Tioga

Road

Tioga

Road  Tioga

Road

Tioga

Road [Fig. 37] Tioga Road, or Highway 120, is the longest trans-Sierra route and widely considered the most scenic. It runs 46 miles from Crane Flat, elevation 6,192 feet, to Tioga Pass, elevation 9,945 feet at the Yosemite gate.

Travelers can see an array of glacially carved mountaintops, domes, spires, and lakes, along with alpine vegetation and meadows. The tiny remnants of once mammoth glaciers can be seen in the cirques along Mount Lyell, Kuna Crest, and Mount Conness. The glaciers are mostly above 11,000 feet.

There are many places to stop, look, and explore this vast high country. Many trailheads depart from Tuolumne Meadows, a kind of Mecca for high Sierra backpacking. Other locations for camping or other recreation include White Wolf, Tenaya Lake, and May Lake.

Stop at Olmsted Point, 9 miles from the Tioga Pass gate, and look at the view. Half Dome is in the distance to the south. The Cathedral Range is just to the east. But, even more impressive, the granite landscape spreads out for miles in all directions, giving a hint of what things looked like about 55 million years ago.

At that time, the granite already had risen, but it had been eroded to the basic form that can be seen today. Many geologists believe it was several thousand feet lower then, and the erosion processes were carrying bits and pieces of it in rivers into California's 400-mile-long Central Valley.

Volcanic eruptions took place about 20 million years ago, and the faults that caused the Sierra to lift probably began about 10 million years ago. Before tons and tons of ice covered the Tioga high country about 3 million years ago, it already had risen dramatically from the faulting.

How fast could the area rise? The eastern side of the range rose more than 13 feet in a single earthquake recorded in 1872. With such events continuing every few centuries, it is conceivable that the Tioga high country could be an average of 15,000 feet high in the next few million years. That would make it higher than 14,498-foot Mount Whitney, the tallest mountain the contiguous 48 states.

But the grand scale of Tioga often becomes obscured in Yosemite because of politics and human history. The road has been mired in political infighting for decades.

Business

owners on the Sierra's east side have come to rely on the road to deliver

tour buses and customers to their communities, which include Bishop, Lee

Vining, and Mammoth Lakes. The National Park Service must close the road

each autumn with the first substantial snowfall. It does not reopen until

spring when the road can be cleared of snow. But east-side business owners

believe the park service is too slow to reopen the road. Park service officials

defend their schedules, saying they must be sure the road is safe.

Business

owners on the Sierra's east side have come to rely on the road to deliver

tour buses and customers to their communities, which include Bishop, Lee

Vining, and Mammoth Lakes. The National Park Service must close the road

each autumn with the first substantial snowfall. It does not reopen until

spring when the road can be cleared of snow. But east-side business owners

believe the park service is too slow to reopen the road. Park service officials

defend their schedules, saying they must be sure the road is safe.

It is all part of Tioga's human history, which goes back about 2,000 years when Native Americans from the western slope, Miwok, traveled across the Sierra to trade berries, beads, and baskets with the eastern tribes, the Mono. The Mono would trade buffalo robes, salt, and obsidian, among other things.

Miners and others completed the original dirt road in the 1880s near the current Tioga alignment. The road was rebuilt and paved in the late 1930s and 1940s. The road was completely realigned and rebuilt again at a cost of almost $7 million in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Critics say the road should never have been constructed on the south side of a slick granite face at Olmsted Point. Officials built the road there because they wanted the stunning view from Olmsted. However, when snow-clearing operations take place each spring, Olmsted is notorious for being avalanche-prone. In the mid-1990s during snow plowing, a massive block of ice crushed a bulldozer, killing a park employee.

Such political battles have always been a part of Yosemite. People see the park passionately from many viewpoints—some emphasizing preservation, others pushing to open it for more people to see.

Between the politics and the geology, there is an interesting collection of vegetation at these high elevations, particularly in the meadows. Tuolumne Meadows, for instance, is a place where sod-forming sedges and grasses congregate.

Snow buries the high country meadows in late fall, winter, and spring. As it melts in June and July, swampy areas form where the sods grow. Probably the most common sight is the alpine sedge (Carex subnigricans), along with the Brewer's shorthair grass (Calamagrostis breweri). Visitors also will see such herbs as dwarf lewisia (Lewisia pygmaea), alpine goldenrod (Solidago multiradiata), and Lyall's lupine (Lupinus lyalli).

