The

Beech Creek–Chimney Rock Loop

The

Beech Creek–Chimney Rock Loop

If one had to select a national park site in Georgia, this land of gorges, waterfalls, and scenic splendor would be it. Hunters of bear and hog have used the area for years. Only now are horseback riders and hikers discovering this watershed and its myriad trails, many of them connecting with the Appalachian Trail. There was no easy way for the early settlers to reach the remote valley called Tate City, a pastoral setting rimmed by a great northward flex of the Blue Ridge. Tate City was once a busy corundum mining community and later a logging town with stores and churches. Now only two churches and a handful of homes remain. Most of the original mountain people who lived by subsistence agriculture are gone. The bears and perhaps even the cougar have returned.

[FS 70 to Fig. 35(17)] This drive up the Tallulah's upper gorge is spectacular. It begins at the bridge over the Coleman River. At this bridge is the trailhead for an exciting, short (less than a mile) trail up the gorge of the Coleman River through the Coleman River Scenic Area [Fig. 35(44)], described on a sign just north of the bridge. FS 70 dead-ends in the heart of the Southern Nantahala Wilderness. The major access point for the Tallulah River basin, FS 70 follows beside the Tallulah through the 3-mile-long Rock Mountain Gorge [Fig. 35(43, 41)], on the old railroad bed, which was blasted out of solid rock by the lumber company logging the valley in virgin timber days. This lovely road crosses the Tallulah four times. The picturesque gorge has been the site of television commercials and postcard vistas. One can picnic on the rocks or fish the pools stocked weekly with eating-size rainbow trout. In the gorge grow a number of the beautiful and rare flowering tree, the mountain camellia, or Stewartia, which blooms in June and July. The best place to see the tree is in a stand at a wide place in the road at the extreme southern end of the Tate Branch Campground [Fig. 35(39)]. At Line Branch, one can look back, high up at the Flat Branch Falls [Fig. 35(42)]. Just below the Tate Branch Campground, Charlie's Creek Road fords the river. When this road emerges on a flat near the AT, a north-turning fork [Fig. 35(36)] leads one to the main Charlie's Creek. Across the creek and up the road a few hundred yards, there is a trail up to an amethyst mine [Fig. 35(34)] that has produced some of the finest gem amethysts in the United States.

The

Beech Creek–Chimney Rock Loop

The

Beech Creek–Chimney Rock Loop [Fig. 35(28)] This 12-mile loop hike has been a favorite of scout groups for many years. Skirting private property, the lower trailhead is at the "Glory Patch" [Fig. 35(28)] and crosses a low gap in Scaly Ridge before descending to the Beech Creek log road trail at an old homesite. Shortly thereafter, this main road crosses Bull Cove Branch. A striking cliff and falls with rich herb growth lies just out of sight upstream [Fig. 35(26)]. The road then fords Beech Creek [Fig. 35(25)] to enter the stunningly beautiful Beech Creek Gorge [Fig. 35(23)] (a trail to the left [Fig. 35(24)] leads to Bear Gap). In about 2 miles, the log road trail reaches an old ore-crusher foundation of packed rock [Fig. 35(22)] and begins switchbacks up through the vast cliffs [Fig. 35(19)] on the face of Big Scaly Mountain. At about the second switchback left, a prominent trail goes off east and down to the creek, where it reaches beautiful High Falls [Fig. 35(21)], probably 200 feet high. Trail length is less than .25 mile.

The old Tate corundum mine is high in the cliffs [Fig. 35(20)], and the remains of the old oxen haul road (made of dead-packed, or mortarless, rock) up to the mine may be found to the left (west) at about the third switchback to the east. If one goes west through the cliffs, there are perhaps 50 acres of virgin slope forest. It is possible to hike through this to Chimney Rock. Bears raise and den in these cliffs [Fig. 35(19)] and are often seen in the gorge below if the visitor can remain quiet. After gaining the "top" of the cliffs on the main road, one enters an incredibly long "flat" [Fig. 35(13)]. After 1.5 miles arrive at the Beech Creek Spring [Fig. 35(8)], once the site of an Adirondack shelter. Approaching the spring on the left, pass through an unusual climax variety of northern hardwood forest of beech with yellow birch and hop hornbeam [Fig. 35(11)]. This is possibly a relict Ice-Age forest of the Pleistocene era, 15,000 to 20,000 years ago.

