[Fig. 38(1)] The Hiwassee Ranger District is known for its family float trips down the Hiwassee River; trout-fishing areas, including a trophy section; the scenic Coker Creek; hiking trails; and horse trails.

John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, walked along the Hiwassee River in 1867. In 1972 the Youth Conservation Corps and the Senior Community Service Employment Program built the 19-mile John Muir National Recreation Trail. Those walking the trail have opportunities to see songbirds, grouse, turkey, and beaver (Castor canadensis). Raccoon, fox, deer, and boar may be present but show themselves only to stealthy hikers.

The Hiwassee Ranger Station has brochures, maps, and books about the area. The Hiwassee Ranger District (about 86,000 acres) has more privately owned lands interspersed among the Cherokee National Forest (CNF) lands than the other districts.

Ayuwasiu, the Cherokee name from which Hiwassee was derived, means "meadow at the foot of the hill."

This popular east Tennessee river's headwaters are in the northwestern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains along the Appalachian Trail in northern Georgia. The Hiwassee courses through North Carolina and then turns west into Tennessee. The Hiwassee River drains a mountainous watershed of 750,000 acres in the Cherokee National Forest, Nantahala National Forest, and Chattahoochee National Forest. Because these lands are forested, the water flowing through the Hiwassee Ranger District is of good quality.

Rocks exposed along the river were formed of sediments that were eroded from highland masses into shallow seas that covered this area 800 million years ago. These layers of sediments formed sandstones and shales that were metamorphosed into quartzites and slates with inclusions of gold, garnet, quartz ruby, emeralds, and other elements and minerals.

About 250 million years ago, a slow uplifting and folding formed the Appalachian Mountains. The Hiwassee River and its tributaries began carrying the materials washed from their slopes. Erosion by the young Hiwassee River carved the steep gorge the river runs through today.

Archaeological evidence testifies that ancient people lived in the Hiwassee

Valley long before the Cherokees, Creeks, and other tribes came to the region.

Hernando De Soto, the Spanish explorer, and his men were reported to have traveled

along the Hiwassee River's banks in the summer of 1540. De Soto behaved as

Cortez did in Mexico and as Pizarro did in Peru, ransacking villages in search

of gold and taking supplies to sustain his quest.

Later, French and English explorers came, and then settlers. In 1835, the Cherokee were forced to surrender their homelands to the newcomers and, three years later, were removed. More Europeans moved into the area permanently.

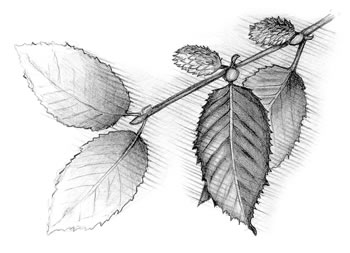

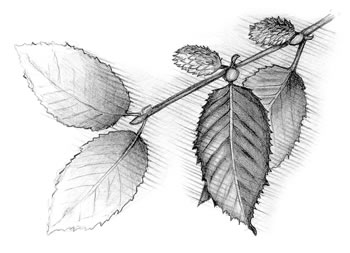

This land along the Hiwassee River, under the stewardship of the Indians, was lush. Forests of chestnut, poplar, oaks, pines, and hundred of other trees flourished along with thousands of other plants species. This abundant vegetation provided food and cover for wildlife—bison (Bison bison), elk (Cervus elaphus), turkey, deer, bear, and mountain lion (Felis concolor), also called puma, panther, or cougar.

The Indians may have cultivated portions of the Hiwassee River valley as long as 3,000 years ago. The first Europeans to enter the area saw the valley used for agriculture but the mountains were unchanged.

By the late 1800s, this country, new to the whites, was hungry for building materials. By the 1920s these mountains were cleared of timber, and the Hiwassee River was again carrying materials from erosion. The Forest Service moved into the region to manage the natural resources of the southern Appalachian Mountains. Reforestation began, and we have those results to enjoy today.

Families delight in rafting, canoeing, and kayaking on the Hiwassee River. The 12-mile run from Appalachia Powerhouse to US 411 bridge provides exciting whitewater experiences. Most of the river is easy to navigate on Class I water. Class I means there are few obstructions, small waves, and easily manageable rapids. The river also has Class II and III waters. Class II rapids are still considered easy to manage, but Class III rapids have waves high enough to swamp an open canoe and require complex maneuvering.

There are commercial outfitters under special use permit with the Forest Service to provide services on the river (see Appendix C).

[Fig. 38(2)] The Gee Creek Wilderness Area (2,573 acres) is located on the western edge of the Hiwassee Ranger District. It is bound on the west by Starr Mountain and on the east by Chestnut Mountain, and it lies about 9 miles southeast of Etowah. Gee Knob rises to 2,000 feet at the southeastern tip of the wilderness area.

The Gee Creek Wilderness Area's Starr Mountain was named for Caleb Starr. Caleb moved to Tennessee, then part of North Carolina, from Pennsylvania after the Revolutionary War. Starr married the granddaughter of Nancy Ward named Nancy Harlan. The Starrs, owners of Starr Mountain, grew wealthy raising livestock and amassing land that was under Cherokee jurisdiction.

James Starr, son of Caleb and Nancy, convinced President Andrew Jackson to give 640 acres to white settlers moving into the area. This, among other events, led to the federal government forcing the Cherokee to give up their homelands and move to Oklahoma. James Starr's plans went awry because the Starrs were part Cherokee and they too lost their lands to walk the Trail of Tears.

