The

Nantahala Basin

The

Nantahala Basin  The

Nantahala Basin

The

Nantahala Basin Rivers in the Nantahala and the Tallulah basins, separated from each other by the Eastern Continental Divide, run in opposite directions. Water flowing north in the Nantahala follows a much longer path via the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, while water in the Tallulah Basin reaches the Atlantic more directly via the Savannah River. Because the route to the Atlantic is a shorter, steeper one, downcutting is heavier on the south side of the Blue Ridge. This may be one reason why the Tallulah River is nearly 1,000 feet lower than the bed of the Nantahala River.

The Nantahala watershed has an extensive system of trails of different lengths and varying degrees of difficulty. There are at least three horse trails and a special horse camp. There are fascinating plant communities, including bogs and some virgin forest.

Because of its soils and elevation, the Nantahala watershed had original timber of a size and density that brought visitors from as far away as Asheville, even when virgin timber was widespread.

The

area was logged until the 1920s. Ritter Lumber Company had its logging camp

where the main campground for the area is today; and at Rainbow Springs [Fig.

34(2)], Ritter had a band-saw mill to saw the huge trees. Narrow-gauge railroads

ran up and down the Nantahala River and went up its tributaries until stopped

by waterfalls. The route of the dismantled railroad is marked on topographic

sheets (USGS 1:24,000 map series: Rainbow Springs quadrangle).

The

area was logged until the 1920s. Ritter Lumber Company had its logging camp

where the main campground for the area is today; and at Rainbow Springs [Fig.

34(2)], Ritter had a band-saw mill to saw the huge trees. Narrow-gauge railroads

ran up and down the Nantahala River and went up its tributaries until stopped

by waterfalls. The route of the dismantled railroad is marked on topographic

sheets (USGS 1:24,000 map series: Rainbow Springs quadrangle).

The Nantahala is known for large brown trout, and its headwaters still support native brook trout populations. It has also been a black bear refuge for years. An additional attraction is Nantahala Lake, into which the Nantahala River flows. At 3,000 feet, it is one of the highest large lakes in the mountains.

Directions: Go north on US 441 to Franklin, NC; turn left onto US 64; go 12 miles and turn left onto old US 64; go 1.8 miles to Wallace Gap [Fig. 34(1)] and turn right onto FS 67, which is the road into the basin.

For those interested in combining driving and short walks, there is a marvelous tour of the area to see an immense poplar tree, two waterfalls, and vistas from Pickens' Nose.

From the turnoff at Wallace Gap (see directions above), go .4 mile to a parking area on the left. It is directly adjacent to the Appalachian Trail (AT), so that one can park here for walks in either direction on the AT. This is also the trailhead for the short (1.4-mile round-trip) walk on a graded trail to the John Wasilik Memorial Tree, which is the second largest yellow poplar in the United States. It is 8 feet in diameter, 25 feet in circumference, and was 135 feet tall until topped by a storm. The tree is in one of a series of north-facing coves, called the Runaway Knob Special Interest Area, where over 100 plant species have been identified. Lying between 3,200 and 4,400 feet, the 140-acre area is the location of an exceptionally beautiful spring wildflower display. The forest below the Wasilik Poplar contains North Carolina's largest reproducing population of the rare yellowwood tree, which occurs in only a few localities in Georgia and North Carolina.

Continue about 1.1 miles on FS 67 to a fork; take the left fork, FS 67B, about .2 mile to the Backcountry Information Center. In the valley upstream are flat areas of floodplain and alluvial fill with some open areas [Fig. 34(10)]. Some of these are wildlife openings and others are rare wetland bogs—some as large as 20 acres, lying between 3,400 and 3,500 feet in elevation. This is the second largest bog complex in western North Carolina and the subject of paleobotanical studies of the peat underlying them. The bogs should not be entered.

Continue 4.7 miles on FS 67 to the parking area for Big Laurel Falls [Fig. 34(24)] (1.2 miles round-trip), an easy hike for the whole family. This is also the trailhead for the Timber Ridge Trail [Fig. 34(27)], which connects with the AT.

Continue on FS 67 for .8 mile to the pull-off area for Mooney Falls. The trail is a .2-mile round-trip to the falls [Fig. 34(21)].

Continue on FS 67 until its intersection with FS 83. Turn right and continue past Mooney Gap [Fig. 34(18)], a station for acid rain studies by Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory, and a crossing of the Appalachian Trail. At .7 mile past Mooney Gap, park on the north side of the road and walk south 1 mile to Pickens' Nose (5,000 feet). Vistas are to the east, west, and south into the Betty Creek Basin. An optional walk is to Albert Mountain. Backtrack on FS 83 as far as it will go north, then hike up to the Albert Mountain fire tower [Fig. 34(12)], which provides an exceptional 360-degree view. (Pickens' Nose and Albert Mountain can also be reached by Buck Creek Road through the Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory off US 441 north of the Georgia/North Carolina state line). At Big Spring Gap, the Pinnacle Mountain Trail [Fig. 34(9)] descends to the northeast.

