best-selling author of a trilogy of books set on St. Simons.

On other barrier islands, the state and federal government have taken control

of the conservation of coastal terrain. In 1969 the tiny island of Wassaw was

sold to The Nature Conservancy provided that no bridge ever be built connecting

it to the mainland. Deeded to the federal government that same year, it is now

preserved as a national wildlife refuge. Virgin forests cover ancient dunes

and help to protect and increase island wildlife, and today Wassaw is a popular

hunting destination. The 5,600 acres of woodlands, lakes, and marsh on Blackbeard

Island also remain as an unspoiled natural haven, and Blackbeard is one of the

seven coastal refuges administered by the U.S. Department of Interior Fish and

Wildlife Service.

Ossabaw is also bridgeless and destined to stay that way. In 1961 the island's private owner, Eleanor Torrey West, created the Ossabaw Island Project Foundation for "men and women of creative thought and purpose." The foundation soon gained a reputation as a high-quality, if slightly eccentric organization. Lengthy waiting lists for admission to the select group were comprised of artists, craftsmen, scientists, philosophers, photographers, poets, and writers. Each paid a reasonable weekly fee to work in the idyllic setting. The author Ralph Ellison and composer Aaron Copland were among the better-known residents. The Georgia Department of Natural Resources now operates the island, and only those who obtain special permission from the agency can visit Ossabaw.

Cumberland Island has remained largely wild. In the early 1970s, the federal government established the Cumberland Island National Seashore and opened part of this national treasure to the public. Visitation to St. Catherines, on the contrary, has become extremely limited. In 1974, the island entered what must have been the most unusual period in its varied history when it became one of the New York Zoological Society's Rare Animal Survival Centers. Acres that were once white fields of Sea Island cotton, then pastures for herds of black angus cattle, became grazing areas for exotic animals from such far-away places as Uganda, the Sudan, Kenya, the Sahara, and South America. In addition to the work of the animal survival center, a number of archaeological explorations have been undertaken on St. Catherines, such as those headed by Dr. David Thomas as part of his Santa Catalina de Guale excavations. Guest visitation today is quite difficult to obtain.

Two islands, Tybee and Skidaway, are accessible by the causeway off the coast of Savannah. Tybee opens its 5-mile beach to the public, but Skidaway is a private residential area with golf courses and recreation area developments. The University of Georgia Marine Research Extension Service, located on Skidaway, offers some research trips.

Read and add comments about this page

Go back to previous page. Go to Barrier Islands contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]