James Starr was killed for selling out the Cherokees. Another of Caleb's sons, Tom, became a murderous outlaw at the age of 19, revenging his brother's death. Caleb's grandson, Sam Starr became an outlaw riding with the infamous Younger gang. Sam's wife, Belle, also earned her place in history, becoming a better-known outlaw than all her relatives.

Gee Creek Wilderness Area became the CNF's first so designated area in 1975. Lying between two mountains, the gorge is surrounded by steep drops. The lower elevations contain rhododendron, hemlock, and poplar, and the higher elevations hold Virginia pine, red and white oaks, and hickory. The largest trees remaining in the area are in the Gee Creek gorge. Loggers took most of the timber from here within the last half-century.

[Fig. 38(2)] Gee Creek flows south through the gorge into the Hiwassee River, and Gee Creek Trail (#191) follows it. The trail was originally a path anglers made to get to the trout-rich waters.

Hikers will enjoy viewing and photographing two waterfalls and the remnants of an old concrete flume that was used in iron mining from 1825 to 1860 by the Tennessee Copper Company.

About 1 mile down the trail is a hemlock-encircled campsite between the creek and a 150-foot cliff with another waterfall nearby. (No overnight camping is allowed because this wilderness area is too small.) Just above the campsite is one of the largest hemlocks remaining in the gorge. Here is where many hikers turn around because there are few features farther along, there are more creeks to cross, and the trail wanes. Hikers should be careful about getting off the trail and going up the canyon side to avoid crossing the creek. The ground is unstable and dangerous.

[Fig. 38(3)] The John Muir National Recreation Trail (#152) follows the Hiwassee River upstream (east) from Childers Creek for 18.9 miles to FR 311 east of Coker Creek Scenic Area and TN 68. Muir walked along the north shore of the Hiwassee River in September of 1867, making a note in his journal on September 19 stating this was an impressive river with a fine forest, multiple falls, and forest walls as vine-draped and flowery as Eden.

Had he walked the banks in spring he would have seen many wildflowers in bloom, as hikers see today. Bloodroot, fire pink, trillium, trout lily, squaw root (Conopholis americana), bishop's cap, and wild ginger are among those in evidence.

The first 3 miles of the trail are easy going through a meadow, and then it passes between the river and high bluffs of metamorphic rocks consisting of quartz schist, mica schist, mica slate, and micaceous quartzite. The trail leads away from the river, where rhododendrons and hemlocks cover the bluffs, into a marshy area. At the end of the easy 3-mile section is Big Bend Recreation Area with water and sanitary facilities.

Big Bend takes its name from the sharp southerly bend in the river. The trophy trout section begins here and runs west to the L&N Bridge in Reliance.

Three miles farther is the Appalachia Powerhouse, which has drinking water and sanitary facilities. A suspension bridge hangs over the Hiwassee River. Although this is not part of the trail, it offers a good view of the river and its banks.

The trail continues along the river to the Narrows, where there are some interesting rock formations caused by erosion. In about 3 more miles the trail runs along the top of a bluff furnishing a spectacular view. Coker Creek joins the Hiwassee River just beyond the bluff. Primitive camping is allowed here near the Coker Creek/John Muir parking lot at the southern end of FR 22B.

The remaining 7 miles run along the river and through the forest of flame azalea, mountain laurel, and rhododendron that bloom in early summer. Many hikers forgo the last mile of the hike and stop at TN 68. The last difficult leg leaves TN 68 and ends at FR 311.

[Fig. 36(15)] To reach other interesting places and features in the eastern Hiwassee Ranger District, the route via TN 68 through Tellico Plains offers the best roads. Coker Creek Scenic Area is closer to Etowah as the crow flies than Tellico Plains, but the saying "you can't get there from here" applies unless you are willing to meander through the mountains on gravel roads.

Coker Creek Scenic Area (375 acres) is a small part of the Coker Creek valley, but it offers outstanding features including Coker Creek Falls; thick, lush forests of deciduous and evergreen trees with some old-growth hemlocks and white pine; wildflowers; and flocks of wild turkeys. Coker Creek flows into the Hiwassee River.

The community of Ironsburg near the headwaters of Coker Creek got its name from an ironworks built by the Cherokee before 1812. Carroll Ironworks later bought it from the Indians, and in the winter of 1863 General Sherman destroyed it.

Coker Creek was the site of a gold strike. When the discovery was made in 1820s, about the same time gold was found in northeast Georgia and more than two decades before the California strike, Coker Creek became a bustling place. Most of the mining ended by 1860, but visitors are welcome to shake a pan at local commercial mining establishments.

[Fig. 36(15)] Coker Creek Falls Trail (#183) begins at the northern end of the scenic area at the end of FR 2138. The roar of the waterfalls leaves no doubt as to which way to go. It is only 0.1 mile down the trail to the upper falls and about 100 feet farther to the main waterfall. The upper falls drops about 8 feet over a 35-foot width of the creek. Coker Creek Falls, the most spectacular of the series of waterfalls, cascades and drops about 20 feet in a block form.

Look for a spur path several yards downstream that leads south to Hidden Falls. Lower Coker Creek Falls, a short distance more downstream, drops about 10 feet in a tier form, and is the last significant waterfall along the creek.

The remainder of the trail goes along the creek, zigzags up a hill (follow the white blazes), descends, and ends at the Coker Creek Falls/John Muir parking lot, but don't stop. Continue following the creek to the Hiwassee River for a reward of scenic vistas, roaring rapids, clear pools, the large river, and metamorphic rock bluffs. The John Muir Trail crosses here.