Shrubs are not generally abundant in this alpine environment. Near Tioga, people can find red mountain heather (Phyllodoce breweri) or dwarf huckleberry (Vaccinium nivictum), but these plants do not grow very large.

Birds, insects, and small creatures, such as chipmunks and pika (Ochotona princeps) are among the wildlife in the higher elevations around Tioga. Pika, though they look like rodents, are related to rabbits. They avoid human contact, living under rockslides.

The yellow-bellied marmot can grow big and fat here because people feed it. Park service officials continually warn visitors not to feed wild creatures. Often, it means the creatures will become dependent on human food and eventually die when humans leave.

The porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) is known to wander through the alpine meadows. It prefers to be in a forest around trees, but hikers do see porcupine in the Tioga area. Porcupine Flat along Tioga Road is at 8,550 feet. There is no indication in historic records that porcupine lived here, but it was known as Porcupine Flat as far back as 1863.

For those entering the park from the east, through the Tioga Pass Entrance Station, the National Park Service has recently replaced the 1,000-pound gates that once hung at the entrance. The new gates are replicas made of lodgepole pine wood and granite.

[Fig. 37] The trails and vistas from Tuolumne Meadows make it a worthy stop for just a half hour of picture taking or several days of backpacking. This meadow area is the largest of its kind in the Sierra, stretching for hundreds of acres as a shorthair carpet of resilient sedge and grasses at 8,600 feet and higher.

The glacial history would fill a textbook. Glaciers stretched over the expanse of the meadows because they were not limited to a streambed or canyon. They created features that are not commonly found in many parts of the Sierra.

Such features include the roches moutonnées, or "rock sheep" in French. They are rounded rocks that resisted the erosion of the glacier as it passed. There are small versions of them in many places around Yosemite, including Tuolumne Meadows. French geologist Horace Benedict De Saussure coined the name roches moutonnées.

Hikers can see Lembert Dome rising above the meadow. Climb up to see parts of the dome, which shines in the sun because of the polishing action of the ice about 145,000 years ago.

Shorthair sedge (Carex exserta) dominates the vegetation found in the meadows. Other sedges include beaked sedge (Carex rostrata) and black sedge (Carex nigricans). It stands up to frost and cold at this elevation. Look also for grasses, such as the spiked trisetum (Trisetum spicatum), Hansen's bluegrass (Poa hanseni), and gray wild rye (Elymus glaucus). Besides surviving the cold and snow, this vegetation does well in dry soils, particularly in late summer.

The meadow will fill with snowmelt briefly in late June and July. In the swampy conditions, the snow mosquitoes (Aedes communis) thrive. They are often seen in clouds—usually surrounding unfortunate hikers and backpackers. Smear on repellents and sleep in tents with screens to avoid becoming a blood meal. However, it is almost impossible to avoid being bitten in late June and July.

Hikers and backpackers know Tuolumne Meadows as a kind of high country oasis. It is a place where they can get food, a shower, and even a tent with a bed. Tuolumne Meadows is one of the first major stops along the John Muir Trail for backpackers who begin at Happy Isles in Yosemite Valley.

Many hikers choose to park their cars in the valley and ride a shuttle bus to Tuolumne Meadows. From the 8,600-foot meadows, they hike back down to the 4,000-foot-elevation valley—a much easier trip than vice versa. Often, they take the Muir Trail, or they stop at another place along Tioga Road and hike back into the valley. The vistas are incredible, especially when a lot of water is flowing in late June and July.

The subalpine wildlife in this region includes the Yosemite toad (Bufo canorus), which is most likely to appear during wet times in the meadows. It usually hibernates beneath the snowpack and makes its appearance in May or June. Listen for a chorus of singing around warm, shallow pools of water.

For winter sports enthusiasts, cross-country skiing along Tioga Road can bring experienced skiers all the way to Tuolumne Meadows. Always check with the rangers before embarking on such a trip, however. Blizzards can move in very quickly above 7,000 feet in Yosemite or anywhere else in the Sierra.

[Fig. 37(1)] The view of the Cathedral Range directly south of Lembert Dome is spectacular. The smooth surface of the dome was created by glacial action. The dome is sometimes mistaken for a large roche moutonnée, but that is not what it is.