At this point, the hiker is about 4,600 feet above sea level. Upslope, at about 4,700 feet, enter a totally different environment—a high-altitude or northern oak ridge forest which can best be experienced on the trail [Fig. 35(12)] to the top of Big Scaly. Near Beech Creek Spring, the forest of rich black soil was once principally northern red oaks. Trees were wide apart, and the area resembled an orchard. Trunks were short and limby. One can find a few of these ancient specimens missed by loggers. There are numerous small chestnut sprouts. Fraser firs are also here, planted, as they are on top of Standing Indian [Fig. 35(1)]. The Beech Creek Flat [Fig. 35(13)] is a mecca for wildflower lovers. The highly prized ramps, or "mountain garlic," grow in profusion and are found near to Bear Creek Falls in the gorge below.

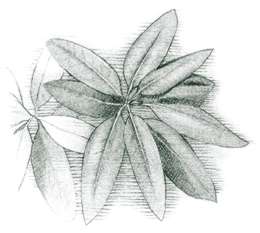

Just north of the spring is an area of naked red earth, clay-rich soil that deer eat. This is the "Indian Stomp Ground" [Fig. 35(7)]. It is certainly possible that the Indians danced here, but early settlers may have invented this name as an explanation for the naked ground. Several hundred yards beyond, a log road turns left. Here, a gentle nature trail [Fig. 35(12)] leads through virgin northern red oak ridge forest to the rocky summit of Big Scaly (5,200 feet), surrounded by dense purple rhododendron and yielding magnificent vistas to the northwest and southwest.

One

can take the very steep and poorly marked Appalachian Trail connector trail

[Fig. 35(6)] to the

AT, where one will find areas of shrub bald [Fig.

35(4)]. To the left (north) is Standing Indian Mountain (5,499 feet)

[Fig. 35(1)]. To the

right (south) is Little Bald (5,015 feet) [Fig.

35(29)], which one can also reach from the loop trail [Fig.

35(28)]. Just south of Little Bald is Dick's Knob [Fig.

35(32)], the third highest peak in Georgia. Just before Case Knife Gap,

a few feet past the turnoffs of the Big Scaly and AT connector trails, the

north-facing cove to the right has a boulderfield [Fig.

35(3)] with some northern hardwoods. Go down past a spring and follow

the small branch.

One

can take the very steep and poorly marked Appalachian Trail connector trail

[Fig. 35(6)] to the

AT, where one will find areas of shrub bald [Fig.

35(4)]. To the left (north) is Standing Indian Mountain (5,499 feet)

[Fig. 35(1)]. To the

right (south) is Little Bald (5,015 feet) [Fig.

35(29)], which one can also reach from the loop trail [Fig.

35(28)]. Just south of Little Bald is Dick's Knob [Fig.

35(32)], the third highest peak in Georgia. Just before Case Knife Gap,

a few feet past the turnoffs of the Big Scaly and AT connector trails, the

north-facing cove to the right has a boulderfield [Fig.

35(3)] with some northern hardwoods. Go down past a spring and follow

the small branch.

Down the loop road and through Case Knife Gap is the Chimney Rock watershed. This section is not nearly as steep as the Beech Creek section. Descending, watch carefully the ridgeline that comes down westerly from Big Scaly. Sticking slightly above it will be Chimney Rock [Fig. 35(18)]—a climbable (with great care) rock formation that affords a tremendous view of the watershed and is reached by a short (less than .25 mile), indistinct trail winding up through huge, scenic rocks. The trail turns south in a flat about 200 yards below the last fork of Chimney Rock Branch that is forded. The main log road trail continues down, passing through a gap [Fig. 35(16)] overlooking the Waterspout watershed and then meeting the Deep Gap Trail in an old pasture now full of saplings. The Girl Scouts's primitive camping area was located here [Fig. 35(10)]. A trail leads to Thomas Falls from the Deep Gap Trail [Fig. 35(9)], and New Falls [Fig. 35(40)] is at the bluff where Wateroak Creek leaves Collary Cove.

Many of the streams entering the Tate City Valley have waterfalls.

DENTON CREEK FALLS. [Fig. 35(31)] A sheer drop easily reached about .25 mile upstream from the first ford (where the road is blocked). See Fig. 35.