The best virgin timber in the area lies above the falls of Kilby Creek [Fig.

34(28)], a challenge for wild-country devotees. This is largely cove hardwood

with big

hemlock-rhododendron forests along the streams. Above the falls there are brook

trout, the only native species. This is wild and rough country, a true wilderness.

Visitors to it should take no chances.

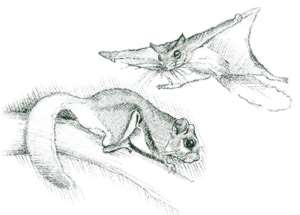

[Fig. 34(15)] At 5,499 feet, this is the highest peak in the Nantahala Mountains. Its Indian name translates literally "the place where man stood." Cherokee mythology relates the story of a winged monster that stole a child and carried him to the cliffs on top of the mountain [Fig. 34(16)]. The Indians prayed to the Great Spirit, who answered their prayers by sending a lightning bolt that destroyed the monster and the trees on the summit, but the lightning also killed a lone Indian sentry and turned him to stone.

The easiest way to reach the summit is via US 64 and FS 71, a long gravel road to Deep Gap [Fig. 34(14)]. Along this road is dense roadside growth of an extremely primitive plant, a species of horsetail, or scouring brush, whose silica content was useful to the early settlers for scrubbing pots. From Deep Gap it is a 2.5-mile walk to the summit, climbing 1,200 feet and passing a good spring and shelter about one-third of the way up. The first large northern loop of this trail goes over and around a flat, wet, sheltered ridge with deep, stable soil, which may explain the white oak ridge forest here with flame azalea and fern understory. The trail also shows the effect of exposure. The white oak goes downslope only 30 feet to the more exposed east, but it goes down the western slope 120 feet. The summit of Standing Indian is heath or shrub bald, principally of purple rhododendron. Formerly, a fire tower stood here and a telephone wire ran up from the Tallulah Valley. The Fraser fir nearby were planted.

There are two springs northeast of the summit. South of the ridgeline in the ridge forest (not on the Appalachian Trail) are some pits [Fig. 34(17)], relicts of the period when mica was mined in the area. These may be discovered by diligent explorers. The Appalachian Trail here tunnels through rhododendron and flame azalea and is quite dramatic in early summer. Traveling on down the 1.5-mile ridgeline, one sees Little Bald directly south and passes through several environments, principally red oak ridge forest and areas of shrub bald vegetation [Fig. 34(20)] dominated by mountain laurel, with some purple rhododendron. Some drier areas have grasses, while other almost-bare soil areas are covered with a rare tundra species—the three-leaved cinquefoil, a threatened species at the southern periphery of its range. The effects on the soil of ice heavage—that is, the repeated freezing and thawing of the earth—and the results of wind shear on the shrubs are evident.

There has been much scientific debate on the origin of balds such as those which cap many of the Appalachians' highest peaks. Here on the southwest slope, one can see the bald area grading into dwarf northern red oak–evergreen heath, which within several hundred feet grades into northern red oak–deciduous heath (azaleas and blueberries). On the opposite side (the northeast slope), the bald areas grade into a beautiful northern red oak-fern community that in turn grades into a northern hardwood forest. To the west lies Big Scaly (5,200 feet) [Fig. 33(23)] in the immediate foreground. The Girl Scouts had a connector trail [Fig. 33(19)] leading down to Beech Creek through the rhododendron and virgin red oak ridge forest with flame azalea understory, but the entrance is difficult to find. There are two other accesses to Beech Creek—one an old log road, the other a steep trail (see Tallulah Basin)—both beginning at Beech Gap. The upper portion of the Big Indian Loop horse trail passes through a succession of cove hardwoods, northern hardwoods, and boulderfields. Loop-trail possibilities are numerous. If two vehicles are available, a shuttle can be set up. For example, one vehicle may be left at Deep Gap [Fig. 34(14)] and another at either Standing Indian Campground or at the Beech Gap Trail junction with FS 67. Then one could hike to the summit of Standing Indian and down the Lower Ridge Trail [Fig. 34(8)], or down the long spine of Standing Indian to Beech Gap [Fig. 34(25)] and down the Beech Gap Trail [Fig. 34(26)], with a side visit to the Kilby Creek virgin forest [Fig. 34(28)].

