Jutting into the sea between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico for more than 400 miles, the Florida Peninsula looks like a land caught in a tug of war between the United States and the Caribbean—a sort of half-sister to both, not fully a part of either. Nowhere is this dual nature more evident than in the Everglades and the Florida Keys, where plants and animals, and even cultures from both worlds, live side-by-side in a unique and remarkable land.

The two distinct yet connected coastal regions covered in this book are the

Florida Keys and the Everglades. The Florida Keys encompass a loose string

of 822 islands scattered from Biscayne Bay just south of Miami to the Dry Tortugas,

about 200 miles to the southwest. Thirty-two of the islands are inhabited and

a few, like Key Largo, Islamorada, Marathon, and Key West, are heavily developed

for tourism.

The Everglades is a low, flat plain shaped by the action of water and weather—a unique geologic feature that contains habitats found nowhere else in the world. A watery marsh of some 4,000 square miles, the Everglades covers much of the tip of the Florida Peninsula from Lake Okeechobee south to Florida Bay and the Ten Thousand Islands. It includes the famous river of grass, the Big Cypress Swamp, the Ten Thousand Islands, the vast Everglades mangrove backcountry, and Everglades National Park. For more specific information on geology and history of the Keys and the Everglades, see Florida Keys, page 27, and the Florida Everglades, page 153.

Unlike many coastlines where one road winds along the shoreline leading from one scenic or historical site to the next, the roads leading to the coast along the tip of Florida travel straight to the sea. One of these roads, the incredibly scenic Overseas Highway (US 1) skips for 100 miles across the Florida Keys to Key West following the route of the original Flagler railroad. Everything that happens in the Keys starts somewhere along this road.

A few miles to the west there's a road of discovery that crosses through Everglades National Park on the way to Flamingo, a small National Park Service community on the very tip of the Florida Peninsula. The park road literally crosses sawgrass prairies and travels past pineland forests, dwarf cypress forests, and tropical hammocks. It ends on the shore of Florida Bay, a body of water made famous by television anglers and a struggle to protect this important estuary.

On the southwestern coast there's State Road 29, which passes through the Big Cypress Swamp on its way into the middle of the Ten Thousand Islands. It ends on the rustic and historic Chokoloskee Island and on the edge of the Everglades National Park's mangrove backcountry. It's a road that has brought outlaws, drifters, and millionaires to the edge of the wilderness.

Connecting the southwestern and southeastern coasts, and cutting across the tip of the peninsula, is the famous Tamiami Trail (US 41), a scenic highway that is its own attraction. Crossing through the heart of the Everglades, it cuts across the Shark River Slough and right through the middle of the Big Cypress Swamp. Along the road you'll discover numerous opportunities to explore these extraordinary lands.

The Everglades and the Florida Keys basically have two seasons. A warm, humid season runs from May to November, during which about three-quarters of the 57 to 60 inches of annual rainfall falls. (The Keys average only about 40 inches of rain per year). A much more pleasant, cool, dry season lasts from December to April.

Summer temperatures can reach the mid-90s for many days in a row. Winter temperatures

average around 70 degrees Fahrenheit, but can rise into the mid-80s during

any month, or drop into the low 50s when occasional cold fronts push far enough

south. Frost in South Florida is extremely rare.

Located at the northernmost extreme of the tropical belt and the southernmost point in the temperate belt, the Florida Peninsula's climate evolves from temperate in the northern panhandle to tropical in the south. Although technically even Key West is 1 degree above the Tropic of Cancer, the warmth provided by the Gulf Stream creates a true tropical climate in extreme South Florida and the Keys.

Literally a river within the sea, the 45-mile-wide Gulf Stream carries warm tropical waters from west to east between Cuba and Key West, and then up along the southeastern coast of Florida. In the lower Keys, the deep blue waters of the Gulf Stream can be seen just outside of the barrier reef.

Trade winds blowing predominately from the southeast steadily carry the warmth of the Gulf Stream and Caribbean waters across South Florida, creating a true tropical weather pattern. As a result, Key West is the hottest city in America with a year-round average temperature of 77.7 degrees Fahrenheit. Miami falls second in that category at 75.6 degrees Fahrenheit.

Overall, Florida has the highest average temperatures nationwide. Yet the moderating trade winds also protect South Florida from the triple-digit summer temperatures that occur in more northern climes.

South Florida's unique climate, geology, and balance between temperate and tropic climates have created a vast interconnected mosaic of unique natural features and unusual habitats populated by a great diversity of plants and animals.

Tropical hardwood hammocks flourish on coastal ridges, islands, and on ground that is slightly elevated above the level of neighboring marshes and other wetland habitats. They are found both in the Florida Keys and the southern portions of the Everglades. Some of the finest examples can be seen on the northern end of Key Largo and in Everglades National Park.

Dozens of native West Indian plant species can often be found in a single hammock. Most began as seeds brought here by winds, tropical storms, tides, or migratory birds. More than 200 varieties of West Indian species of trees, vines, ferns, mosses, and lichens have been identified in the region.

A typical hammock is made up of four major structural parts: the canopy or overstory, the midstory, the understory, and the ground cover. The canopy contains the tops of the largest trees such as gumbo-limbo (Bursera simaruba), Jamaica dogwood (Piscidia piscipula), and poisonwood (Metopium toxiferum). The mix of smaller trees in the midstory often includes black ironwood (Krugiodendron ferreum), pigeon plum (Coccoloba diversifolia), and Spanish stopper (Eugenia foetida). Young canopy tree species are also found in the midstory mix. Tropical shrubs in the understory and ground cover include wild coffee (Psychotria nervosa) and cockspur (Crataegus crus-galli).

The hammocks also support a variety of birds, small mammals, and butterflies, including the endangered Schaus' swallowtail (Heraclides aristodemus).

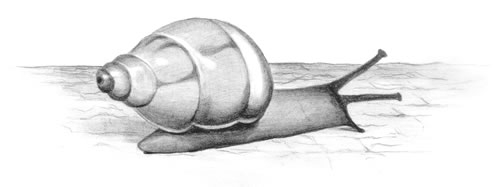

One interesting hammock-dweller, the Florida tree snail (Liguus fasciatus) is a very colorful, hard-shelled mollusk that feeds on the bark of trees growing in tropical hardwood hammocks. During summer, tree snails can be seen crawling slowly along, scraping off and ingesting fungi, lichen, and algae. In the winter dry season, they seal their shell to a tree with a gluey mucus and wait for the next wet season.

A state species of special concern, the Florida tree snail, like many other Florida creatures, has been undone by its beauty. The snails' 1.5- to 3-inch whorled shells, which range in color from white to buff to yellow and are often brilliantly striped in pink, yellow, green, and white, make them a natural collector's item.

