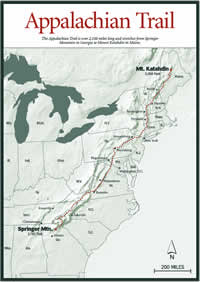

The Appalachian Trail (AT), America's most traveled long footpath, extends for 2,160 miles along 250,000 acres of the finest mountain terrain remaining in the eastern United States. Beginning at Katahdin, a granite monolith in central Maine, the white-blazed trail follows the crest of the Appalachian Mountains all the way to Springer Mountain in Georgia. Each year more than 3 million people hike all or parts of the trail.

For most of its journey through 14 states, the AT travels through public land. Virginia contains the longest section of the trail, 545 miles, while West Virginia contains the shortest, 26 miles. The lowest elevation is 124 feet above sea level near the Hudson River in New York, and the highest is 6,643 at Clingman's Dome in the Great Smoky Mountains. In the southern Appalachians, most of the trail passes through deciduous, hardwood forests, although spruce-fir stands are encountered at higher elevations. There are also balds and large areas blanketed with laurel and rhododendron thickets. In the spring a variety of wildflowers can be seen: several kinds of trillium and violets, bloodroot (Samguinaria canadensis), crested dwarf iris (Iris cristata), mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum), jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), flame azalea (Rhododendron calendulaceum), and numerous other. There are also spring displays of serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea), dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), and redbud (Cercis canadensis). In the fall, the many kinds of hardwoods provide superb color displays.

The initial proposal for such a trail was made by Benton MacKaye, a regional planner from Shirley, Massachusetts. MacKaye published an article in the October 1921 issue of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects entitled, "An Appalachian Trail, a Project in Regional Planning." The article described a vision of a footpath along the entire Appalachian ridgeline.

MacKaye's challenge ignited interest. At the time, almost all of the hiking clubs that could assist in such a venture were east of the Hudson River, and there were existing trail systems that could be incorporated into the AT. These systems included a series of trails in New England maintained by the Appalachian Mountain Club and the 130-mile Long Trail being developed in Vermont by the Dartmouth Outing Club. All of the efforts to build an AT were consolidated in 1925 with the formation of the Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC), a nonprofit educational organization of individuals and clubs of volunteers dedicated to managing, maintaining, and protecting the AT and its adjacent lands.

Arthur Perkins, a retired judge from Hartford, Connecticut, provided additional momentum to the trail movement by persuading groups to locate and cut the designated footpath through the wilderness, especially in the South where few trails and fewer clubs existed. More progress followed when Perkins interested Myron H. Avery, a Washington, DC attorney, to assist in the project. Avery enlisted the aid and coordinated the work of hundreds of volunteers who completed the trail on August 14, 1937, when the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) opened the last section.

That same year, an ATC member successfully proposed a plan for an Appalachian Trailway that would set apart an area on each side of the trail. The plan culminated in 1939 with an agreement between the National Park Service (NPS) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). The protection would extend 1 mile on each side of the Appalachian Trailway, no new parallel roads would be built, and no timber cutting would be permitted within 200 feet of the trail. Similar agreements creating a zone 0.25 mile in width were signed with most states along the AT's length.

A national system of trails was established by Congress in 1968, and the Appalachian Trail was included. The act directs the secretary of the interior, in consultation with the secretary of agriculture, to administer the AT primarily as a footpath and to protect it from incompatible activities. Supplemental agreements in 1970 among the NPS, USFS, and the ATC established the specific responsibilities of these organizations. Then in 1978 the slow progress of federal efforts led Congress to strengthen the National Trails System Act with amendments that emphasized the need for protecting the AT and set aside $90 million for acquiring a corridor through the lands outside the NPS and USFS lands. The acquisition program is scheduled to be completed in 2000. In 1984, the Interior Department formally delegated the responsibility of managing these AT corridor lands to the ATC.

The Conference, with 4,000 volunteers in 31 independent local clubs, plays the major role in maintaining the footpath, and the ATC publishes information on constructing and maintaining hiking trails, official AT guides, and general information on hiking and trail use.

Most trail guidebooks, including the Appalachian Trail Guide to Tennessee-North Carolina published by the ATC, cover the Tennessee and northwestern North Carolina sections of the AT together since the trail meanders back and forth over the border of these two states as it travels north/south. Tennessee and North Carolina offer a combined 376 miles of trail, much of it along ridgecrests above 5,000 feet. This portion of the AT offers some of the best wilderness and primitive areas along the trail's route as well as incredible scenic vistas from the high peaks.

Much of the trail in this region exists within the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee, the Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina, and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. This public ownership of trail lands ensures the AT's protection and improves hikers' chances of seeing a great variety of plant and animal life. In the Great Smoky Mountains National Park alone there are more species of trees than in all of Europe. Animals along the trail range from woodchucks, salamanders, and turkey vultures, to moles, mice, and skunks.

For more information: Appalachian Trail Conference, PO Box 807, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425-0807. Phone (304) 535-6331.