A true roche moutonnée has been completely overridden by ice, and Lembert Dome was merely shaped and polished by glaciers. For examples of giant roches moutonnées, go to Little Yosemite Valley and see the Liberty Cap.

The trail to Lembert Dome forks after 0.1 mile. Take the right fork and begin the short ascent of the dome. The trail will disappear on the granite after about 0.8 mile, but it is not difficult to see where to go.

The trail leads through lodgepole pine, which is a fairly typical tree to find in the forest surrounding a subalpine meadow such as Tuolumne Meadows. Notice the limbs of larger trees and the entire trunks of smaller ones are bent at odd angles from the heavy snowfall. Some areas experience avalanches.

Lembert Dome is named after a sheepherder who was tragically slain in the 1890s. Jean Baptiste Lembert also was somewhat of a naturalist who spent time in Tuolumne Meadows during the summer, living in a cabin. His body was found in a cabin near Yosemite Valley, and the case was never solved.

The hike to the dome is an easy morning walk. Some people like to stop for a picnic at the top. Don't get too close to the summit if you have difficulty with heights.

[Fig. 37(2)] The jagged granite atop Cathedral Peak is a sight waiting for anyone who makes the ascent to the Cathedral Lakes. The glacial lake is usually reached in a day hike, though many people prefer to backpack the trail and camp around the lake.

The

trail takes hikers past erratics, boulders left behind after glaciers melted.

Note the smooth appearance of the granite bedrock, which was scoured by

passing glaciers.

The

trail takes hikers past erratics, boulders left behind after glaciers melted.

Note the smooth appearance of the granite bedrock, which was scoured by

passing glaciers.

Besides lodgepole pine, fir trees are found as hikers climb higher on the trail. Both red fir and white fir occur as hikers reach elevations that reveal a view of Fairview Dome, another glacially polished feature.

Some prominent shrubs found on the hike include white mountain heather (Cassiope mertensiana) and bush cinquefoil (Potentilla fruticosa). In July and August, wildflowers found along the trail include the California valerian (Valeriana capitata), Bigelow's sneezeweed (Helenium bigelovii), and Sierra butterweed (Senecio scorzonella).

If a day hike is the plan, it's a good idea to start early and take it slow, especially for those coming from a sea-level area the day before. The hike begins above 8,000 feet, and even the fittest hikers experience shortness of breath unless they are acclimated to this elevation.

[Fig. 37] The Tenaya Lake/Olmsted Point area is considered the main stop in Yosemite for anyone who has very little time to spend. From Olmsted, visitors can look down Tenaya Canyon to the south, toward Half Dome and Little Yosemite Valley, near Yosemite Valley. At Tenaya, visitors can fish, hike, and see a glacially carved lake up close. The surrounding granite is one of the best examples of glacial polish in the park.

The lake was created when a glacier dug down in the Tuolumne Canyon to make a depression in the granite bedrock about 15,000 years ago. The receding ice left one of the larger and more scenic lakes in Yosemite National Park. Tenaya Lake, at an elevation of 8,149 feet, is about 1 mile in length and 0.5 mile in width.

The lake spreads in full view south of the road, attracting flocks of visitors to picnic and see the granite peaks and domes surrounding it. It can be seen from Olmsted Point, which is about 2 miles to the west on Tioga.

Tenaya Lake is where Chief Tenaya of the Ahwahnachee tribe was captured in 1851. The Mariposa Battalion caught Tenaya and escorted him down to Yosemite Valley. The lake is named for the chief. Tenaya Lake was known as "Lake of the Shining Rocks" to the tribe, because of the smooth, polished look that remained after the glacier created the lake basin.

Olmsted Point is named after Frederick Olmsted, the well-known landscape designer who directed the construction of New York's Central Park. Olmsted was the chairman of Yosemite's first Board of Commissioners in the nineteenth century.

The spectacular southeast-facing granite near Olmsted has been the source of much debate and danger over the past 30 years. Thick blocks of ice freeze at an angle on the rock during winter. In spring, as the ice melts, small sections beneath the ice liquefy and begin sending water out from beneath the ice block. During cold spring nights in May, it often refreezes, only to begin thawing again the next day.

The several tons of ice can slide without warning onto Tioga Road. A road-clearing worker was killed in a bulldozer in such an avalanche during the mid-1990s. Park officials have since hired an avalanche consultant who uses dynamite to blast unstable sections down from the dome.