Due to long isolation the snails in some individual hammocks have actually developed distinct color variations. To date, there are 58 separately named color forms. Tragically, some collectors took advantage of this evolutionary situation by gathering as many snails as possible from a specific hammock, then burning the hammock to insure the uniqueness of the snails they intended to sell.

Pine rockland forests grow out of thin layers of porus caprock (limestone) and oolite substrate. In the United States they are found only in South Florida with examples in Everglades National Park and the middle region of the Florida Keys.

The pinelands have an upper canopy, an understory or subcanopy, and a thin layer of ground cover plants. Although there is little underbrush, frogs, snakes, insects, orchids, and ferns live in soil accumulated in deep crevasses and holes in the porus, rocky surface.

Slash pine (Pinus elliottii) is this woodland community's predominant tree. Maturing at 120 to 130 feet, it has a crown rounded to a flattened top, long yellow-green needles, and cones up to 6 inches in diameter. Along with a variety of birds and small mammals, animals found here include white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginia) on the mainland and endangered Key deer (Odocoileus virginianus clavium) on Big Pine Key and No Name Key.

Periodic fires are one of nature's ways of safeguarding the health of the pinelands. A thick bark almost impervious to fire protects adult pines. In addition, needles are found only near the crown of the trees and lower limbs drop off as the tree grows taller. At full maturity, the lowest limbs may be 30 or 40 feet above the ground, well away from any fast-moving brush fire.

Fires forestall an accumulation of dead wood and dried organic matter, which could result in catastrophic fires that might reach into the upper canopy and destroy the mature trees. They also keep in check the hardwood understory that would shade out pine seedlings and eventually replace the pines.

A number of venomous and nonvenomous snakes make their home in the pinelands and along nearby wet areas. The Eastern coral snake (Micurus fulvius fulvius) grows up to about 2 feet long and is distinguished by alternating black, yellow, and red bands. Normally not aggressive, the coral snake's bite paralyzes the nervous and respiratory systems and can be fatal if antivenom isn't injected within a short time.

The Eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus), a member of the Pit Viper family, is one of the more feared reptiles. It coils and shakes its tail rattles as a warning before striking, although it can also strike without coiling. Normally not aggressive, it will on occasion stand its ground.

The dusky pigmy rattlesnake (Sisturus milarius barbouri) is also a member of the pit viper family. It matures at about 2 feet in length and is gray with three rows of black spots. The pigmy rattlesnake's warning rattle can sound like a cricket or a grasshopper. It is found both in marshes and pine woodlands.

The Florida cottonmouth moccasin (Agkistrodon piscivorus conanti) can sometimes be spotted swimming in fresh water with its head patrolling above the surface like a submarine periscope. Dark brown, with wide yellowish brown bands, it usually avoids human contact but its bite can be deadly.

The nonvenomous yellow rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta quadrivittata) is also very common in the Everglades and can often be spotted slithering up a tree. As its name suggests, the snake feeds on rodents, which it bites and squeezes to death. When disturbed the snake releases a strong smelling musk, which acts like catnip to wild cats.

The Eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon corais couperi), also known as Florida's blue indigo snake, is the largest snake in America. Reaching lengths of 8 feet or more, the nonvenomous species suffers from overcollection and habitat destruction. It's protected as a threatened species in Florida.

Mangrove forests are one of South Florida's most important natural features. The mangrove tree has adapted so well to living in a saltwater environment that it is the prevalent plant found in gently sloping shoreline areas regularly washed by low tidal wave intensity. Trapping detritus with their roots, the trees also provide food and habitat for a variety of crabs, fish, mollusks, and insects.

Brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis), great white herons

(Ardea herodias), magnificent frigatebirds, white-crowned pigeons (Columba

leucocephala), double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus),

and Anhingas (Anhinga Anhinga) roost and nest in mangrove trees. Water

snakes and raccoons forage among the mangrove roots, and American crocodiles (Crocodylus

acutus) rely on the forest as a sanctuary from man.

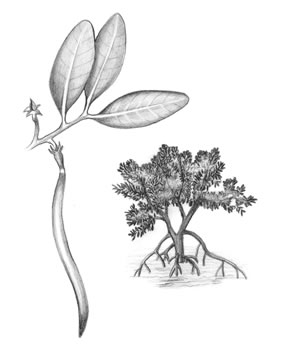

Three mangrove species are prevalent in the Everglades and Keys. The red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) is the most dominant member and the species found nearest to the water. It has elliptical dark green leaves and long green seed pods that drop into the water and can float for miles before taking root. The tallest member of the mangrove family, usually growing to an average of 20 feet, it anchors itself against the tide with hundreds of reddish-brown prop roots that arch from the trunk and take hold of the muck below the water. The black mangrove (Avicennia germinans) is the second tallest species. Its oblong leaves have a salt-encrusted underside, and tasting the leaf is one way to tell the black from other mangroves. Its twisted aerial roots, called pneumatophores, that jut up like cigars or skeletal fingers all around the base of the tree, are the plant's respiratory organs. Indians and early white settlers burned black mangrove wood as a mosquito repellent.

The shrublike white mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa) is the smallest of the three species. It favors higher ground and grows away from the shorelines, often forming hammocks along with tropical species like West Indian mahogany (Swietenia mahagoni) and gumbo-limbo trees. It can be identified by wide, flat leaves with rounded ends and seeds that look like small peas. Its fruit is red when mature.

Buttonwood (Conocarpus erectus) is a member of the white mangrove family and is found most often in swamps and hammocks at least 2 feet above sea level where tidal flooding is unlikely. It has 4-inch elliptical leaves, gray to dark brown bark, and small greenish flowers in egg-shaped clusters.

Stretching along the Atlantic side of the Florida Keys is the only living coral reef system in North America and the third largest barrier reef in the world. Each year millions of snorkelers and divers come to discover this alien yet startlingly beautiful world.

Composed of coral structures that grow one upon the other, coral reefs are one of the most complex of all ecosystems. Florida's coral reefs, which extend from Biscayne Bay to the Dry Tortugas, are estimated to have taken from 5,000 to 7,000 years to develop.

Every coral structure is actually a colony made up of thousands of microscopic, soft-bodied animals, called polyps. Each tiny polyp extracts building material—calcium—from the sea and uses it to make a protective tube-type skeleton. Hundreds of these skeletons make a coral. Untold numbers of corals growing side by side and on top of each other form a reef.

The reefs then become host to a diverse community that includes sponges, shrimp, crabs, turtles, lobsters, and fish. Any unoccupied hole, crack, or ledge quickly becomes a home, and every bare spot a likely anchor site.

