It's only a 48-mile drive from Homestead to Flamingo, at the very tip of mainland Florida in Everglades National Park, but the trip takes you from a fast-paced urban environment of concrete and traffic lights, to a serene, yet wild land called the Everglades. Along the way you'll be treated to a number of astonishing points of interest.

The road passes through a land like none other in the world. This is a place where time, weather, geography, fire, and water have created a varied landscape—some of which man has altered, and some of which man is trying desperately to repair.

A number of stops along the road in Everglades National Park have been made accessible to the average visitor by the National Park Service. There are well-constructed trails and boardwalks that pass through dark, primitive hammocks and cross wildlife-filled sloughs and sawgrass prairies. Roadside ponds and overlooks provide exciting opportunities for wildlife viewing. Each stop reveals a different habitat and a different connection to the overall Everglades ecosystem."

But the park experience will not always come to your car. You should get out and take a closer look, listen a little more carefully, and maybe walk a little farther. If you do, you'll see enough to come away with a steadfast appreciation for this unique and intricate ecosystem.

[Fig. 12] From the end of the Florida Turnpike, the road to Everglades National Park (SR 9336) heads west than south, passing first through Florida City, a small agricultural community. Watch for Roberts Fruit Stand just outside of Florida City. It's a great place to sample locally grown tropical fruits, including sapodilla, egg fruit, papaya, limes, and oranges that you might want to add to your picnic cooler.

Heading south on SR 9336 (SW 192 Avenue), the signs you'll see for airboat rides are part of a commercial operation on the edge of the park called Everglades Alligator Farm. Located 4 miles south of SW 344th Street on SW 192 Avenue, it features airboat rides, alligator and nonpoisonous snake demonstrations, wildlife lectures, and a gator farm.

During a walk around the alligator pen, only a chainlink fence separates you from hundreds of the big brutes. In addition, the wildlife lectures sometimes include captive black bears, bobcats, and even Florida panthers that have been injured and rehabilitated but cannot be returned to the wild because the permanent disabilities they suffered would prevent them from surviving.

Continuing toward the park you'll begin passing through the middle of a widespread farming district. Known as the Rocky Glades, the dusty white and rocky fields belie their nonfertile appearance with bountiful crops of green beans, peppers, and lots of tomatoes. Often long strips of plastic are used as mulch in these intensely farmed lands and there's not a weed in sight.

And then without warning there's a nearly instant transition from monocultured farmland, to the multihabitat, multispecies land of the Everglades. All of a sudden the wildlife outnumbers people and cars, and the glare of the bright, treeless farmland is replaced by a restful scene of green and yellow pastels. You've entered Everglades National Park.

[Fig. 10] The first thing you may notice upon entering the park is the hundreds of pine trees that have been broken off 15 to 20 feet above the ground. This is the first evidence you'll see of the passing of Hurricane Andrew, but not the last. Fortunately, in even the most damaged pineland areas, only about 35 to 40 percent of the trees were felled.

Forests of South Florida slash pines, similar to what you see here, once covered all the limestone ridges of southeastern Florida. Since they tend to grow on high ground, the pines covered the most desired building sites and were the first to go when the building boom hit South Florida in the 1940s and 1950s. Before that logging took a heavy toll; even in the park most of the pine trees are second growth.

You'll also soon begin passing through the first of many sections of sawgrass prairies. The golden-green grass extends on the flat land as far as the horizon, interspersed with only the rounded domes of tree hammocks. The scattered, spidery white flowers of the water-loving swamp lily (Crinum americanum) are easy to spot when it is in bloom.

Also, watch for wading birds scattered about in the grass. Great egrets, snowy egrets, cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis), white ibis, wood storks, and great blue herons are likely to be anywhere, but they may only be visible for an instant if you drive by too quickly.

About 1.5 miles from the main entrance, begin looking to the left. You'll see a stand of royal palm trees extending their lofty clump of fronds high above a large hardwood hammock. The trees stand as sentinels over Royal Palm Hammock. Once called Paradise Key, this area was the first part of the park to be protected.

