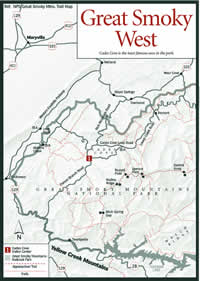

Among the park's many outstanding topographic features, perhaps the most intriguing are the strange, flat-bottomed valleys surrounded by mountains that are known as coves. Of the several that appear throughout the southern Appalachians, only one, Cades Cove, lies inside the park. The coves vary in size and shape but are considered to be of similar geologic origin.

For the simplest explanation, consider them as windows, formed when a hole or break appeared in the older, harder rock that overthrust the younger rock during a mountain-building period. Erosion, acting on the softer rock underneath eventually carved out large, deep openings, leaving the harder rocks standing as ridges on all sides. Early settlers were attracted to these coves, and not just because they were level lands. Coves also have limestone bottoms and contain an accumulation of soil and gravel washed down from the mountain slopes above. As a result, cove soils are deep, rich, and extremely fertile—an anomaly, since the soil in most mountain lands is thin and poor.

Even though Cades Cove was a part of the Cherokee Nation until the signing of the Calhoun Treaty in 1819, in which the Indians relinquished their claim to the territory, several grants were issued for Cades Cove land as early as 1794. However, the first legal land title was granted in 1819, and in all, 36 land grants were issued from that date until 1890.

In the meantime, the population of the cove grew rapidly. The first families moved in in 1820, and by 1830 records show 44 households and a population of 271. Until that time there were only Indian trails between the cove and the outside world, but between 1830 and 1840, five roads were opened.

By the end of the decade the numbers had increased to 70 households with 471 people. By 1850, there were 132 households and a population of 685, but a slump followed that reduced the numbers significantly during a 10-year period. Another influx of settlers occurred in the late 1800s, and in 1900 the population reached its all-time peak of 125 families and 708 people.

From that point, due to World War I, the great flu epidemic of 1917_1918, people leaving the cove for employment elsewhere, and the initiation of the park movement, the population gradually diminished. Once all of the land in Cades Cove was purchased, a few residents were allowed to remain as lease-holders, but as soon as they died or moved out, the Park Service destroyed evidence of all but a handful of their homesteads, intending to allow the valley to return to its natural condition. Not all of the homes were log cabins, and the lifestyles of most of the families were far from primitive.

A closer look at the history of Cades Cove reveals that it was much more civilized

than people outside the mountains might have imagined. There was a well-organized

local government, as well as schools, churches, general stores, blacksmith

shops, regular mail service, telephone communication, and even automobiles.

For many years Cades Cove wasn't well known because the valley was so prosperous that families could provide for their own needs. For many years the inhabitants were distant from any marketplaces and had little use for cash. They depended upon each other for the food and few comforts they enjoyed. Each household had its own vegetable garden, and they raised grain. Grain could be ground in tub mills into cornmeal and flour needed for the family's personal consumption. They also needed grain to feed their livestock, including the chickens and cows that supplied them with eggs and milk.

Grain was also used to produce moonshine whiskey, which continued to be made in the cove even after the government ceased to license distillers. There was also brandy distilled from fruit. Such spirits, along with apples (Malus sp.) and chestnuts, were items that were transported out of the cove and sold for cash in Maryville or Knoxville.

Today, Cades Cove is the most popular destination in the most popular park in the United States. The Cades Cove Campground, developed with bathrooms and 161 campsites, is open year-round. There's also a small general store, riding stables with saddle horses and guided tours from April to October, and a picnic area near the campground. The visitor center is located at Cable Mill about halfway around the Cades Cove Loop Road.

Each year more than 2 million people stream into Cades Cove to admire the sweeping views and get a look at what life in the Smokies was like in the old days. Also, the cove is a favorite wildlife viewing area since it's nearly impossible to travel the 11-mile loop road and not see deer, turkey, bear, or groundhogs. Other small animals and birds are common sights also.

The main purpose of the loop road is to allow visitors to see the old cabins, churches, barns, and other structures built by the original settlers and preserved by the Park Service.

The Cable Mill at the Cades Cove Visitor Center is a water-powered grist mill that is still in operation, and stone ground meal and other mountain products can be purchased at the gift shop. Living history demonstrations are held spring through fall at the complex and include the making of sorghum molasses, apple butter, and lye soap.

There are two one-way gravel roads leading out of the cove. To the north Rich Mountain Road leads to Townsend. To the south, Parsons Branch Road ends on US 129 near Calderwood Lake. Both are closed in winter.

Two gravel roads, Hyatt Lane and Sparks Lane, connect the northern and southern portions of the Cades Cove Loop Road. Both cross Abrams Creek, which offers excellent rainbow and brown trout fishing, and offer easy access by foot through the cove. Between the waterfall on Abrams Creek and the portion of the creek that flows through the cove, the Abrams Creek Trail travels downstream beside some very good rainbow and brown trout waters.

An excellent system of hiking trails surround the cove including self-guided nature trails and longer, more strenuous trails including one to Gregory Bald, a broad grass meadow known for its display of flame azalea (Rhododendron calendulaceum) in late June. There is also the Anthony Creek Trail that begins as an access road to the horse camp and travels along Anthony Creek on its way to the high country at Spence Field, Thunderhead Mountain, and Russell Field along the Appalachian Trail.

Numerous backcountry campsites in the vicinity are open year-round, and among them Cooper Road, Hesse Creek, Kelly Gap, Rich Mountain, Ace Gap, Anthony Creek, Beard Creek, Flint Gap, Rabbit Creek, and Scott Gap are available to horse parties with backcountry permits. Anthony Creek is a drive-in horse camp that can accommodate 12 horses and 12 people from April through October. The camps at Ledbetter Ridge and Sheep Pen Gap are rationed because of heavy use and require a phone call to the park's Backcountry Reservation Office.

For many years limited agricultural practices, including cattle farming, were allowed by permit, but present plans are to return to the patchwork of fields and grasses. Some fields will be cut and others burned, and native grasses from other areas of the cove will be planted in an effort to crowd out the fescue grass that was planted in the 1960s to graze cattle. No other agricultural practices will be conducted.

A long-time cattle farmer in the cove will be allowed to remain, but he is limited to 500 cattle, down from the previous 1,500, and upon his passing, grazing will be phased out.