[Fig. 49, Fig. 50, Fig. 51, Fig. 52] The Sierra National Forest can mean many different things to many visitors. For those who come here from Los Angeles or the San Francisco Bay area each year, the forest means camping or renting a cabin at Huntington Lake and sailing every day. For fishing enthusiasts, it means fishing in a backcountry reservoir such as Lake Thomas Edison or Florence Lake. And, for backpackers, the Sierra forest means hiking near the crest at 13,986-foot Mount Humphreys. Four million people visit this forest every year.

From a practical standpoint, the Sierra forest represents a marriage of commercial interests—hydroelectric companies, cattle grazers, and others—and nature. Hydro companies have left the most noticeable imprint on the mountain ecosystems here.

There are 29 powerhouses on the San Joaquin River watershed, and Southern California Edison's chain of hydro lakes includes 11 major reservoirs. The reservoirs' combined storage is more than 500,000 acre-feet of water—roughly enough water to supply a California city of about 2 million people for an entire year. Two massive reservoirs, Courtright and Wishon, are part of the Pacific Gas & Electric Company hydroelectric network on the Kings River. In one place in the Sierra forest, Pacific Gas & Electric blasted a cavern several thousand feet deep inside a granite mountain to bury a massive powerhouse.

Yet, a few dozen miles away from the hydro projects, the Ritter Range within the Sierra Nevada displays small glaciers, jagged 12,000-foot peaks, and deep canyons. It is as primitive as any part of the Sierra crest. And, all through the high country, there are more than 350 natural lakes left by the receding glaciers more than 10,000 years ago.

Forest managers have been given a tool for keeping this forest wild—wildernesses. The eastern side of the Sierra forest is lined with wildernesses, including the Ansel Adams, John Muir, Dinkey Lakes, Kaiser, and Monarch wildernesses. The best Monarch Wilderness access is in Sequoia National Forest, so the Monarch will be detailed in the Sequoia forest section of this chapter (see page 295).

Together, the Sierra forest wildernesses provide a kind of natural corridor between Yosemite National Park on the north and Kings Canyon National Park on the south. Only the Kaiser Wilderness, just north of Huntington Lake, is an island away from the contiguous string of wildernesses.

The Sierra forest began in 1893 under the name of Sierra Forest Reserve, encompassing more than 4 million acres and most of the Southern Sierra. Over the next several decades, it shrank as other forests and national parks were established. But the Sierra forest has always contained the high Sierra and a connection to the Eastern Sierra.

There

is no way to get from the western slope to the Eastern Sierra by passenger

car. This area is part of the longest block of wild lands in the Sierra

where no paved pass exists to cross the mountain range. Visitors interested

in crossing the range have to drive north to Yosemite and cross on Tioga

Pass, or drive more than 100 miles south to Highway 178 in Kern County.

There

is no way to get from the western slope to the Eastern Sierra by passenger

car. This area is part of the longest block of wild lands in the Sierra

where no paved pass exists to cross the mountain range. Visitors interested

in crossing the range have to drive north to Yosemite and cross on Tioga

Pass, or drive more than 100 miles south to Highway 178 in Kern County.

In 1879, there was earnest discussion of building a road from Fresno to Mono County through the present-day Sierra forest, but the attempt was doomed because Mammoth Mining Company closed the next year. With no financial support, the idea fizzled. Other proposals have been entertained over the last century, but none has panned out.

Now Beashore Road to Clover Meadow in the northern Sierra National Forest is as far as developed roads go. The road and its access roads stop about 18 miles short of crossing the crest and reaching Mammoth Lakes. The only way to cross the Sierra in this area is to walk, ride a stock animal, or fly by plane—although there is no commercial landing strip in the forest. And a lot of people want this part of the mountain range to remain a haven for plants, animals, and recreation rather than cars.

Unlike the steep escarpment of the Eastern Sierra, the western slope rises gradually over a long distance—40 miles or so in the Sierra forest. So foothills are a big part of the ecosystem. A large variety of animals reside in the foothills year-round because of the milder climate. The animals include Gilbert's skink (Eumeces gilberti), the screech owl (Otus asio), Bewick's wren (Thyromanes bewickii), and spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis).

Several kinds of woodland oaks provide habitat for many kinds of animals. The oaks range from the San Joaquin Valley floor to 6,000 feet in the Sierra. Species include the valley oak (Quercus lobata), black oak (Quercus kelloggii), blue oak (Quercus douglasii), and Oregon oak (Quercus garryanai).