Although Hurricane Andrew downed many of the great hardwoods in the hammocks, most of the royal palms bent with the winds, then reclaimed their lofty positions after the storm passed.

The turn to Royal Palm Hammock, which features the trailhead for the Anhinga and Gumbo Limbo trails, is 2 miles from the main entrance. As you enter the hammock, look in the woods on the left where you can still see the remains of gumbo-limbo and bay trees toppled by Hurricane Andrew. Notice that many of the smaller trees that survived the storm had many of their branches stripped away.

The small visitor center at Royal Palm includes a bookstore and a small museum in which original artworks by wildlife artist Charles Harper depict life in a freshwater slough. With three-dimensional, overlapping layers of sharp-edged wildlife cutouts, the artist has reduced the surrounding environment to basic outlines and angles. His stylized murals seem to strip away all but the stark reality of the web of life—alligators eating possums, birds eating snails, snakes eating frogs, fish eating smaller fish, alligators eating lizards and fish, frogs eating lizards, Anhingas eating everything but alligators.

[Fig. 12(2)] With its always-fulfilled promise of wildlife encounters, the Anhinga Trail is one of the most famous trails in America. It offers a close-up view of Taylor Slough, a miniature, but complete version of the larger Shark River Slough that anchors the river of grass to the west.

The best wildlife viewing along this 0.5-mile paved trail and boardwalk takes place during the winter dry season when the area's wildlife comes to the remaining water in the slough. Fish concentrated in the clear waters become easy prey for the birds and alligators that gather.

The trail begins next to the borrow pond behind the small visitor center. Look in the water for alligators and one of their favorite foods, the log-shaped Florida gar (Lepisosteus platyrhincus), which is easy to distinguish in the clear water by its long body and long snout. This light brown, spotted fish is seldom eaten today but was popular fare for Indians.

From the pond the trail follows part of the roadbed of the old Ingraham Highway, which was constructed in 1916 in an early attempt to develop part of the region. The road also provided a way for early visitors to discover the natural values of the Everglades, which in turn led to the protection of this area. The Florida Federation of Women's Clubs preserved and dedicated the area as Royal Palm State Park in 1916.

The shallow borrow canal next to the trail was dug when the highway was originally constructed. Birds and fish have found it to be as useful as any pond.

Florida softshell turtles are commonly spotted in the clear water. The large turtle spends most of its time underwater, even hiding its entire body in the mud to wait for prey, and occasionally using its long neck to raise its tubular snout to the surface for a breath of air.

Look in the water beneath the first little bridge you come to for huge largemouth bass lying almost motionless in the slow current. Look in the reeds near the bridge for a resident great blue heron and a green-backed heron. In the sawgrass beyond the canal look for great egrets, snowy egrets, great blue herons, and great white herons.

Although it is considered a color variation of the great blue heron, the great white is the largest of all the herons. Great white herons are frequently seen in the Anhinga Trail area and around Florida Bay. They stalk a great variety of large prey, including rodents and other birds. Both great white and great blue herons feed by standing nearly motionless waiting for their prey to come within the strike radius of their lightning-fast neck and beak.

Turning left onto the boardwalk, the trail next takes you out over a mature sawgrass prairie. Notice how tall the sawgrass is here, reaching heights of 8 feet or more. The triple-edged sawgrass is actually an ancient sedge and is the most abundant land plant in the Everglades.

Passing on through a thicket of willow trees (Salix caroliniana), the boardwalk extends out over the open, pondlike heart of Taylor Slough where visitors encounter what can only be described as a living mural of wildlife. Anhingas (Anhinga Anhinga) and double-crested cormorants adorn the clumps of pond apple (Annona goabra) and willow trees surrounding the slough.

When hungry, both Anhingas and cormorants dive into the clear water in pursuit of sunfish species such as bluegills and shellcrackers. Often putting on a show for the visitors gathered along the boardwalk, they swim around until sighting their prey, then move in for the kill.

The purple gallinule, one of the most strikingly beautiful birds in the Everglades, can often be seen walking gingerly on spatterdock (Nuphar luteum) leaves using its very long toes to lift the leaves in search of insects. Nearby, common moorhens (Gallinula chloropus) (also known as Florida gallinules) and coots can usually be seen floating on the water's surface, reaching down for an occasional mouthful of underwater salad.