FALL BRANCH FALLS. [Fig. 35(33)] Best visited from the top by way of the Bly Gap Trail [Fig. 35(30)], a long trail which at Bly Gap [Fig. 35(27)] intersects both the Appalachian Trail and a road down into the Shooting Creek Valley. Park at the trailhead.

[Fig. 35(17)] This trail offers a number of smaller falls. Generally moderate, it is difficult in one place. Halfway up, a logging road intercepts the trail, making the rest of the climb easy and providing a view of Chimney Rocks [Fig. 35(15)], the formidable Brush Mountain Cliff [Fig. 35(14)], and rhododendron slicks. It proceeds to intersect both the AT and the Chunky Gal Trail at White Oak Stamp [Fig. 35(5)].

This road provides access to the wilderness and to the Coleman River headwaters.

[Fig. 35(44)] This picturesque 330 acres encompassing the lower Coleman River was dedicated in 1960 to "Ranger Nick" Nicholson following his 40 years of public service. A 1-mile-long trail passes up the gorge with its pools, cascades, and shoals. Some large examples of evergreen trees, especially hemlock, can be seen. Fraser magnolia is common and Stewartia occurs. Carolina rhododendron is unusually abundant. Between the Tallulah Campground and the Scenic Area trailhead is a mini-gorge containing the "strainer hole" [Fig. 35(45)] which, prior to dynamiting, had a hydraulic, or "keeper," at its input which drowned several people.

[Fig. 36, Fig. 38(1)] At 600 feet in depth, Tallulah Gorge is one of the deepest and most spectacular gorges in the East. It is geologically unique, being cut down in resistant quartzite, quite unlike the gneisses and schists of the surrounding mountains. It is a textbook example of stream capture. Originally, both the Chattooga and Tallulah rivers were headwaters of the Chattahoochee River. The Savannah River, down-cutting more rapidly, eventually cut back and robbed the Chattahoochee of these two streams. Over millions of years, the river has carved out the gorge.

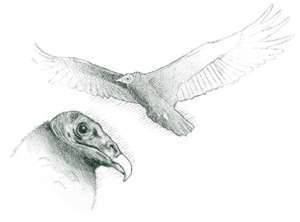

The rare, persistent trillium and a wealth of other flora are found in the gorge. So is the green salamander, a rare crevice-dweller. The bird density is low, consisting mainly of vultures, phoebes, and swallows. Both the rare Carolina hemlock and table mountain pine grow around the gorge rim. Carolina rhododendron is unusually abundant. This is one of the few areas where the rare fringed polygala may be found.

Until the turn of the nineteenth century, Tallulah Falls and Tallulah Gorge were relatively unchanged by man. For centuries, only the Cherokee Indians inhabited the area, and few whites penetrated the wilderness. The few white hunters and traders who wandered through the area told stories about the gorge and its mysterious thundering waters. Even the Cherokees seldom ventured into the gorge, believing it to be inhabited by a strange race of "little people" who were alleged to live in the nooks and crannies of the cliffs overlooking the falls. The Cherokees also believed that one of the caves in the gorge was the entrance to the "Happy Hunting Grounds"; if an Indian ever entered, he would never return.

After the Cherokees were driven out in 1819, white adventurers began to explore the region. Within a year of the Cherokees' departure, spectacular accounts were circulated concerning this natural wonder in the northeast Georgia mountains. Although great stamina was required to make the trip, tourists began forging their way through the mountains to see this curiosity of nature. Clarkesville was the closest point where pack horses could be obtained to begin the 12-mile trek through the mountains to the gorge.

Interest in Tallulah Falls and Gorge had spread beyond Georgia. During the 1830s and 1840s, foreign and American dignitaries began to make pilgrimages to the region. The area's attraction is not hard to understand. The gorge itself is a 3-mile-long gash in the earth that reaches a depth of almost 600 feet, bordered by rocky, vertical walls. The Tallulah River carries runoff from a watershed area of over 200 square miles. In those days, this mighty river roared into the gorge over a series of spectacular cataracts, creating a continuous, thundering sound that echoed through the gorge day and night.