Many of the Keys' vast array of marine invertebrates can be found on or near the reefs, including sponges, sea anemones, jellyfish, and of course several species of living coral. Beautiful to look at, some invertebrates are dangerous to humans who come into contact with them. Fire sponge (Tedania ignis) can be recognized by its brilliant red or orange coloration and wide, irregular lobes. Anchored to coral, rocks, and mangrove roots, it causes serious rashes and blisters. Crenelated fire coral (Milepora alcicornis), which is actually a hydrozoan disguised as a creamy-yellow, tree branch-looking coral, is covered with small, white, hairlike tentacles that cause a serious rash.

Made obvious by their 9- to 10-inch-long, gas-filled, balloon-shaped bodies, with blue and pink highlights, Portuguese man-of-wars (Physlia physalia) are often seen floating on the ocean surface in large schools or washed up on the beaches. Their stinging 50- to 60-foot tentacles can cause severe burns and blisters, which should be treated immediately. Meat tenderizer or warm water applied to the welts will help to break down the poison proteins until medical help can be obtained.

Tropical reef fish like sergeant majors (Abudefduf saxatilis), butterflyfish, and parrotfish rely on multicolored displays of bars and stripes to help them hide from predators against the colorful reef. Reef fish popular as sport-fishing targets include a wide array of snappers and groupers, which take up residence in available holes and beneath ledges in the reef.

Barracudas (Sphyraena barracuda), which average from 2 feet to 3 feet long but can grow much larger, cruise through the water column above the reef and are regularly caught by anglers. The barracuda's massive lower jaw, with pointed, protruding teeth, makes it a terrifying sight and potential danger to swimmers and divers. However, it rarely intentionally attacks humans.

Beyond the reefs, the waters of the Gulf Stream beckon to charter boats stationed in the Keys that carry clients into the warm waters to troll for wahoo, dolphin, king mackerel, bonita, yellowfin tuna, and blackfin tuna. Perhaps the greatest prize is a chance to tangle with a trophy sailfish or marlin. Atlantic sailfish (Istiophorus platypterus), which are members of the Billfish family, are dark blue and silver and they mature at between 6 and 8 feet in length. They are distinguished by two spectacular dorsal fins that can be folded into a groove on the back for increased speed when pursuing prey on or near the surface. Underwater, groups of sailfish unfold their sails to herd schools of smaller fish.

Blue marlin (Makaira nigricans), also a member of the Billfish family, are one of the Keys' most prized trophy fish. Today, very few fish are killed to make trophy mounts; instead a replica is made of the catch, which is released alive. Marlin are found in deep open seas, where their speed helps them capture tuna, squid, and other prey. They mature at 6 to 12 feet, and fishermen rarely capture one of these silvery-blue fighters without an exhausting battle.

Cypress domes and broad cypress strands dominate inland coastal areas where the water is slightly deeper than in the grasslands. Domes are dense clusters of cypress trees growing in water-filled depressions in the landscape. The depressions are widening solution holes in the porous limestone rock caused by rainfall that becomes slightly acidic after percolating through the surface layer of organic material.

Although they require occasional droughts to germinate, cypress trees can survive in year-round standing water their entire life. The dome shape results from trees in the deeper soil at the center of a depression growing taller than those on the outside. Stunted cypress trees, called dwarf cypresses, are a result of poor soil and dry land. While only a few feet tall, they can be as old as their stately brothers.

Huge cypress strands are found in the Big Cypress Swamp. The word strand refers to linear swamp forests that develop along large sloughs in the Big Cypress Swamp. These densely vegetated forests may contain thousands of acres of cypress trees and stretch for up to 20 miles. The sloughs are created by water flowing over and beneath the landscape, slowly dissolving the limestone base.

The Fakahatchee Strand is a 20-mile-long and 3- to 5-mile-wide major drainage slough of Big Cypress Swamp. It contains the largest stand of native royal palms and largest concentration and variety of tree orchids in North America, as well as a number of other plants that are extremely rare. It's believed that the unique forest of cypress trees and royal palms may be the only one in existence in the world.

Coastal prairies can be found in Everglades National Park behind the beaches of Cape Sable and behind the mangroves that line the northern edge of Florida Bay. The open prairies are low, flat lands that have been formed and are maintained by passing hurricanes and tropical storms that carry salt water and marl (a limey mud) miles inland from Florida Bay.

Only low-growing desertlike succulents and cacti are capable of survival in these dry, salty conditions. Common plants are the multichambered glasswort (Salicornia birginica), sea oxeye daisy (Borrichia frutescens), saltwort (Batis maritima), also known as pickle weed; and prickly pear cactus (Opuntia stricta).

Marsh hawks (also known as northern harriers) (Circus cyaneus) and red-shouldered hawks commonly hunt over the coastal prairies. Marsh hawks are easy to spot because of their kite-like ability to glide on wind currents low to the ground. The rare Cape Sable seaside sparrow (Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis) also inhabits these prairies. This 6-inch-long, greenish-colored endangered species is a member of the American Sparrow subfamily. Rarely seen, it is hard for even trained bird watchers to spot.

The most distinguishing feature of the Everglades, and that for which it was named, is a wide, shallow marshy river that was brought to the world's attention in Marjory Stoneman Douglas's groundbreaking book, The Everglades: River of Grass. Forty to 50 miles wide, and only inches deep, the historic river of grass originated as water flowing out of the southern end of Lake Okeechobee and across the nearly flat prairies at an almost imperceptible rate of no more than 100 feet per day. Sawgrass (Cladium jamaicense) is the dominate species growing profusely across this vast wilderness, which is also interspersed with torpedo-shaped tree islands and the rounded domes of cypress heads. The land is so flat, dropping only 2 or 3 inches per mile, that changes in elevation of only inches result in entirely different and distinct habitats and landscapes each with their own community of plants and animals.

Freshwater sloughs are the deeper and faster-flowing centers of a broad, marshy river. Everglades National Park contains two distinct sloughs (pronounced "slew"), the Shark Valley Slough, which is the true "river of grass," and Taylor Slough, a narrow eastern branch of the "river."

Common mammals found in the sloughs include river otters (Lutra canadensis), which are very active and well adapted to aquatic life. They can often be seen playing or hunting for food in the open freshwater areas. Their permanent dens are often dug into mud banks and have both an underwater and an exposed entrance.

Another unusual aquatic creature is the marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris), which uses its large feet to cross wet, muddy marshes and to swim in deep water. The rabbit can be seen along roadsides near freshwater lakes and marshy areas. When threatened the marsh rabbit takes to the water where it can float with only its eyes and nose exposed.

Several species of freshwater fish are found in sluggish streams and swamps. Common species include largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), black crappie (Pomoxis nigomaculatus), Mozambique tilapia (Tilapia mossambica), chain pickerel (Esox niger), and redbreast sunfish (Lepomis auritus).

The Eastern mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), a member of the Live-bearer family, is a small but important player in the ecology of the Everglades. About 1.5 inches long, the olive brown fish lives in ponds, lakes, drainage ditches, and brackish waters, where it feeds greedily on hordes of mosquito larvae that begin life underwater. In accordance with nature's plan, mosquitofish, which reproduce by the thousands during rainy seasons, are a mainstay in the diets of numerous birds, mammals, and reptiles throughout the region.