Alligators, along with an occasional Florida brown water snake (Storeria dekayi victa) or Florida cottonmouth, will drag themselves onto the muddy bank below the boardwalk to absorb warmth from the afternoon sun. If you see a big green frog, it's probably a pig frog (Rana sphenocephala). This is the largest frog in South Florida and the most common frog in the Everglades.

A number of exotic species that have escaped from the Florida aquarium trade can also be spotted in Taylor Sough. They include blue tilapia (Tilapia aurea), Mayan cichlid (Cichlasoma urophtalmus), oscar (Astronotus ocellatus), and the unusual walking catfish, which actually uses its fins to walk from pond to pond.

All of these species rely on a food web that begins with a sun-nurtured, heavy growth of algae, which feeds and shelters tiny insects and animals. These in turn are eaten by mosquito fish, sailfin mollies (Mollienisia latipinna), and other small fish that also feed upon the plentiful mosquito larvae. These small fish are eaten by everything from sunfish to wading birds.

Pond apple trees (Annona glabra), also known as alligator apple or custard apple, grow in the shallower areas of the slough. When ripe, the yellow fruit is edible but has the taste of turpentine. Turtles and alligators feed on the fruit when it falls. Great thickets of these water-loving trees once grew in a wide band along the southern end of Lake Okeechobee. The trees were removed long ago to make way for farming.

Many of the trees around the slough are decorated with an array of air plants. Resembling pineapple tops, these bromeliads aren't parasites, but merely use the tree as support. They get their nourishment from the rain and debris that falls into little pockets at the base of the plant. Frogs, snakes, and insects add their droppings to the nutrient pool. Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides) and tree orchids are air plants found in the park.

[Fig. 12(2)] This paved, 0.3-mile loop trail passes through the junglelike vegetation of Royal Palm Hammock. Royal palms, gumbo-limbo trees, wild coffee, strangler figs (Ficus aurea), and lush aerial gardens of ferns and orchids grow in this dense lush hammock, an island only 1 foot higher than the surrounding land.

Before Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the forest floor was dark and shaded by a

thick tree canopy. After the storm toppled many of the mature trees, sunlight

found the ground and the understory began to grow rapidly. Within 10 days of

the storm, the leaves began to sprout. And as is the way in the tropics, plants

began growing on plants in their search for sunlight. It was a scene that was

repeated in hammocks throughout the Everglades.

The hammock today is healthy and growing, and it is alive with insects, reptiles, birds, and small mammals. But the dense vegetation makes all but the biting insects difficult to find. One species that is quite visible because of its bold yellow stripes is the zebra butterfly. A tropical species from the West Indies, small groups of this butterfly can often be seen wandering slowly along the trail visiting with the vegetation. It is a prolific species in part because during its caterpillar stage it feeds on passion flowers, which give it a bitter taste, discouraging predators.

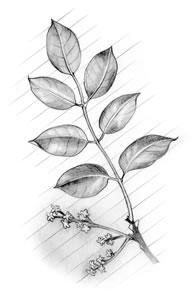

By growing close together in a hammock, plants help each other retain moisture and resist fire and frost. There is also a pronounced similarity of leaf shapes among the various trees in hammocks. Almost all the leaves are elliptical with smooth margins and waxy surfaces. A pointed "drip tip" allows excessive rain and dew to quickly drip off the leaf, and the waxy surface slows evaporation during the dry season.

At one point the paved trail crosses a wide grassy track leading into the hammock. This is a 0.8-mile section of the old Ingraham Highway that leads to the Hidden Lake Research Center.

Leave the Gumbo Limbo Trail and follow the old highway for a short distance. After a couple of hundred yards you'll enter a grove of royal palms, at more than 100 feet tall, standing high above the rest of the vegetation. A little farther and you'll see plants that look familiar.

Common house plants such as variegated philodendrum and elephant ear philodendrum (Monstera deliciosa) can be seen growing up and over the other plants along both sides of the trail and winding up the trunks of some of the royal palms. A few yards farther and you'll find a grove of wild orange trees that are mixed in with the hammock vegetation.