The foothill woodlands also are known for adjacent grasslands. Nineteenth century California had millions of grassland acres that have since become farmland. But some grasslands still exist, and they are easy to see from the roads as visitors drive into the forest. In spring, look for wildflower displays that include baby blue-eyes (Nemophila menziesii), long-spurred plectritis (Plectritis ciliosa), evening snow (Linanthus dichotomus), and American vetch (Vicia americana).

Native Americans, the Western Paiutes, lived in the grasslands and foothill areas of the Sierra forest hundreds of years before other humans arrived. Other tribes also came into the Sierra on a seasonal basis. The Mono tribe came from the Eastern Sierra to Mono Hot Springs, just south of Lake Thomas Edison, to participate in spiritual cleansing rites during the summer. Some tribes left behind holes in the granite bedrock near the San Joaquin River where they ground acorns for food. There is also evidence of Native Americans around the Kings River.

Today, the Kings River, on the forest's extreme southern boundary, is considered a fine whitewater rafting stream. When the snow melts in spring and summer, about 1.7 million acre-feet of water roll down the river over several months. That amount of water varies wildly because California's capricious weather can spin off five or six consecutive drought years, followed by three or four near-record rainfall years.

[Fig. 49(2)] The Sierra Vista National Scenic Byway is the best way to see the Sierra National Forest from your car. Indeed, it may be the quickest and easiest way to see a huge cross-section of life in the Sierra Nevada. It runs from the foothills at about 2,800 feet in elevation around North Fork to more than 7,000 feet at Globe Rock, Cold Springs Summit, and Fresno Dome.

Make sure your gas tank is full and your tires are properly inflated. This route is about 100 miles, and 20 of them are not paved. In other words, this trip will probably take most of the day. Allow at least four or five hours.

Visitors can fill up with gas and find food in the small community of North Fork. They can also visit the Mono Indian Cultural Museum. The scenic byway begins about 3 miles south of North Fork at Minarets Road, which can be reached from Road 223 in North Fork. Before they start the drive, visitors may want to take a 6-mile detour down Italian Bar Road to see the geographic center of California. The much-debated subject of the state's geographic center was settled with Global Information System instruments several years ago. The area is marked along Italian Bar Road. Return to Road 223 and continue driving southeast until you reach Minarets Road.

Along the Sierra Vista National Scenic Byway, Redinger Overlook at 3,700 feet provides a good view of the foothills and vegetation. Redinger Lake, which can be seen from the overlook, is part of the hydroelectric system built by Southern California Edison Company. In the chaparral plant communities of this area, common shrubs are birchleaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus betuloides), coyote bush (Baccaris piluaris), and California coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica).

About 6 miles farther along, as the road slowly begins to wind north, there is Ross Cabin at 4,000 feet in elevation. Jessie Blakey Ross built the cabin in the 1860s. Jessie had moved west with his parents for the Gold Rush. His log cabin is among the oldest still standing in this area.

The next stop is Mile High Vista at 5,300 feet. The Kaiser Wilderness and Mammoth Pool Reservoir, another hydroelectric lake belonging to Southern California Edison Company, stretch before visitors. The U.S. Forest Service closes the Mammoth Pool area between May 1 and June 15 to allow migrating deer to pass through safely. Apparently, before the pool was constructed, the area was a meadow along a corridor where mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) migrated annually from the foothills to the higher elevations. The deer apparently have not changed their route over the last century. Campgrounds in the Mammoth Pool area include Placer and Sweetwater.

Arch Rock at 6,200 feet is the next stop, about 14 miles from Mile High Vista. It can be seen from a marked turnout, but visitors may want to take the short hike to see how erosion formed the granite into an arch. About 5 miles beyond Arch Rock is the Clover Meadow Forest Service Station and the Granite Creek Campground. Turn right on the marked access road and drive 2 miles. The Ansel Adams Wilderness is a few miles beyond the campground next to the access road.

Minarets Road becomes Beashore Road at the Clover Meadow turnoff. The pavement ends here, and it will not begin again for about 20 miles. The Minarets Pack Station is about a 0.5-mile hike south of Beashore Road. About 11 miles down Beashore Road, visitors will see Globe Rock at 7,152 feet. It features a large granite rock perched and balanced on a smaller rock, a phenomenon caused by freezing and erosion at the base of the formation. Campgrounds along Beashore include Chilkoot, Graggs Camp, and Upper Chiquito.