In estuaries such as Florida Bay, all the right ingredients, salt water and fresh water, nutrients from soil and decaying plants, and sunlight, come together to give rise to some of the most productive habitats in the world.

Wedged between the Florida Keys and the Everglades, and situated entirely within Everglades National Park, Florida Bay is a triangularshaped body of water covering an area of 400,000 to 550,000 acres, depending on where the western boundary with the Gulf of Mexico is measured. Its waters are dotted with 237 mangrove islands. Sea turtles, dolphins, game fish, and a unique mix of bird life rely on the bay for food and in some cases nesting sites.

The bay's productivity depends upon a bountiful underwater "forest" of turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum). The most common seagrass in the bay, turtle grass continues to survive despite problems with the bay's salinity. Other less-tolerant types of seagrass have died back due to changes in the natural plumbing system of the Everglades.

Under natural conditions, the bay received enough fresh water from the Everglades to maintain a brackish water estuary. In more recent times, the bay has suffered from a periodic lack of freshwater inflow, which has caused the massive die-off of hundreds of acres of valuable seagrass habitat.

On the southwestern coast, the Ten Thousand Islands mangrove-dominated estuary is the final destination for the vast amounts of water flowing through the Big Cypress Swamp. Often described as the Florida equivalent of a tropical rain forest, the whole life-propelling estuary system actually begins with the mangrove trees, which act as solar panels for the estuary.

Powered by the sun, they capture and store energy. As the trees grow, older leaves turn yellow and drop into the water, sending energy into the system. The leaves are colonized by algae and fungi and then either decay or are eaten by small crabs, snails, and fish—initiating the tropical food chain. More than 3 tons of leaves can fall from a single acre of mangroves every year.

Many of Florida's estuaries are popular with sport-fishermen. Among the more sought after species are redfish (Sciaenops ocellatus), which are also know as red drum. Bronze colored with white undersides, redfish always have one or more prominent ringed spots on their sides. Known as tough competitors with a good food value, redfish are highly prized by anglers. Although reaching weights of more than 90 pounds, redfish in the 10 pound range are commonly caught in the estuary waters around South Florida.

Another popular species is spotted seatrout (Cynoscion nebulosus), one of Florida's most common game fish. It is caught throughout the coastal waters of the Gulf and Atlantic, but rarely in the Lower Keys. It has a silver body with black spots, but the fish becomes darker when it lives in back bays or inland creeks. The species can reach weights of 10 to 15 pounds, but most spotted seatrout that are caught weigh 2 to 3 pounds.

Tarpon (Megalops atlanticus) is another popular and protected game fish. Olive-gray and silvery colored, tarpon can reach lengths of 4 to 6 feet and weights up to 200 pounds. Its favorite habitats are open seas, shallow coastal waters, and estuaries. Snook (Centropomus undecimalis) is also one of South Florida's premier game fish. Silver colored, with a distinctive black line running down its side, snook are caught in mangrove estuaries and inland brackish-water rivers and creeks. Also called "linesides," they can reach weights of 50 pounds but average much smaller.

The South Florida region also sports some of the most attractive beaches in the world. The beach at Bahia Honda State Park, with its long strands of soft, white sand bordered by swaying palm trees, is without question the best beach in the Keys, and is often rated as one of the best in the nation. On the southwestern coast, the Naples area has more than 40 miles of beaches accessible at various points. Most are heavily visited and have varying levels of facilities (see Naples Area Beaches, page 264). Some of the Naples beaches also rank among the best in the nation.

The 10 miles of bright white, isolated beaches on Cape Sable in Everglades

National Park are among the few wild beaches left in Florida. They can only

be reached by a 15-mile boat trip. The whiteness of a beach is determined by

how much of the sand is composed of crushed seashells and how much of crushed

rock. On Cape Sable, the pure white beaches are made almost entirely of shell.

Sea purslane (Sesuvium portulacastrum) and sea oats (Uniola paniculata) are two of the plants that are able to brave the harsh conditions at the top of the beach and anchor the soft ground. The long roots of the sea oat help to secure dunes against wind and storm. The seeds and the plants are protected from harvest by state law. Sea oats have narrow, pale green leaves and a prominent 3-foot stem displaying a thick seed head that waves in the wind like a small flag. The individual seeds look like oats.

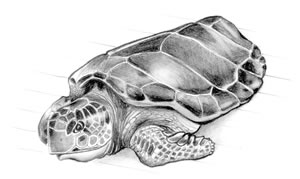

Florida's beaches are also very important as nesting sites for many of the world's sea turtles. Sea turtles mate in shallow waters close to nesting beaches. From early spring to mid-September, females come on shore after dark and lay eggs in holes they dig above the high tide line. They deposit anywhere from 40 to 180 eggs, which are covered with sand. The eggs are warmed by the sand and sun, and several weeks later the young break out of their shells at the same time and dig their way to the surface. From there they follow their instincts across the sand toward the slighter brighter horizon over the sea. Many perish on the way, eaten by birds, raccoons, crabs, and other predators lying in wait for the slowly moving feast. Street lights and other artificial lights attract some baby turtles inland, away from the water.

Those that reach the comparative safety of the water are often eaten by fish and diving birds. The few that miraculously reach maturity will some day follow an inner compass back to their birthing beach, where they will continue the turtles' uphill battle against extinction.

Loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta), which are classified as a threatened species, are some of the most commonly encountered sea turtles in South Florida waters. Maturing at up to 3 to 4 feet in length, they're dark reddish brown and have a large head and pointed beak. They make their home in bays, estuaries, and the open ocean. The endangered green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) has a large head and olive-green scales. It nests mainly on the Atlantic coast of Florida between Palm Beach and Cape Canaveral. Although once common in South Florida waters, it suffered from overharvest for use as food and to make cosmetic oils, and it is now rarely seen as far south as the Keys. The endangered Atlantic hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) and the endangered Atlantic ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempi) are occasionally seen in the clear waters in Florida Bay, Dry Tortugas National Park, and Biscayne National Park.

The numerous and distinctive habitats found in the Everglades and Florida Keys support a variety of endangered and threatened wildlife. Some species, like the Florida panther (Felis concolor coryi) or the wood stork (Mycteria americana), move freely between various habitats. While others, like the Florida tree snail or the Cape Sable seaside sparrow (Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis), are restricted to small niches in the ecosystem.