Somewhere off the trail a short distance to the north, through almost impassable foliage, is the site where the Royal Palm Lodge once stood and where early visitors could enjoy the tropical environment. The unusual plants were part of the original landscaping. The lodge, which was completed in 1919, was moved to Homestead in 1954.

[Fig. 12] A portion of the old Lake Ingraham Highway that once connected Miami with Cape Sable has been opened as a hiking trail. The trail follows the old limestone roadbed for 11 miles.

To find the beginning of the trailhead, go back toward the main road from the Royal Palm parking lot and turn left (southwest) down the paved road leading to the Daniel Beard Research Center. Continue straight at the point where the road takes a hard curve to the right. Watch out for potholes in the unimproved road. When you pass the gate to the Hidden Lake Research Center you'll actually be driving on the Old Ingraham Highway.

The road ends at Gate 15, which bars vehicle traffic but allows hikers and off-road bicyclists to continue. There are two campsites on the trail: the Ernest F. Coe Campsite is 4 miles out, and the Old Ingraham Campsite is 10 miles down the roadbed. Backcountry camping permits are required and the road can be flooded during the wet season.

The trail crosses the sawgrass prairie, and because it parallels the Homestead Canal it provides wildlife viewing opportunities similar to those found in Taylor Slough.

Even if you don't plan a hike, a drive down the old road is a chance to experience a little history. This somewhat circular area is known as the "Hole-in-the-Doughnut" because it's surrounded by undeveloped wetlands. Most of the area had been turned into crop and pasture land before the park was created. Brazilian pepper, which lines much of the road open to automobiles, is an unwelcomed exotic plant that has taken advantage of the disturbed lands. Scientists at the Daniel Beard Research Center are working to find ways to restore native vegetation.

Before leaving, drive down the road to the research center and to the restoration plots beyond. The road passes through a very nice pine and palmetto forest. Watch the wires along the road for hawks and other birds. During the late evening you have a chance of seeing a white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) or a gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus).

[Fig. 10] Back on the main road and headed toward Flamingo again, you'll notice an occasional panther crossing sign. With very few of these big cats remaining in the area, and their penchant for travelling mostly at dusk and after dark, the chances of seeing one are very slim.

Two miles below the Royal Palm Road on the main road is the turn to Long Pine Key, a popular center for camping, hiking, and bicycling. The key is a continuation of the Atlantic Coastal Ridge that runs along the southeastern Florida coast.

Hiking trails of 3, 5, and 8 miles are interconnected to form more than 28 miles of trails through the pine forest. The longest loop trail follows an old auto trail that is now restricted to hiking or biking. Pick up a map of the trails at the visitor center before starting out.

The pine forest on Long Pine Key is the most diverse in the park, with between 100 and 200 species of plants recorded. About 20 are found here and nowhere else, and among them are milk pea (Galactia pinetorum) and narrow-leaved poinsettia (Poinsettia pinetorum).

While hiking look for species such as rough velvetseed (Guettarda scabra), willow bustic (Dipholis salicifolia), tetrazygia (Tetrazygia bicolor), and satinleaf trees (Chrysophyllum oliviforme). Leaves of the satinleaf are dark green on top and shiny bronze underneath, and they appear to shine and shimmer when the wind blows.

The Long Pine Key picnic grounds are comfortable and bug-bearable in the cooler months. Picnic sites with tables are scattered throughout the pine forest and connected by narrow paths. A nearby lake always seems to hold an alligator or two. During hot weather the tall pine trees offer very little shade.

Flocks of red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) are common in the picnic area, as are the smaller pine warbler (Dendroica pinus), and red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus,) which actually has red on its head, not its belly. Just before dark look for three different species of owls, Eastern screech owls (Otus asio), barn owls (Tyto alba), and barred owls (Strix varia), on tree branches or actively hunting in the campgrounds and picnic grounds.