Lodgepole pine (Pinus murrayana) and red fir (Abies magnifica) are common in the forest here. The vegetation below the trees must be able to grow without a lot of sun. Look for the alpine prickly currant (Ribes montigenum), tobacco bush (Ceanothus velutinus), and Labrador tea (Ledum glandulosum).

About 8 miles beyond Globe Rock, visitors have the choice of turning right from Beashore onto Sky Ranch Road or continuing straight on Beashore to Bass Lake. Either way, visitors will wind up on Highway 41 where the byway concludes just north of Oakhurst. Along Sky Ranch, visitors can see the giant sequoia. Bass Lake, known as a fine fishing hole, is another picturesque mountain lake formed by a Pacific Gas and Electric Company hydroelectric project.

[Fig. 49(1)] Nelder Grove has more than 100 giant sequoias in its 1,500 acres, and the Shadow of the Giants Trail offers visitors an up-close look at many of them. At the end of the trail is the Bull Buck Tree, once considered the largest sequoia in the country. The General Sherman Tree in Sequoia National Park holds that distinction now.

Along the trail, visitors may notice incense cedar (Libocedrus decurrens) and white fir (Abies concolor) in the grove. Some of the incense cedars appear to have cavities running parallel to the grain of the bark. These are the work of a dry-rot fungus (Polyporus amarus).

Another interesting part of Nelder Grove is the Graveyard of the Giants, not far from the Shadow of the Giants Trail. Visitors will find nearby Nelder Grove Campground, which has no piped water. However, there is no fee to stay in this campground.

The Ansel Adams [Fig. 40, Fig. 41, Fig. 42] and John Muir [Fig. 42, Fig. 43, Fig. 44, Fig. 46] wildernesses straddle the crest of the Sierra Nevada, falling into both the Sierra and Inyo national forests. Together, the wildernesses spread over 800,000 acres of the high Sierra. Many of their most famous features—such as part of Mount Whitney, the Devils Postpile National Monument (see page 226), and Thousand Island Lake—are reached from the Eastern Sierra. For a fuller description of each wilderness, see the Ansel Adams Wildernes, (page 205) and the John Muir Wilderness (page 233) in the chapter on the Eastern Sierra. In the Southern Sierra, the Sierra National Forest has its share of wilderness features, too. Fishing, camping, horseback riding, backpacking, and hiking are the main activities.

Though there are dozens of picturesque glacial lakes carved into the granite on the western side of these two wildernesses, the four lakes known best in these parts are hydroelectric lakes. They are Lake Thomas A. Edison, Florence Lake, Courtright Reservoir, and Wishon Reservoir. All are massive compared to the natural lakes in this area.

Edison and Florence, part of Southern California Edison Company's hydroelectric chain of lakes, help harness the 1.7-million-acre-foot runoff each year coming down the granite canyons of the San Joaquin River watershed. Courtright and Wishon are in the Kings River watershed to the south, and they are part of the Pacific Gas and Electric Company hydroelectric complex. None of the four lakes is technically inside a wilderness, but the wilderness surrounds Edison and Florence. And wilderness borders Courtright and Wishon. Campgrounds and other attractions can be found near the lakes. About 3 miles from Edison, visitors will find Mono Hot Springs, which provides people a chance to experience an exhilarating dip in mineral waters.

Fishing enthusiasts like the lakes because they can find plenty of rainbow trout, brown trout, and Eastern brook trout. Hikers and backpackers enjoy the high Sierra vistas, dominated by granite that began forming 80 million to 100 million years ago.

The backcountry trails in these wildernesses are heavily used, and they traverse some of the most rugged country anywhere in this mountain range. Like the trails in the Central Sierra, these trails require physical fitness because they are many miles from civilization.

In the 6,000- to 8,000-foot forest belt dominated by lodgepole pine, ponderosa pine, and red fir, the California spotted owl (Strix occidentalis) can be found within 0.25 mile of streams. The owl prefers living in mixed conifer parts of the forest dominated by red fir and white fir where old-growth trees of more than 30 inches in diameter can be found. The owl is considered a "Forest Service sensitive species," meaning its numbers have dwindled and its habitat is disappearing.

The rare plants in this part of the forest include golden annual lupine (Lupinus citrinus) and unexpected larkspur (Delphinium inopinum). The lupine is endemic to the Sierra forest. Other endemics found here are the two-lobed clarkia (Clarkia biloba ssp. australis), Kings River buckwheat (Eriogonum nudum var. regirivum), many-flowered lily (Erythronium pluriforum), and Rawson's flaming trumpet (Collomia rawsonia).