In fact, many of the 74 federally endangered plants and animals found in Florida, the most in any state except California and Hawaii, are found within South Florida coastal habitats. This unfortunate list includes the American crocodile, the Atlantic green sea turtle, Atlantic ridley sea turtle, leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), red-cockaded woodpecker (Picoides borealis), Cape Sable seaside sparrow, Key deer, snail kite (Rostrhamus sociabilis), Key Largo wood rat (Neotoma floridana smalli), Queen conch (Strombus gigas), Schaus' swallowtail butterfly, West Indian manatee (Tricechus manatus), and Florida panther. Threatened species include the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), loggerhead sea turtle, southern bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocoephalus leucocephalus), peregrine falcon (Falcon peregrinus), and roseate tern (Sterna dougallii).

Florida's standing among states with high numbers of endangered species is due in part to the unique habitats that are found nowhere else in the continental United States, and to the overall distribution of many of the listed species. Like many states, Florida contains remnant populations of species that have been eliminated elsewhere. The Florida panther, for example, was once found throughout the Southeast, but now only exists in South Florida.

A number of other endangered species, however, such as the West Indian manatee, American crocodile, and snail kite, exist in Florida at the very edge of their natural range and are still found in the West Indies and South America. Yet another group of endangered species, which includes the Schaus' swallowtail butterfly, the Florida tree snail, and the Cape Sable seaside sparrow, are endemic to specific habitats (in this case tropical hardwood hammocks and coastal prairies) and have always only existed in small and fragile populations.

Following is a detailed description of five threatened and endangered species. For more information on endangered species in Florida, contact the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (see Appendix C). Contact information is provided in the glossary of this book.

Florida panthers are very rarely seen by anyone other than the scientists who keep track of them with radio collars. Before European settlement, the big cats roamed all of Florida. Primarily out of fear for themselves and their livestock, early settlers actively tried to rid the state of these elusive creatures. Bounty laws in the nineteenth century granted a cash payment for panther hides even though there are no documented reports of Florida panther attacks on humans.

In the l950s and l960s, destruction of the panthers' habitat for urban and agricultural development severely reduced their living space, and the panther population dwindled dangerously low. The Florida panther was placed on the federal endangered species list in 1967. In 1979, the State of Florida made it a felony, with a five-year prison sentence, to kill a panther. Somewhere between 40 and 70 of the majestic cats remain in the wild.

Even with the best efforts of state and federal biologists, dwindling habitat and road kills continue to take their toll on the species. Underpasses have been installed beneath some highways to provide safe passage for the cats, which can roam up to hundreds of square miles.

Despite its name, the Florida panther is not a close relative of panthers that live in Africa and Asia. It's actually a subspecies of the western cougar or mountain lion. Adult males mature at up to 8 feet from tail to nose and weigh 110 to 125 pounds. Females average about 6 to 7 feet and weight 75 to 85 pounds. The Florida panther has a short, tawny-brown or golden coat, a long tail, long legs, and wide paws with retractable claws. The panther doesn't roar; instead it purrs, screams, and hisses, similar to a house cat only with a chillingly high increase in volume.

In pursuit of prey, a Florida panther can run for short distances at 30 to 35 miles an hour. Acute senses of smell and hearing also aid in the hunt. White-tailed deer and wild hogs are the mainstays of its diet, which it supplements with birds, rabbits, armadillos, rodents, and even small alligators.

Mainly nocturnal, panthers spend the daylight hours resting in hardwood hammocks, swamps, and pine forests. They are typically solitary creatures, and adult males hardly ever share the same territory. Litters are usually born in the spring with the female giving birth to between two and four cubs. She nurses them for about eight weeks, until they are ready for their first fresh meat.

The female stays with her cubs for about two years, teaching them hunting skills and survival techniques. When she is ready to find another mate, the cubs are pushed out on their own. Only a small number survive to adulthood.

Manatees aren't particularly graceful or photogenic or adept at performing and interacting with humans. They just go on about their grazing oblivious to most interruptions. Manatees have a bulbous, grayish-black, seal-like body that tapers to a flat, paddle-shaped tail. A pair of small front flippers propels them slowly through fresh, brackish, and shallow ocean waters. Vegetarians, they feed exclusively on seagrasses, water hyacinths, and other water plants. Every few minutes they rise to the surface for air.

Commonly known as sea cows, full-grown West Indian manatees average 8 to 10 feet and weigh 1,800 to 2,500 pounds. Among the most beloved of Florida's wildlife, manatees are protected by state and federal law as an endangered species. A specialty license tag is sold by the State of Florida to raise money for their protection. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that about 2,300 now live in Florida.

Docile, with no defense mechanisms, the species is distantly related to elephants. Both sides of manatees' split upper lip grasp vegetation and roll it into their mouth, similar to the way an elephant uses its trunk to gather food.

Manatees' gentle nature has also contributed to their endangerment. Many are killed every year in boat locks, and through collisions with power boats and even barges, which sometimes trap the animals beneath their wide hulls. During the 1990s hundreds of manatees also fell victim to a massive outbreak of red tide (a toxic algal bloom) that appeared on the southwestern coast of Florida.

Manatees communicate with high-pitched squeaks and chirps, similar to dolphins. Females give birth to a single calf about every two to three years, and nurse for about two years. They closely protect their young and remain with them for at least two years.

In summer, manatees travel in small groups as far north as the coasts of Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia. They have a low tolerance for water colder than about 65 degrees Fahrenheit, and in winter they migrate to warm springs in coastal Florida and more southerly habitats in the Keys.

American alligators were once nearly wiped out for their hides and meat but have since made an exceptional comeback across Florida. Only a few thousand remained 25 years ago, but the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimates the state's alligator population is now more than 1 million. Although alligators are no longer on the endangered species list, they remain under federal protection on the threatened species list.

During the late spring breeding season, female alligators construct 4-foot-tall pyramid-shaped mounds of mud, reeds, twigs, grass, and other vegetation as nests for laying their eggs. Several dozen hard-shelled, leathery eggs are laid in the center of the mound. During the nine-week incubation period, the decaying vegetation and hot sun keep the interior of the nest warm, while the mother remains on constant vigil against birds, raccoons, and other potential predators.

The eggs begin to hatch in late summer and the young claw their way out of the shells. Alerted by the chirping of her hatchlings, the mother digs them out of the nest and carries them to the water in her mouth. At birth, alligators are about 8 inches long and weigh about 2 ounces. They grow about 1 foot per year for the first five years. Those that survive for a year reach 18 inches and 10 ounces. At 30 years, a male can attain 12 to 13 feet and weigh as much as 850 pounds.

Adult alligators have huge, incredibly strong jaws, 80 strong teeth, and a brain about the size of a walnut. When the jaws are closed, only teeth of the upper jaw are visible. Eyes, ears, and nostrils are on the top of the head, enabling alligators to see, hear, and smell when swimming just beneath the surface with the tops of their heads exposed.

When an alligator submerges, a series of natural mechanisms are triggered. The throat closes so the alligator can grab prey without taking water into the lungs. Flaps of skin close the outside ear openings and protect the eardrums. Nostrils close, and a thin, soft, third eyelid protects the eyes from water and allows the alligator to see as well underwater as it does on the surface.