The Long Pine Key Campground has 103 tent and RV sites and pull-through sites for vehicles up to 35 feet. Each site has a picnic table and grill. There are restrooms, and water is available, but there are no hook-ups. The sites are well spaced, which is nice because the vegetation in the pine woods between sites isn't very tall.

[Fig. 12(3)] A short, paved, and interpreted trail winds through another portion of pine forest about 2 miles down the main road at the Pinelands Trail pull-off. The 0.5-mile paved trail is wheelchair accessible.

On the way to the Pineland Trail notice how the landscape alternates from pine forest to sawgrass prairie and back again. These sections of forest are called keys (a South Florida name for islands) because they are surrounded by sawgrass prairie wetlands.

Hurricane Andrew left many pines in this area snapped off. Many of the largest trees were blown completely over. Many trees, however, survived because of their ability to bend. The dominant plant in these lands, the South Florida slash pine, is a native species adapted to a hurricane-prone climate.

Unfortunately, the 20,000 acres of the pineland community in the park represents nearly all that remains in North America of this unique habitat, making it one of the continent's most endangered pine communities.

The pine forest is also a fire forest, which means the habitat has evolved to depend upon periodic wildfire. When fire, often caused by lightning, sweeps though the area, hardwoods that try to invade the pinelands are destroyed while the pine trees' thick bark insulates them from all but the hottest fires. If hardwoods are able to grow, they will eventually shade the forest floor, which prevents young pine seedlings from germinating.

Various other plants have developed alternative fire-resistant mechanisms. The fernlike coontie, which has large underground stems, can burn to ground level, then quickly sprout again. Another common pinelands plant, saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) wrap its buds in layers of protective tissues.

Today, controlled burns are performed by the Park Service in an attempt to duplicate the role of natural fires. On the Pinelands Trail, at the base of some of the trees, you can see charring from earlier fires. Whenever possible, wildfires caused by lightning storms are allowed to follow their natural course and burn out on their own.

Watch out for poisonwood (Metropium toxiferum) along the Pinelands Trail. A close relative of poison ivy, the poisonwood tree can cause a severe rash. The tree has drooping compound leaves with five to seven leaflets. The shiny leaves and reddish-brown bark often have dark splotches on them. Animals can eat the berries with no ill effects.

Continuing south along the main road from the turnoff for the Pinelands Trail, the pine forest begins to die out and the road again passes across the edge of the river of grass. The sawgrass extends from horizon to horizon like an Oklahoma wheat field, broken only by the occasional domedshaped silhouette of a hardwood hammock or cypress head.

Red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) and American kestrels are commonly seen in the short cypress trees and small hammocks near the road. Wood storks, great egrets, white ibis, and snowy egrets can be seen in wet areas along the road.

In the summer, puffy white clouds with flat anvil bottoms form almost every afternoon over the Everglades. The clouds soon grow into thunderheads reaching great heights. When the rain begins and the thunder starts rumbling across the sawgrass, they almost seem to lean forward as they sweep across the landscape trailing a dark downpour behind. Because of the flat landscape, you can see these great storms from many miles away, and appreciate how fast they move if they are heading your way.

Don't stay to watch for too long, however. Florida is known as the nation's thunderstorm capitol and leads the nation in deaths from lightning. Researchers have also pointed out that Florida lightning is particularly powerful because the tall storm clouds that it comes from are more highly charged than the average thunderhead.

Although the rainstorms can be intense, they seldom last more than two hours, and often pass by in only a few minutes. The sauna-like conditions that persist for hours after these storms pass give true meaning to the statement, "It's not the heat it's the humidity."

If there's not too much traffic, consider pulling over to the side somewhere along the main road. Step out of your car and appreciate the quiet of the Everglades. If you stand with your back to the road and look out across the sawgrass, you can feel the Everglades the way you might feel a great desert or mountain range. See the wind blow across the grass, listen to the sounds of birds and insects. Feel the life of a place that may have seemed lifeless through a car window.

Step closer, look at an individual strand of sawgrass. Notice how it has three edges, each with an impressive row of serrated teeth. Look up again and imagine what it must have been like for the first explorers, or the Native Americans who turned to this harsh land for refuge from an unjust government.