Hiking

Trails in the Nantahala Basin

Hiking

Trails in the Nantahala Basin There are seven trails from the valley up to the Appalachian Trail (AT). They can be combined in a number of ways to create interesting loop hikes. One warning: the weather here can change rapidly. In particular, the hiker should beware of afternoon thunderstorms on the high ridges and peaks in the summer months.

KIMSEY CREEK TRAIL TO STANDING INDIAN. 10 miles round-trip. One favorite hike is to walk to Standing Indian Mountain starting from the Backcountry Information Center on the Kimsey Creek Trail [Fig. 34(6)], a wonderfully varied path along creeks and through wildlife meadows with many wildflowers. The trail connects with the AT at Deep Gap [Fig. 34(14)]. Follow the AT to the top of Standing Indian, which is a strenuous climb. There is a junction at which one spur goes from the AT to the top for a vista. Return to the AT and continue a very short distance (10 yards or so) to the Lower Ridge Trail [Fig. 34(8)], which returns to the Backcountry Information Center in 4 miles.

LOOP TRAIL. 10.9 miles round-trip. Another loop might be to hike up the AT on the Long Branch Trail from the Backcountry Information Center (1.9 miles). Hike south (to the right) 3.1 miles on the AT to the Albert Mountain lookout tower (5,280 feet) [Fig. 34(12)] for views in all directions. Continue on the AT. .3 mile to Bearpen Gap Trail [Fig. 34(13)]; descend 2.4 miles on Bearpen Gap Trail to FS 67/2; turn right and return 3.2 miles to the Backcountry Information Center.

PARK CREEK AND PARK RIDGE TRAILS. 10-mile loop. This interesting hike away from the AT (which means it is less crowded) combines the Park Creek [Fig. 34(3)] and Park Ridge trails [Fig. 34(4)]. One begins at the Backcountry Information Center. This beginning is the same as for the Lower Ridge Trail and the Kimsey Creek Trail. About .5 mile from the bridge in the campground, the Park Ridge Trail goes left up the ridge and climbs to Park Gap [Fig. 34(7)] at FS 71/1. Cross the road and descend on Park Creek Trail along a lovely stream to the Nantahala River; turn right and walk about 1.5 miles to the junction with Park Ridge Trail and retrace the path to the Backcountry Information Center.

ACCESS TO DAY HIKES. Another access to day-hike trailheads is from FS 71/1. Take US 64 west from Franklin, past the turnoff at 12 miles onto old US 64; go about 2.5 miles and turn left onto FS 71; go about 2.5 miles to reach Park Gap [Fig. 34(7)]; park in this area and walk the Park Ridge and Park Creek loop trails. Driving another 3 miles past this parking area, one reaches the end of the road at Deep Gap. Here is access to the Kimsey Creek Trail, the AT east to Standing Indian Mountain (2.8 miles one-way), a primitive trail south to the Tallulah River, and the AT west to White Oak Stamp and Bly Gap.

THREE-DAY WALK. 24 miles. A good backpacking trip starts at the Backcountry Information Center, on the Long Branch Trail to the AT. Turn right (south) onto the AT and follow it over Albert Mountain [Fig. 34(12)], through Bear Pen Gap, over Big Butt, down to Mooney Gap [Fig. 34(18)], passing Carter Gap and Beech Gap [Fig. 34(25)], climbing Standing Indian Mountain, and descending to Deep Gap [Fig. 34(14)]. Turn right on Kimsey Creek Trail and return to the Backcountry Information Center. This is a pleasant three-day walk. There are shelters at Big Spring Gap, Carter Gap, and Standing Indian (near Deep Gap). This is a popular loop, so shelters may be filled. Walked in early June, the stretch up Standing Indian Mountain is a botanical garden. The Catawba rhododendron and mountain laurel arch over the trail to form a floral tunnel.

OTHER TRAIL POSSIBILITIES. Many other combinations are possible using the following trails in conjunction with the Appalachian Trail: Kimsey Creek Trail [Fig. 34(6)], Lower Ridge Trail [Fig. 34(8)], Long Branch Trail, Beech Gap Trail [Fig. 34(26)], and Betty Creek Gap connector [Fig. 34(22)].

HORSE TRAILS IN THE NANTAHALA BASIN. A series of special horse trails [Fig. 34(5)] covers the Long Branch and Hurricane Creek watersheds. There is a horse camp near the mouth of Hurricane Creek [Fig. 34(11)]. For further information, ask the ranger. There is also a long horse trail on the east slopes of Standing Indian.

Map References: USGS 1:24,000 series: Prentiss–Rainbow Springs.

Read and add comments about this page