Alligators are usually docile but can be dangerous to humans who surprise them or come too close to their nests. They are unpredictable and never should be approached. On land they can run incredibly fast for short distances. By nature, alligators fear adult humans and prefer to hunt smaller prey, such as birds, raccoons, fish, and crabs. Nevertheless, wading into murky water or swimming at night where alligators are known to reside carries obvious risks. Special care should be taken with small children and pets, which are more the size of an alligator's natural prey. Dogs swimming in canals and ponds, or straying too close to shorelines often become alligator victims.

Nine people have been killed in gator attacks in Florida, about half of them children, since 1972. The state averages about 4 to 5 serious bites every year, and about the same number of minor bites. With more than 1 million alligators and a human population of more than 15 million, Florida officials say that makes the odds of being bitten less than being struck by lightning.

A small, endangered population of American crocodiles exists in the Upper Keys and Florida Bay area. The American saltwater crocodile is one of the least aggressive members of the world's Crocodile family. Shy and reclusive, it avoids all contact with humans.

The American crocodile is broadly distributed along the coastal and estuarine shores of the Caribbean, including the coasts of Venezuela, Colombia, Central America, and Mexico. In Florida, American crocodiles were once found from Lake Worth (near West Palm Beach) down the southeastern coast to Key Largo and across the northern shore of Florida Bay to Cape Sable.

Scientists estimate that the number of American crocodiles in Florida is 600 or less. Only about 50 of those are mating pairs. The population is centered around northeastern Florida Bay and Key Largo.

Crocodiles are distinguished from broad-snouted, darker-colored alligators by their grayish-olive green color and their long, tapered snouts. They also have a long, pointed tooth near the front on each side of the lower jaw that remains exposed even when the mouth is closed. Their large mouths and huge, tearing teeth enable them to capture snakes, turtles, fish, birds, raccoons, and rabbits. They can go for long periods without eating. They store up heat by lying in the sun. Adult crocodiles can measure up to 12 feet in length. The largest ever recorded in Florida was nearly 16 feet.

Mating takes place in March and April, and in early summer, female crocodiles lay their eggs in a mud or sand nest in brackish or salt water along canal and creek banks and away from the vegetation line of Florida Bay. They lay an average of 30 to 50 eggs, and incubation takes 80 to 90 days. Females remain near the nest but don't protect the nest as zealously as female alligators.

When the young are born, they measure about 10 inches long. The mother crocodile digs them out of the nest and carries them to the water in her mouth, then abandons them. The young stay together for about a month for mutual protection. Some find their way to muddy water holes, where they feed on small snakes, fish, and insects.

Also known as pink conch, the queen conch is a marine snail that is a victim of its own beauty. The large, spindle-shaped shell, with the lustrous, flaring pink lip, is a prized souvenir that thousands of tourists take home as a reminder of the Florida Keys' stunning beauty. Lovely to look at, conchs are also delightful to eat. Their tasty meat has been a mainstay of Keys and Caribbean residents for hundreds of years. Conch fritters, conch chowder, and conch salads are popular restaurant fare. They were once so plentiful, they could be gathered up by the bucketful in beaches and shallow waters.

Overaggressive harvesting has severely decimated their numbers. In 1985, the State of Florida put them on the protected species list. The conch meat and shells sold in restaurants and stores throughout the Keys is imported legally from other countries.

Queen conch mating takes place between February and October. Females lay their eggs on sandy sea bottoms in depths ranging from a few feet near shore to more than 400 feet.

Females lay their eggs three weeks after mating and can produce five to eight egg masses a season. Each egg mass, looking like a mound of soggy cooked noodles, contains up to 500,000 eggs, which hatch in three to five days into microscopic larvae. The young conchs then drift through the sea currents, feeding on single-cell plants. In another month those few that survive settle to the sea bottom and metamorphose into bottom-feeding snails about the size of a grain of sand. Those that survive for three years reach their full size of 9 to 10 inches. Their many predators include sharks, octopuses, sea turtles, and humans.

"We observed great flocks of wading birds flying overhead towards their evening roost...they appeared in such numbers to actually block out the light for some time."

— John James Audubon, Remembrances of a Trip to South Florida, circa 1832.

Birds of the Everglades and Florida Keys deserve a special mention. From backyard feeders to tropical hardwood hammocks in the Everglades wilderness, from roadside canals to isolated keys far from land, bird life in the Keys and Everglades is both startling and commonplace.

What Audubon witnessed in 1832 was one of the greatest wildlife spectacles ever known—millions of wading birds nesting and feeding in Florida's wetlands. By 1900 these flocks had been hunted down to near extinction for their beautiful feathers. Legal protection passed in 1905 partially restored the birds' numbers, but ongoing draining of the Everglades combined with extensive habitat loss has resulted in a 90 percent decline in their historic, overall numbers.

Nevertheless, birds and bird watchers are still a constant part of the landscape of coastal South Florida. Following are a few of the more interesting species you're likely to encounter, but there are literally hundreds or others waiting to be discovered by the veteran birder or the casual observer. Don't forget your binoculars!

Brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis). This marine bird dives head first into the water using its huge throat pouch as a dip net to catch fish. Brown pelicans have special air sacs beneath their chests to cushion the impact as they hit the water. During the summer brown pelicans nest in mangrove areas.

Great white heron (Ardea herodias). The largest of all herons, the great white has brilliant white plumage and light colored legs, which differentiate it from the similar-looking, black-legged great egret (Casmerodius albus). A color variation of the great blue heron (Ardea herodias), it is frequently seen in and around Florida Bay where it stalks a variety of large prey including rodents and other birds.

Osprey (Pandion haliaetus). This hawk is well adapted to catch the fish that make up its diet. The soles of the osprey's feet have sharp projections that help it grip its slippery prey. It hovers until spotting a fish near the surface, then it suddenly plunges feet first into the water, grasping the fish in its talons. Osprey are a frequent sight throughout the Keys and the Everglades. Their nests can often be see on the top of electrical poles and in tall trees.

Peregrine falcon (Falcon peregrinus). Like the bald eagle, the population of this small, powerful, threatened raptor is increasing since the use of the pesticide DDT has been discontinued. With a raucous "kak kak" cry, the peregrine falcon patrols the skies for sick and slow-flying birds and dives to the ground for mice and other small animals. It is a frequent sight in Florida's marshes and coastal areas during fall migrations.

Pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus). Despite its large size, this elegant black and white woodpecker with a bright red crest is adept at keeping out of sight. In the Everglades it often builds its nest in the trunk of a palm tree. You can hear its strong and loud drumming on trees from a great distance and sometimes spot its fast, undulating wing beat as it flies from tree trunk to tree trunk.