At one point the road passes through a dwarf cypress forest. The miniature cypress trees, although as old as their taller cousins, are merely stunted because they grow where there is only a thin layer of top soil and a short supply of nutrients.

[Fig. 11, Fig. 12] Thirteen miles south of the main entrance, Pay-hay-okee, which is the Seminole word for "grassy waters," is an overlook worth looking over. A short road takes you to the edge of the Shark River Slough where the park has built a tower, which provides a exceptional view of the river of grass.

A very short boardwalk (0.2 mile) leading out to an observation tower passes close to a small stand of pond apple trees. This is an area where visitors are likely to see red-shouldered hawks (Buteo lineatus) in the treetops and wood storks feeding in the shallow water around the bases of the cypress trees. Bald eagles are also often sighted in the area.

Look at the base of the tall sawgrass next to the boardwalk. That thick mat of brown ooze floating on the shallow water is periphyton, which is made up of several different types of algae and is one of the most important components of the sawgrass prairie. Serving as the base of the food web, periphyton hosts a variety of tiny insects and crustaceans and makes up much of the soil in which the sawgrass grows. During drought the thick mats help to seal moisture in the ground.

This overlook provides one of the best views of the sawgrass. Even from the vantage point of the tower, the yellow and green sawgrass extends to the horizon in a uniform sheet broken only by the occasional cypress dome. The water in this river began its journey hundreds of miles to the north and may have taken nearly a year to get this far. The Pay-hay-okee Overlook is also one of the best spots in the park to watch the sunset over the sawgrass. In fact, someone even put a bench in just the right location for watching the sun fall into the sawgrass.

As darkness slides over the land, many of the animals seem to come alive with a desire to communicate. Croaking, squawking, chattering, squealing, chirping, and buzzing sounds fill the air.

At the same time, the dark blue evening sky fades into a bright orange band that runs along the horizon and reflects through the thin cypress in the water below. Slowly, faint green and yellow bands appear above the deep orange, forming a horizontal rainbow that lasts for only the final few minutes of nature's daily show.

[Fig. 12] Seven miles farther down the road to Flamingo, and 20 miles from the main entrance, Mahogany Hammock provides a revealing look into a unique Everglades habitat. A circular, elevated 0.5 mile boardwalk has been constructed and passes through the heart of a mature hardwood hammock dominated by huge mahogany trees.

Even the short road out to the hammock offers an excellent scenic view of

a sawgrass prairie dotted with swamp lilies and stunted cypress trees. Look

for red-shouldered hawks and kestrels in the short, skimpy trees. The hammock

is also a good place to see barred owls (Strix varia). Look for their

dark shapes in the upper branches.

Just to the right of the point where the boardwalk enters the hammock is a large clump of rare paurotis palms (Aeoelorr haphe wrightii). These skinny palms can also be found in urban developments around Miami where they have been used extensively for landscaping.

Inside the hammock, a couple hundred feet down the right-hand fork, is a plaque that reads, "The oldest living [West Indies] mahogany tree in the United States." The tree is an astounding sight. According to the National Registry of Big Trees, it has a girth of 128 feet and a height of 51 feet. The old giant has branches bigger than the trunks of the other mature mahogany trees in the hammock. Like a great grandfather watching over his brood, it towers far above the other trees.

Since this tree was nominated for champion status in the 1975, however, a couple of larger trees have been discovered, including a Key West tree that has a girth of 175 feet and a height of 79 feet.

Prior to 1960 this isolated hammock was largely composed of giant mahogany trees and a very few plants that could grow beneath the dark canopy. That was before the 180 mph winds of Hurricane Donna toppled many of the largest trees, allowing sunlight to penetrate to the forest floor.

Almost immediately, new species began competing for the sunlight. Today the hammock features a thick growth of tropical plants, cabbage palms, royal palms, strangler figs, and gumbo-limbo trees.