At

the head of the gorge, the bed of the Tallulah River suddenly became narrow,

creating a swift current headed toward the first falls. Tourists named this

narrow bed Indian Arrow Rapids. The first of the great falls over which the

Tallulah poured into the gorge was named Ladore; then came the 76-foot-high

Tempesta Falls; then, the 96-foot Hurricane Falls. The fourth of the great falls

was named Oseana. Next was Bridal Veil Falls, with a drop of 17 feet. And last

was Sweet Sixteen Falls, with a 16-foot fall. Beyond the falls, deep in the

canyon, was a great bend in the river called Horseshoe Bend, from which visitors

liked to gaze upward to guess the height of the towering cliffs. Many streams

and creeks poured over the canyon rim into the gorge below and were given appropriate

names—no one knows exactly by whom. The pool at the bottom of Ladore Falls

was named Hawthorne Pool, in memory of a man who fell to his death there. A

natural water slide on the side of the gorge was named Hank's Sliding Place,

in memory of a native of the region who slipped and fell more than 100 feet

into the raging river below and lived to tell about it. The thundering waters

beneath an overhanging rock reminded someone of the voice of Satan, so that

rock was named Devil's Pulpit—probably the most popular tourist site at

the gorge, then and now. An outcropping that reminded someone of a profile was

given the name Witch's Head and was a popular spot for photographers in the

nineteenth century.

At

the head of the gorge, the bed of the Tallulah River suddenly became narrow,

creating a swift current headed toward the first falls. Tourists named this

narrow bed Indian Arrow Rapids. The first of the great falls over which the

Tallulah poured into the gorge was named Ladore; then came the 76-foot-high

Tempesta Falls; then, the 96-foot Hurricane Falls. The fourth of the great falls

was named Oseana. Next was Bridal Veil Falls, with a drop of 17 feet. And last

was Sweet Sixteen Falls, with a 16-foot fall. Beyond the falls, deep in the

canyon, was a great bend in the river called Horseshoe Bend, from which visitors

liked to gaze upward to guess the height of the towering cliffs. Many streams

and creeks poured over the canyon rim into the gorge below and were given appropriate

names—no one knows exactly by whom. The pool at the bottom of Ladore Falls

was named Hawthorne Pool, in memory of a man who fell to his death there. A

natural water slide on the side of the gorge was named Hank's Sliding Place,

in memory of a native of the region who slipped and fell more than 100 feet

into the raging river below and lived to tell about it. The thundering waters

beneath an overhanging rock reminded someone of the voice of Satan, so that

rock was named Devil's Pulpit—probably the most popular tourist site at

the gorge, then and now. An outcropping that reminded someone of a profile was

given the name Witch's Head and was a popular spot for photographers in the

nineteenth century.

As tourists grew impatient with making the long trek from Clarkesville and with having to camp at the gorge, inns sprang up near the attraction. Fine hotels were built, able to accommodate as many as 300 guests. Tallulah Gorge became a mecca for summer vacationers, offering cool temperatures, great views, and accommodations for rich and poor.

The old Tallulah Falls Railroad, which reached the gorge in 1882, ran along its western rim. The cuts may still be seen, and the old train station at Tallulah Falls Dam is now a craft store. This railroad, which ran from Cornelia to Franklin, was the principal means of bringing visitors to the gorge in the early years. Before the right-of-way was sold in the 1950s and the many wooden trestles were demolished, it was the setting for Walt Disney's film The Great Locomotive Chase.

On July 24, 1886, a crowd estimated at 3,500 to 6,000 people assembled to watch Professor Leon walk across the gorge on a tightrope. His historic feat began on the north rim at Inspiration Point, the highest point in the gorge at 1,200 feet. When he was near the center, one of his guy lines broke and the professor fell. Luckily, he caught the cable and sat on it for 25 minutes, before completing his walk.

In 1905, the state legislature made an effort to buy and preserve the land around Tallulah Gorge, but could not raise the $100,000 needed to make the purchase. Three years later, what was to become Georgia Power Company was organized by E. Elmer Smith of York, Pennsylvania, and Eugene Ashley of Glens Falls, New York. In 1909, these two men obtained the $108,960 necessary to purchase the strategic tract of land around the head of the gorge.

Efforts were made to rescue the Tallulah River and Gorge from development. In the first large environmental battle in the state's history, a group of citizens led by the widow of Confederate general James Longstreet appealed to officials of Rabun County, to the state legislature, to the governor, to the Georgia Supreme Court, and even to President Taft. But it was too late. Work on Tallulah Dam began.

Throngs

of people came to the gorge area to watch this remarkable engineering feat.

But more came in 1912 to view Tallulah Falls for the last time.