On the eastern side of the Sierra, merchants and business owners wait for the road to open and bring them the tour buses that will keep their economies alive. So, each year, park officials must balance the goals of safety and access. The controversy ignites because east-side interests believe the park is being too cautious and too slow about opening the road.

Once visitors are allowed on the road, usually in late May or June, they will see Mount Conness at 12,600 feet to the east of Olmsted and Fairview Dome to the south. Among the subalpine vegetation is the mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana), a tough tree that thrives in areas where snow piles deep. There are not many places in Yosemite where visitors can drive past mountain hemlock. Usually, it is best seen on a hike in the high country.

[Fig. 37(3)] The area is popular because of its easy access: Visitors can drive most of the way to May Lake. The 1.1-mile hike to the lake from the parking lot is scenic and not too challenging. It is also a historic trail. The route is the part of the old Great Sierra Wagon Road, which preceded Tioga Road. Travelers used the route extensively in the 1880s going from east to west through Yosemite.

The lake is just below the approximate geographical center of Yosemite—Mount Hoffmann, the 10,850-foot peak that scientists believe jutted out above the last glacier about 12,000 years ago. The mountain was named after Charles Hoffmann, a topographer who passed through the area in the 1860s with the geological survey led by geologist William Brewer. May Lake is a stopping point along a 50-mile high-elevation route that circles Tuolumne Meadows. It is one of five High Sierra camps along the route. Each of the High Sierra camps is about 10 miles or a one-day hike from each other. Hikers can rent tent cabins, buy food, and rest amid the lodgepole pine and the red mountain heather.

Take time to stop along the way; turn around and see Clouds Rest to the south. The 9,925-foot summit is often surrounded with clouds in spring and fall.

[Fig. 37(4)] The trail is busy but rewarding for those who want a picnic alongside one of the three Sunrise Lakes. They include lower, middle, and upper lakes. All have views of the glacially shaped landmarks and erosion process—exfoliation—that continues to change their faces.

This route is filled with mosquitoes in June and part of July. Usually, the mosquitoes are out for their blood meals in the morning and early evening hours. Put on the repellent along with the sunscreen and hike this during the warmer parts of the morning and afternoon.

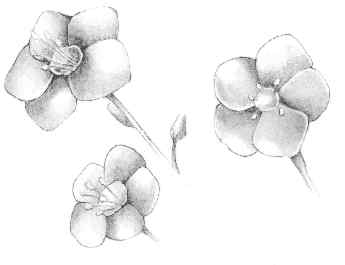

The wildflowers at this elevation can bloom in July and August. Look for bud saxifrage (Saxifraga bryophora), Nuttall's gayophytum (Gayophytum nuttallii), and western blue flag (Iris missouriensis). The displays can be wonderful for those who like to photograph wildflowers.

This hike also will give amateur botanists the chance to see white mountain heather (Cassiope mertensiana), a late-summer delight to see at high elevations. The wiry stem systems intertwine and create dense mats that are highlighted with bell-like flowers. They grow around rock ledges, and they are not generally visible from roads in Yosemite.

[Fig. 37(5)] The view of Half Dome from North Dome makes this day hike worth the effort. Half Dome looms southeast of North Dome, separated perhaps by only 2.5 miles with Yosemite Valley yawning below and the glacially scarred Tenaya Canyon to the northeast. It almost looks as if you can reach out and touch Half Dome.

The lodgepole pine in the area is a favorite food for the American porcupine. The porcupine feed on the inner bark of the lodgepoles. They feed at night, making a soft grunt or groaning "nuh" as they move about. From North Dome, most of the geologic features at the rim of Yosemite Valley are visible, including Illilouette Fall, Clouds Rest, Glacier Point, Sentinel Rock, Three Brothers, and El Capitan. In the valley, the Ahwahnee Hotel is a recognizable landmark. The views of wildflowers in meadows near Porcupine Creek are another attraction on the hike. Look for creeping sidalcea (Sidalcea reptans), blue-eyed mary (Collinsia torreyi), and alpine lily (Lilium parvum). Sedges in the area include black sedge and beaked sedge.

The hike is not considered difficult, but some people are susceptible to elevation sickness. The symptoms include a pressure behind the eyes, headache, and dizziness. Severe forms of it can force people to simply stop hiking, rest, and turn around. North Dome, at 8,522 feet, probably would not cause elevation sickness for most people.

Read and add comments about this page