Piping plover (Charadrius melodus). This diminutive, gray and white, 7-inch to 8-inch bird is a member of the Plover family and is on the threatened species list. With a short black bill and "peep-lo" call, it can be sighted in sandy flats and coastal areas.

Purple gallinule (Porphyrula martinica). This striking green and purple bird can be seen in freshwater sloughs and ponds in the Everglades walking gingerly on spatterdock leaves using its very long toes to lift the leaves in search of insects. The gallinule's long toes also enable it to climb low bushes. When walking or swimming it constantly jerks its head and tail.

Roseate spoonbill (Ajaia ajaja). This is a species of special concern in Florida, and the number of roseate spoonbill breeding pairs is estimated at only about 500. The striking pink and white wading birds feed in shallow water by moving their beaks from side to side, catching small fish, crustaceans, and insects. Their primary nesting areas are mangrove islands in Florida Bay, which they share with other wading bird species.

Snail kite (also known as Everglades kite) (Rostrhamus sociabilis). An endangered member of the same family as hawks and eagles, snail kites feed almost entirely on Florida apple snails, which they extract from the shell with their sharply hooked beaks. Destruction of freshwater marsh habitats has reduced this once abundant species to only a few hundred, placing it in grave peril of total extinction.

Southern bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocoephalus leucocephalus). While it remains on the threatened species list, this magnificent national symbol has been making a comeback since being placed under federal protection. Hundreds of nesting pairs now exist throughout Florida. It is often seen perching near coastal and inland waterways.

Tricolored heron (Egretta tricolor). This small, blue and gray heron walks quietly through still water to stir up prey, or stands motionless waiting for prey to swim within reach of its long neck and quick beak. Sometimes it extends its wings to cast a shadow across the water to make the prey below the surface more visible.

White-crowned pigeon (Columba leucocephala). A threatened species, the white-crowned pigeon is found only in the southern portion of Everglades National Park, the Keys, and neighboring Caribbean islands. It breeds in summer on islands in Florida Bay, where it feeds on the fruit of tropical hammock trees.

White pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos). Flocks of these majestic white migrants with distinctive black wing tips fill the sky each winter, forming long lines and flapping their enormous wings in unison. They fish in formation as well, swimming on the surface and using their wings to drive their prey into shallow water where they seize the fish in their large pouched bills.

Wood stork (also known as wood ibis) (Mycteria americana). The wood stork is the only member of the Stork family that can be found in the United States. On the endangered species list, the tall bird is clumsy looking on land but graceful in flight. With white feathers and long, skinny black legs, wood storks stand about 3.5 feet high, with a wingspread of 5.5 feet. They nest together in large colonies and feed by stalking patiently through muddy water with their beaks submerged, ready to grab and immediately swallow anything that comes within range.

South Florida's first human inhabitants may have arrived as early as 10,000 years ago. They lived in an arid climate on a flat land that held little surface water, and they hunted Paleolithic megafauna like bison and mammoths. Around 5,000 years ago, as a result of a changing climate, melting glaciers, and a rising sea level, a subtropical terrain began to form composed of islands, cypress swamps, hardwood forests, and sawgrass prairies. The large animals disappeared, and the inhabitants responded by establishing other patterns of subsistence.

The descendants of these early arrivals, the Tequesta Indians on the southeastern coast and Calusa Indians on the southwest, built their villages at the mouths of rivers, on offshore islands, and on elevated pockets of tropical forest. They turned their hunting skills to smaller reptiles and mammals and they took to the sea to catch fish and harvest shellfish.

There are accounts of Tequesta Indians who, when they spotted a pod of whales offshore in the Atlantic, would paddle after them in canoes. When a whale surfaced within range, an Indian would leap aboard its back and plug the animal's breathing hole with a stake. After the whale suffocated, it was hauled to shore. The North Atlantic right whale may have been the most common species taken this way.

The Calusa on the southwestern coast used huge dugout canoes that held as many as 40 paddlers. As the Indians expanded their realm of influence, the big canoes were used for carrying trade goods through the Gulf and Caribbean. The Calusa also built huge shell mounds, as large as 40 acres, throughout the Ten Thousand Islands.

The Calusa Indians are known to have had a highly evolved political structure and are believed to have dominated the Tequesta and other tribes, including the Jeaga and Ais who lived on the Florida east coast north of the Tequesta, and the Mayaimi, who lived in the interior near Lake Okeechobee.

In 1896, Smithsonian archeologist Frank Hamilton Cushing excavated a Calusa Indian shell mound on Marco Island and discovered tools, weapons, utensils, wooden ceremonial masks, and wood carvings including heads of animals such as a wolf, sea turtle, pelican, and alligator. The most famous artifact uncovered is known today as the Marco Cat—a breathtaking, fully preserved wooden statuette of a panther 6 inches in height that was carved from a "gnarled block of fine, dark brown wood." Cushing speculated it had either been "saturated with some kind of varnish, or more probably had been frequently anointed with the fat of slain animals or victims. To this, doubtless, its remarkable preservation was due."

The article that most fascinated Cushing, however, was a wooden deer head. He wrote: "This represents the finest and most perfectly preserved example of combined carving and painting that we found…it portrayed with startling fidelity and delicacy, the head of a young deer or doe…The muzzle, nostrils, and especially the exquisitely modeled and painted lower jaw, were so delicately idealized that it was evident the primitive artist who fashioned this masterpiece loved, with both ardor and reverence, the animal he was portraying…"

Spanish explorers are believed to be the first Europeans to see the Florida Peninsula. Estimates place the number of Indians occupying South Florida when the Spanish arrived to be 20,000 with perhaps 100,000 living throughout the state.

On April 2, 1513, Don Juan Ponce de Leon made landfall near present-day St. Augustine. He christened the land La Florida, in deference to the Easter season, which Spaniards called the Feast of Flowers. The 53-year-old was not really seeking a fountain of youth. The hardened soldier and explorer, in fact, was seeking new lands for his king and country, and gold and glory for himself.

As the Spanish sought to establish forts and religious missions in La Florida, and slave traders raided Indian villages, the Tequestas and Calusas grew increasingly unfriendly. In 1521, Ponce de Leon and 200 Spanish soldiers were ambushed by a large force of Calusas at Charlotte Harbor, near present-day Fort Myers. Ponce de Leon was struck in the chest by an arrow believed to have been dipped in the poisonous sap of the manchineel tree. He was taken to Cuba, where he died and was buried.

Undeterred, the Spaniards fortified their hold on the New World. On August 28, 1565, the feast day of Saint Augustine, ground was blessed in northeastern Florida for what is still the oldest continuous settlement in the United States, St. Augustine.