Throngs

of people came to the gorge area to watch this remarkable engineering feat.

But more came in 1912 to view Tallulah Falls for the last time.

From its mile-high beginnings on the southwest slopes of Standing Indian Mountain in North Carolina, the Tallulah had bounded southward through the north Georgia mountains for centuries, falling more than 4,700 feet during the 46-mile journey to its confluence with the Chattooga beyond the end of Tallulah Gorge, at the South Carolina border. Its last 4 miles, beginning at the falls, had been the most dramatic. Over these falls the river had plunged downward a total of 600 feet in less than 1 mile.

In September of 1913, with the dam at the head of the gorge completed and the river diverted through its powerhouses, electricity flowed for the first time over the wires to Atlanta—to run the city's trolley cars. The "terrible" Tallulah River, as the Cherokees had called it, had been tamed and reduced to a trickle, dripping through Tallulah Gorge.

The decline of Tallulah Gorge as a tourist attraction was rapid thereafter. Many hotels closed. Others were burned in a fire of 1922 that almost destroyed the little tourist town of Tallulah Falls. Two years later, the construction of US 441 bypassed the town of Tallulah Falls altogether.

The moaning of the wind is the only sound that comes from the gorge now, although the place has enjoyed a few brief moments of notoriety. On July 18, 1970, Karl Wallenda duplicated Professor Leon's tightrope walk across the gorge, completing the distance in under forty minutes and breaking the professor's record for speed, if not for distance. In 1972, scenes for the movie Deliverance were shot in the canyon.

Today, almost a century after the first unsuccessful effort to turn the gorge into a state park, a unique partnership between the state of Georgia and the Georgia Power Company has done just that (see Tallulah Gorge State Park, below). Hiking trails, scenic overlooks, and an interpretive center will help lure tourists back to this remarkable area. As part of the park development plan, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, in conjunction with state and national environmental organizations and the Georgia Power Company, has come up with a plan for water releases from Tallulah Dam, which addresses a wide range of practical, recreational, and scenic considerations.

While the details of this plan may change due to practical experience, it presently allows for a continuous water flow of 35 cubic feet per second (CFS) into the gorge. This slight volume of water is similar to the 12 CFS that flows through the gorge now and allows hikers to explore the bottom of the gorge. On 14 weekends per year during daylight hours, the flow will be increased to 200 CFS, or what's termed as "aesthetic flow." (As this book goes to press, aesthetic flows of 200 CFS are scheduled to occur every weekends: the third weekend in April–Memorial Day weekend, Labor Day weekend–the last weekend in October. "Aesthetic flow" raises the water in the gorge to approximate pre-dam levels and allows visitors to witness the scenic beauty of the waterfalls as well as the whitewater flowing through the rest of the gorge. Hikers may be prohibited from entering the gorge when water is at the 200 CFS level.

On five weekends per year (now scheduled for the first two weekends in April and the first three weekends in November), the flow will be increased to between 500 and 700 CFS, significantly increasing the whitewater drama of the gorge. During these periods, a limited number of canoeists and kayakers may challenge the rapids of the 2-mile canyon. Hiking in the gorge is likely to be prohibited at the 500 CFS level. Call the state park for a current schedule of water releases, rules of access, and information about boating in the canyon.

Tallulah

Gorge State Park

Tallulah

Gorge State Park [Fig. 36] Tallulah Gorge, located in the historic town of Tallulah Falls, was designated a state park in 1992. The 3,000-acre state park is jointly operated by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the Georgia Power Company through a unique public-private partnership.

Six hiking trails are open to the public: North and South Rim Trails [Fig. 36(12,13)]; Sliding Rock and Hurricane Falls Trails [Fig. 36(21,11)] with gorge floor access (2.5 miles round-trip, very strenuous, permits required); multi-use Stoneplace Trail [Fig. 36(19)] for hiking, mountain biking and backcountry camping (5 miles one-way, moderate to difficult, permit required); Shortline Trail (3-mile paved trail following Old Tallulah Falls Railroad Bed for hiking and bicycling); and Terrora Trail [Fig. 36(1)] (1-mile loop, moderate). Detailed information and free, required permits available at the Interpretive Center.