[Fig. 51(1)] People hiking the Maxson Trail to Post Corral Meadows consider this trek to be a light weekend of walking. They camp around the meadows and return the next day. So, if you're interested in a short backpack into the John Muir Wilderness, this is a good sampler filled with views of the high Sierra. You will need a wilderness permit for an overnight stay. For the wilderness permit, write the forest at 1600 Tollhouse Road, Clovis, CA 93611-0532, or stop on your way to the wilderness.

There is one area of interest around Courtright Reservoir where the trail begins. It is called the Courtright Intrusion Zone Geologic Contact Area. Geologists say visitors can see the edge of two massive plutons meeting at this place, which is just east of the parking area. The edge of metamorphic rock, once part of an ancient seabed about 180 million years ago, is visible as reddish hornfels along the intrusion zone of the two plutons. Another interesting geologic feature is the outline of an old, inactive fault between the two plutons.

[Fig. 51(2)] It's hard work, but most people appreciate the views after climbing several hundred feet of granite at the start of this trail. Wishon Reservoir stretches below. To the southeast, visitors will see Mount Hoffman at 9,622 feet. The glacial advances over the last 1.5 million years buried this area under ice several times. The last of the retreating glaciers, about 11,000 years ago, finished the job of carving the spectacular spires and domes visible to the north.

Some people like to walk up the first 2 to 3 miles of Woodchuck just to see the views and turn around. Visitors do not need a wilderness permit for a day hike. In September, the quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) is dazzling as it lights up meadows with yellow leaves. Lost Peak at 8,476 feet is to the north, and Loper Peak at 10,059 feet can be seen in the distance as the trail enters the John Muir Wilderness.

Farther into the John Muir Wilderness, the Woodchuck Trail comes to bridges made from local timber. Soon hikers reach Moore Boys Camp, the end of the line for this hike. For bird watchers, there is plenty to observe in summer. The willow flycatcher (Empidonas tralii), considered a sensitive species in danger of becoming rare, can be seen in this area. Also, look for the poor-will (Phalaenoptilus nuttalli) and mountain quail (Oreortyx pictus).

Kaiser

Wilderness/Huntington Lake

Kaiser

Wilderness/Huntington Lake [Fig. 50] The 22,700-acre Kaiser Wilderness, formed in 1975, gives visitors opportunities to hike, backpack, take photographs, cross-country ski, and fish at elevations between 8,000 and 10,320 feet. But the real attraction of Kaiser is just outside the wilderness boundary—Huntington Lake to the south. Visitors rent summer cabins and spend vacations sailing, hiking, and seeing nature. In winter, downhill skiing enthusiasts flock to nearby Sierra Summit Ski Area. The Kaiser Wilderness gives folks a chance to get away from the development around the lake.

The mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) is probably the easiest large mammal to find in this area, but there are also marten (Martes americana), fisher (Martes pennanti), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), and black bear. Black bears are not considered dangerous, although they occasionally have been known to break into cabins in search of food.

With the development of homes and summer cabins around Huntington, natural fires become more of a concern because there are people and property to protect. A fire in the mid-1990s charred thousands of forest acres near the lake and the community of Big Creek several miles away. Homes and wilderness acreage were threatened, but there was no damage to either.

The human history of the area starts with the Native Americans, particularly the Mono tribe. They hunted and gathered here for centuries, and obsidian used in their tools and weapons has been found in archeological digs in the wilderness.

Huntington Lake, named after utility entrepreneur Henry Huntington, is not natural. Pacific Power and Light Company, now known as Southern California Edison Company, began constructing Huntington dams in 1911, and the lake began holding water in 1913.

Facilities:

Cabins, summer cottages, resorts, gas stations, restaurants, campgrounds,

boat launches, visitor center, and Sierra Summit Ski Area.

Facilities:

Cabins, summer cottages, resorts, gas stations, restaurants, campgrounds,

boat launches, visitor center, and Sierra Summit Ski Area. [Fig. 50(1)] Hikers enter the Kaiser Wilderness after walking 0.25 mile on the trail to Coarsegrass Meadow. The views are filled with red fir, Jeffrey pine, and seasonal wildflowers.

