No force outside nature has shaped the destiny of the Great Valley and the Tennessee mountains more than the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). It all began over six decades ago. In 1933, only 37 days after he was sworn into office, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress to create TVA. "It should be charged," he said, "with the broadest duty of planning for the proper use, conservation, and development of the natural resources of the Tennessee River drainage basin and its adjoining territory for the general social and economic welfare of the nation." On May 18, 1933, Congress approved his proposal.

It was an idea that had solid background. President Theodore Roosevelt and his conservation adviser, Gifford Pinchot, had worked together to establish the national parks system and the U.S. Forest Service in an effort to conserve the nation's natural resources. However, the administrations that followed failed to maintain the national policy to conserve the nation's natural resources, and there was nationwide exploitation of them, including depletion of the once-fertile agricultural lands that led to the disastrous dust bowl conditions.

The TVA plan was broad, focusing principally on building a series of dams in the Tennessee River system for flood control and power production, but also aimed at improving the social and economic welfare of the people. By the 1930s, the valley was in sad shape, even by Depression standards. The soil on most of the land was eroded as a result of being farmed too much for too long. The timber had been cut, and what woodlands remained were regularly burned for grazing. Families that once prospered had fallen on hard times. Timber companies had ravaged the mountains to the east, and to the west, the Cumberland Plateau had been stripped of coal, iron, and timber.

Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska, the most powerful proponent of the TVA plan, was determined to gain its passage, and he used an issue that had been debated in Congress for several years to further his cause. It was obvious that addressing all of the problems would require a multifaceted approach, and it happened that some of the tools were already available. The government had a complex of idle chemical plants and a hydroelectric dam at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, that had been built during World War I to produce nitrates needed to make explosives. The nitrates could be converted to make fertilizers for farmers, and the dam could produce electricity. Senator Norris felt strongly that the public rather than private companies should receive the benefits from the government's investments, and this argument was a key to gaining congressional approval.

TVA began by helping provide the tools for the region to restore its basic

natural resources, the water, the soil, and the forests. In less than a year

there were two construction projects under way to build dams to harness the

region's vast water resources and put them to work, and to provide flood control.

New fertilizers were developed, and state agricultural extension services were

enlisted to teach farmers how to use their land to grow more crops and protect

it from erosion. Forests were replanted, and wildlife and fish populations

were improved.

The most dramatic impact on the people came from electricity generated by the TVA dams. Electric lights and modern appliances such as electric stoves, refrigerators, and washing machines made life easier and more productive. The abundance of inexpensive electricity also drew industries into the area and provided desperately needed jobs.

The gates on the first TVA dam, named for Senator Norris, were closed in 1936, and the revitalization of the valley was well under way. Great progress was being made; then only a little more than four years after Norris Dam began operation, World War II broke out. TVA was faced with another challenge: producing the immense amounts of electricity the aluminum plants needed to produce aluminum for airplanes, as well as electricity for the top-secret Oak Ridge project. New records were set in building new dams. Between 1941 and 1945, five major dams were completed, and a 650-mile, year-round navigational channel on the Tennessee River from Knoxville, Tennessee, to Paducah, Kentucky, was created.

In total, from 1936 to 1977, 15 dams were constructed in the region, and in addition to the original purposes, the impoundments had other benefits. Fishing, boating, picnicking, camping, and swimming became family pastimes, and early on TVA began developing lakeside parks and recreational areas to meet these recreational needs.

In the 1950s as the demand for electricity was outstripping the capacity of its hydroelectric units, TVA began a 20-year process of building coal-fired electric plants. By 1973 these steam plants accounted for three-fourths of TVA's generating capacity. They also created controversies over the strip-mining of coal and the pollution resulting from the burning of coal in the power-generating plants. Law suits led TVA to work out an agreement to clean up the air around these plants.

TVA entered the nuclear era in 1966 when estimates showed that a nuclear plant

could produce electricity cheaper than a coal plant. The first project, the

Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant, the largest in the nation, went into operation

in 1974. In addition, work was begun on six other plants, but as energy needs

changed due to soaring costs, construction was stopped on three of the plants

in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

A huge controversy erupted in 1967 when TVA began work on the Tellico Dam project on the Little Tennessee River. Conservationists and environmentalists claimed that the project couldn't be justified on the basis of flood control, power production, navigation, recreation, or industrial development. Dam opponents were supported not only by independent studies but also by TVA's own statistics. Regardless, the dam was built, and TVA's image was badly marred.

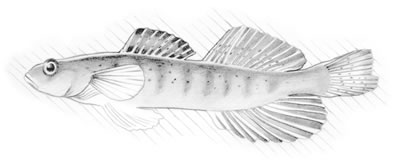

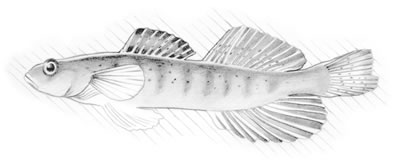

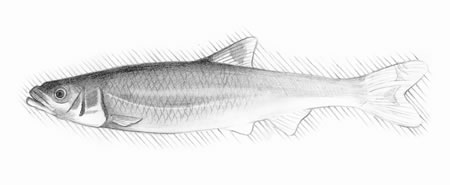

At the heart of the controversy was a small fish not found anywhere else in the world. The snail darter (Percina squamata) became the rallying cry for environmentalist. The snail darter was on the national endangered species list, but Congress voted to wipe out this species with the blessings of the Supreme Court. This act became a lightning rod, attracting the ire of the environmentalists. The environmentalists eventually lost to TVA and Congress, and the dam was built.

This all took place before the small fish was located in other streams in 1973. Today the fish lives in many tributaries of the Tennessee River in Tennessee and in one in Alabama. The Snail Darter Recovery Team recommended the darter be reclassified as a threatened species. This was done in 1984.

Over the years TVA gained control of power production at all of the dams in the Tennessee River drainage system, some of which are outside the state's borders. This allows the agency to coordinate the flow of electricity throughout the system and maintain suitable levels under all circumstances.

Despite some bumps in the road, TVA has adjusted to present realities and remains a vital force with a variety of new projects under way. Electric cars and experimental batteries are being tested in Chattanooga, and agricultural and forestry scientists are studying ways to turn farm products and wood into alcohol for fuel. A pilot plant is now experimenting with methods for burning coal more efficiently and cleanly. Partnerships programs with local communities are turning urban waste into new fuel and fertilizer sources. Solar water heaters and other conservation technologies have been placed in valley homes. The agency also operates one of the nation's foremost training centers for nuclear plant personnel.

For more information: A map of the TVA lake system and a listing of all of the commercial resorts, campgrounds, and marinas can be obtained from Communications/Public Relations, TVA, 400 West Summit Hill Drive, Knoxville, TN 37902-1499. Phone (423) 632-6263.