Less than 200 years later, decimated by their wars with the Spanish and English, by constant slave trader raids, and by European diseases such as typhus, measles, yellow fever, and smallpox, the Calusas and Tequestas had become virtually wiped out. By 1763, when Spain ceded Florida to the British as part of the treaty ending the Seven Years War, the few remaining native peoples were reported to have migrated to Cuba with the Spanish.

In their place came bands of Creek Indians, who migrated south from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Alabama ahead of European expansion. Collectively known as Seminoles, they lived and hunted throughout the state and provided refuge for runaway slaves. When Congress ordered all Native Americans east of the Mississippi River to move to present-day Oklahoma in 1830, many of these Indians resisted and fought three wars with the U.S. Army.

Although harassed and hounded for decades, a small group of Indians, sometimes estimated at about 300, simply refused to surrender, eventually taking refuge in the Big Cypress Swamp and the Everglades. From these strong and proud people have come the Seminole and Miccosukee people that live in South Florida today.

The Miccosukee, who were originally known as Mikasuki and who spoke the Hitichi language, were given tribal status in 1962 following an international campaign that was supported by Fidel Castro, who among other international leaders at that time recognized the Indians' nationhood.

Today the Miccosukee occupy a reservation straddling Interstate 75, with a small tribal headquarters area along the Tamiami Trail (Highway 41), next to Everglades National Park. The Seminoles, who spoke the Muskogee language, occupy four reservations, with the largest (69,900 acres) located in the Big Cypress Swamp.

Following statehood in 1845, and the end of the Indian conflicts in 1856, South Florida became the target of northern tycoons and would-be land barons who sought to gain wealth from the lands' natural resources. Since large areas of the state were periodically under water, great schemes were developed to drain the swamps and the Everglades—schemes that continued until the latter half of the twentieth century.

Hamilton Disston, a wealthy young man from Philadelphia who inherited his role as the country's largest manufacturer of saws and files, initiated the first broad plans to drain the Everglades in 1877. Rivers were straightened where possible, natural limestone barriers were blown away, and canals were dredged to carry the unwanted water to the sea (see The Florida Everglades, page 153).

An era of steamboat traffic that had begun early in the nineteenth century reached its peak during the later part of that century as more waterways were opened. By 1880 railroads were being pushed down both the east and west coasts and settlement quickly followed.

On the east coast, in the late 1880s, Henry Morrison Flagler, a wealthy Standard Oil executive, purchased a small North Florida railroad. In St. Augustine and other Florida cities, he began building resort hotels that he hoped would entice affluent northerners to visit and subsequently invest in the state.

In 1896, Flagler completed his Florida East Coast Railroad to Miami. The extension was part of an agreement with Mrs. Julia Tuttle, who offered him half her property in the small, unincorporated community of Miami, if he would complete the railroad, map out a town, and build a hotel worthy of upper class guests. Flagler carried out the plan, and Miami was incorporated in July 1896.

Flagler continued to pursue a dream of extending his railroad all the way to Key West, a feat he achieved in 1912 just prior to his death the following year (see Florida Keys, page 27).

On the west coast, Barron G. Collier, a wealthy advertising executive, had purchased more than 1 million acres in what would become Collier County. He brought the railroad south to Everglades City and initiated the completion of the Tamiami Trail (see Western Everglades, page 223).

Florida's population growth, although beginning slowly following statehood in 1845, would eventually come to threaten every major habitat and body of water in South Florida. A federal census taken during the territorial period (1821_1845) showed a mere 34,000 residents within the state. Most of the population was centered in St. Augustine on the northeast coast, Pensacola on the western end of the Panhandle, and Tallahassee right in the middle of the state. Cotton farming, commercial fishing, and timber harvesting were the dominant industries.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Florida had acquired more than half a million inhabitants. Jacksonville, a port city on the northeast coast near the Florida/Georgia border, was the largest city with 23,000 inhabitants. But on the heels of newly drained land and rapid railroad expansion down both coasts, growth patterns were quickly changing in favor of South Florida.

By 1930 the state's population had reached 1.5 million residents, and the beginnings of large metropolitan areas were developing around Miami on the southeastern coast and around Tampa and St. Petersburg on the central west coast. Following World War II, a developing tourism industry combined with rapidly expanding retirement communities initiated an explosion in population that changed the face of the state.

Huge expanses of wetlands were rapidly transformed into farming, ranching, and residential communities. The majority of urban development took place at first along the Atlantic coastal ridge in southeastern Florida where Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties, with a combined estimated population of 4.5 million, still make up one of the fastest growing areas in the country.

As development continued in southeastern Florida, it pushed west into the Everglades, draining the land and pushing the wilderness farther and farther away. On the southwestern coast, urban sprawl in the Naples area created a more recent struggle over protecting that area's unique habitats that continues today (see Naples, page 261).

Averaging 9,000 new residents arriving per week during the latter part of the twentieth century, Florida's population continues to grow. By the beginning of 1999, the state was home to an estimated 15 million residents, four-fifths of whom reside along the coasts. That number swells annually with the arrival of more than 40 million tourists.

Fortunately, millions of acres of South Florida's native habitats survived and are protected within a vast network of public lands including Everglades National Park, Biscayne National Park, Big Cypress National Preserve, Dry Tortugas National Park, and dozens of other state and federal refuges, parks, recreation areas, marine sanctuaries, and wildlife management areas described in this book.

So when you visit the Keys and the Everglades, and you should, please remember that despite the unbridled growth and mounting pressure on the natural resources, most Floridians are proud of their state and their relationship to the land and its wildlife. With public support, the State of Florida has already purchased more than 1 million acres of fragile lands for preservation. In 1998, Florida voters passed a constitutional amendment by a 72 percent majority that provided a permanent funding source to continue purchasing and protecting important wildlife habitat.

Floridians have also learned that with wildlife so close, it has to be respected. Alligators in swimming pools are common, as are deer in backyards, wading birds in roadside ditches, spiraling flocks of white pelicans over coastal condominiums, and beaches used by people in the daytime and nesting turtles at night.

South Florida is also a place accustomed to visitors, so there are many attractions, both natural and man-made, that will vie for your attention. But while you're here take at least one long walk along a beach, exploring for tiny treasures in the line of shells thrown up by the waves. Go swimming at least once in the salt water, and eat in a restaurant that serves real Key lime pie. Sample a platter of seafood, and maybe try something a little different like gator tail, Florida lobster, frog legs, cracked conch, or Indian fry bread. Try not to miss a sunset, and catch at least one sunrise over the water or the grassy plain of the Everglades; you'll never forget it.

Please be careful with the fragile land and fragile wildlife. Note the signs protecting turtle nests and bird rookeries. Follow the boating rules to protect manatees, fragile seagrass, and coral reefs, and watch for wildlife on the roads when traveling anywhere in the Keys or Everglades.

All that's left is to bring your camera and your sunscreen, wear your hat and sunglasses, and have fun. You'll discover a land that is as unique and enchanting as any on earth.