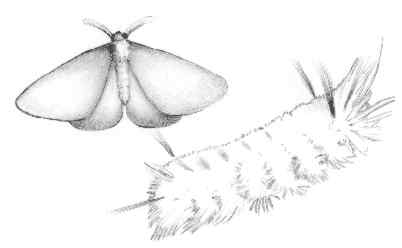

Look for the yarrow (Achillea landulosa) and the meadow fritillary (Fritillary brandegei). On many wet years, the hike passes by pussy paws (Calyptridium umbellatum) and wild strawberry (Fragaria californica).

Twin

Lakes

Twin

Lakes [Fig. 50(2)] Visitors can see some small natural lakes on the Twin Lakes hike. There are quiet fishing holes in the lakes, but they will require a bit of searching to find. Rainbow trout are found in the lakes.

The views from Potter Pass include Banner and Ritter peaks, which are both higher than 12,000 feet. The peaks jut into the skyline at the Sierra crest many miles north of Potter Pass.

[Fig. 50(3)] Hikers like the shaded walk to Rancheria Falls in spring, summer, or fall. It passes along understory vegetation such as buckbrush (Ceanothus cuneatus), white-stemmed gooseberry (Ribes inerme), and chinquapin (Castanopsis chrysophylla).

The falls are about 150 feet high and 50 feet wide. Unlike many falls that dry up by August, the water keeps flowing consistently through the year at Rancheria. The falls continue because the area is in the high Sierra and close to places where a healthy snowpack slowly melts into the streams feeding Rancheria Creek.

Dinkey

Lakes Wilderness

Dinkey

Lakes Wilderness [Fig. 51] The Dinkey Lakes Wilderness is a 30,000-acre area southeast of Huntington Lake and northwest of Courtright Reservoir. Hikers and visitors on pack animals traverse miles of trails for the fishing, views, and camping between the two massive watersheds of the San Joaquin River to the north and the Kings River to the south.

The wilderness is a bit of an oddity because its eastern boundary is an unpaved route, called the Ershim/Dusy Off-Highway Vehicle Route. It forms the boundary between the Dinkey Lakes and John Muir wildernesses and allows off-road vehicles to travel about 31 miles through the heart of wilderness areas. Vehicles can take a back road from Huntington Lake to Courtright Lake.

The highest point, Three Sisters Peak, stands 10, 619 feet just to the south of First Dinkey Lake and southwest of Second Dinkey Lake, which are natural bodies of water. Red Mountain at 9, 874 feet is just outside the northwest shoulder of the wilderness, but it is a striking volcanic feature in an area dominated by granite. Red Mountain was created more than 3 million years ago by an andesite flow. People do climb the peaks, but there are not maintained trails on them.

The trout fishing in the Dinkey Lakes Wilderness is considered excellent. Rainbow trout and Eastern brook trout are caught in the Dinkey Lakes, Swede Lake, and many others. The tough part is getting to the lakes. The closest paved roads are at Courtright and near Huntington. A gravel road will bring visitors within about 0.7 mile of the wilderness. The rest is done on foot. A free wilderness permit is required for overnight visits. To get the permit, write or go to the Sierra National Forest headquarters, 1600 Tollhouse Road, Clovis, CA 93611-0532. Phone (559) 297-0706.

[Fig. 51(3)] The McKinley Grove features about 165 giant sequoia, some of which can be seen from McKinley Grove Road as it passes through the area. Visitors can stroll through much of the 100 acres, which include massive sugar pine and Jeffrey pine, as well as white fir.

The General Washington Tree is the largest of the grove. It is 65 feet in circumference and a small brook actually flows below the root system. Around the trees, visitors will find carpet clover (Trifolium monanthum) and thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus). Also look for the Sierra gooseberry (Ribes roezlii).

The grove remained a bit of an enigma to local residents for decades after it was discovered in the 1860s. The reason: There was little publicity about the grove, and it was not easy to find. Cattle owners grazed their animals near it, and a hydraulic miner worked a claim on Laurel Creek near the grove. But there was no easy way to the grove until 1930. Many historians and environmentalists believe the isolation may have helped the grove survive.

The Kings River has turbulent rapids, huge whirlpools, and smooth open water. It has been attracting boaters for many years. Three companies are known for their professionally guided tours during the whitewater season. They include Kings River Expeditions, Spirit Whitewater, and Zephyr Expeditions.

The companies generally take people of many skill levels. Teens are allowed to go, but it is best to check with the companies on children 12 years old and younger. In May and even June, the water can be quite cold, so wet suits are often recommended. The companies rent wet suits, life jackets, and often provide meals and overnight camping. The season stops when the snowmelt slows down—usually in late July or August.

Read and add comments about this page