At one point along the walk, giant leather ferns (Acrostichum danaeifolium) growing up and around the boardwalk add to the primeval feeling of the junglelike environment. Also look high in the trees for resurrection fern (Polypodium polypodioides), a plant known for turning brown and drying up as if dead, only to revive within minutes of the first rain. Tree orchids found in the hammock include cowhorn orchid (Cyrtopodium punctatum), butterfly orchid (Encyclia tampensis), clam shell orchid (Encyclia cochleata), twisted air plant (Tillandsia flexuosa), and needle leaf air plant (Tillandsia setacea).

The rest of the road to Flamingo features a number of spots worth a two-hour picnic, or a 10-minute stop over, depending upon your mood and schedule. Each stop has the potential to present a special surprise, another discovery.

A few miles below Mahogany Hammock, near the turnoff to Paurotis Pond, mangroves begin to dominate the roadside vegetation. Mostly red mangroves, the trees on the west side of the road grow in a borrow canal created when the road was built. In the summer watch the sky just above the trees for the tilting and dipping flight of a swallow-tailed kite (Elanoides forficatus). The startling black and white birds have long forked tails that make them easy to identify.

Any time of the year, the canal behind the mangroves offers some terrific birding opportunities. Wading birds of all types—great blue herons, wood storks, white ibis, roseate spoonbills, great egrets and snowy egrets, tricolored herons—gather in large numbers in open spots in the old canal. As you drive by, watch for gaps in the trees where you can see back into open water. If you spot an accumulation of birds, you can carefully pull off and walk back for a closer look.

Paurotis Pond is a picnic area overlooking a small borrow pond. It's a fair place to spot wood storks and some wading birds.

A few picnic tables and a scenic view of a freshwater pond highlight the pull-off at Nine Mile Pond. Actually a series of connected spots, this is the starting point for the Nine Mile Pond canoe trail. Look for alligators and the regular assortment of wading birds. It's also a good place to see bald eagles, osprey, and wintering waterfowl. In summer look for small flocks of white-crowned pigeon and swallow-tailed kites.

West Lake is another stop that offers some excellent birding opportunities. In winter, depending upon the severity of the weather, look for migrating waterfowl in the lake behind the boat launch. Northern shoveler (Anas clypeata), blue-winged teal (Anas discors), green-winged teal (Anas crecca), American widgeon (Anas americana), ring-necked duck (Aythya collaris), and lesser scaup (Aythya affinis) have been sighted there. The boardwalk through the mangroves and out to the main lake often reveals rafts of American coots, and some wading birds along the shore.

Wildlife calendars all over the country contain photos of birds taken at Mrazek Pond, the next stop on the road. It's a Jekyll and Hyde kind of spot. When the water is high the wildlife is scarce, but when the water is low it earns its reputation as the most highly photographed spot in the park.

On most days in the winter, there's a constant crowd of photographers and bird watchers posted at the water's edge. Binoculars, spotting scopes, and telephoto lenses steadily record the changing picture of the pond's wildlife.

One day may find hundreds of great egrets stationed in the trees and shallow water. Another day might find rafts of white pelicans performing their feeding ballet. Working shoulder to shoulder as a group they drive schools of minnows up against the shore. Then at some unknown signal, all the birds dip their large pouches at once, then raise them high to let the water run out before gobbling down the filtered contents.

On any visit to the pond, you might also see roseate spoonbills, common moorhen (also known as a Florida gallinules), American bitterns (Botaurus lentiginosus), least bitterns (Ixobrychus exilis), Anhingas, double-crested cormorants, great blue herons, white ibis, pied-billed grebes, little blue herons (Florida caerulea), and tricolored herons.

Another mile down the road, Coot Bay Pond, which is surrounded by a thick growth of red mangroves, is a nice place for a picnic, but seldom contains much in the way of visible wildlife. The pond is connected by a small waterway to the much larger Coot Bay.

For a brief time before the area became a park, a fishing lodge sat at this spot next to Coot Bay Pond. American coots, which were once plentiful on Coot Bay, have a gizzard much like a chicken. Apparently the rest of the bird wasn't much to brag on, but the lodge was known for a special dish of coot gizzards and rice.

Along the final few miles to Flamingo the road passes between high walls of red mangroves and Brazilian pepper. Again watch for openings in the almost solid walls of vegetation where wading birds will be gathered.