Whitewater boating releases are scheduled for the first two weekends in April and the first three weekends in November, 8 a.m. – 4 p.m. Permits are required for the 120 kayaking spaces available each weekend and can be obtained through Tallulah Gorge State Park. Water volumes are 500 cfs (cubic feet per second) on Saturday and 700 cfs on Sunday. Kayakers access the river below Hurricane Falls and can be best viewed from North Rim Trail Overlook 1. Aesthetic water releases of 200 cfs are scheduled for several days during spring and fall. Call the park for exact dates.

Rock

Climbing in Tallulah Gorge

Rock

Climbing in Tallulah Gorge Tallulah Gorge contains a variety of popular rock-climbing sites for all skill levels. A strict permitting policy is in effect and only 20 permits per day are issued. No permits are issued during inclement weather and no advance reservations are taken. To apply for a permit, go to the Jane Hurt Yarn Interpretive Center on South Rock Mountain Road in the park (see Tallulah State Park directions).

The destinations below, whether reached by car, canoe, foot, or a combination thereof, provide a rare opportunity for visitors to view the mountains from scenic lakes, run the rapids of what remains of Tallulah Gorge, and pay tribute to what was once one of the mightiest rivers in Georgia. The guide that follows provides directions for canoeing 31.5 miles of the Tallulah River, including its scenic impounded lakes and sections of the river where Class I–IV rapids provide hints of what the river once was. The trip can be divided into six parts or done as one long trip. The driving directions to put-ins and take-outs provide an opportunity for visitors to see much of the same terrain by car.

THE FIRST 10 MILES. Although the first 10 miles of the Tallulah are uncanoeable, driving streamside is worthwhile for the mountain scenery alone. See directions for the Upper Tallulah Basin Drive.

THE UPPER TALLULAH—SECTION 1. This section begins 10 miles from the source of the river. It offers miles of Class I–III whitewater paddling on a relatively untouched area of the river beside the Coleman River Wildlife Management Area, and 2 miles of paddling on the backwaters of Lake Burton.

LAKE BURTON—SECTION II. Lake Burton, the largest of the five reservoir lakes on this trip, impounds almost 10 miles of the Tallulah River in its 2,775 acres. A many-fingered mountain lake with 62 miles of shoreline, Burton serves as a reservoir, controlling the water flow to Lakes Seed, Rabun, Tallulah, and Tugalo below. It is a favorite spot for fishermen. Impounded in 1919 upon completion of Burton Dam, it was named after the town of Burton, which once occupied the site on which the lake now stands. Lake Burton is a large, deep lake, and canoeists must be alert for rapidly rising winds and thunderstorms. Paddling near the banks is recommended. Follow the map carefully to avoid making a wrong turn into one of its dead-end fingers.

LAKE SEED—SECTION III. Lake Seed, sometimes called Lake Nacoochee, offers a canoeing experience entirely different from that offered by Lake Burton. Burton's wide and many-fingered layout provides breathtaking views of distant mountains. Seed, on the other hand, is tight and narrow and follows the original bed of the Tallulah River quite closely. Seed is 4.5 miles long, impounded by the 75-foot-high Nacoochee Dam, completed in 1926. The lake has a 13-mile shoreline. The canoe route goes 3.5 miles, from the put-in at the base of Burton Dam to the public boat ramp on Lake Seed. Georgia Power Company offers primitive campsites at Lake Seed on a first-come, first-served basis.

LAKE RABUN—SECTION IV. Lake Rabun has been a popular recreation area for many years. Houses and cottages were built on its shores as early as the 1930s, and today its 25-mile shoreline is dotted with homes. Georgia Power Company, which owns most of the shoreline and leases land for homes, limits development, so sprawling motel complexes are not present. This 8-mile trip is winding and scenic, offering a stop at the popular Rabun Beach Recreation Area located just off Lake Rabun Road. On the lake, stick close to shore to avoid heavy motorboat traffic. The Nacoochee Park Recreation Area offers picnic tables and restrooms.

TALLULAH RIVER AND LAKE TALLULAH—SECTION V. The special feature of this 5.5-mile stretch is that it follows for 4 miles the original bed of the Tallulah River, offering significant rapids, including a Class IV. The final 1.5 miles are on a lake complete with waterfalls and mountain streams trickling along its banks. This small lake, only 63 acres, is impounded by the 130-foot-tall Tallulah Dam. Completed in 1912, it was the first dam built on the Tallulah River. Its construction on the rim of Tallulah Gorge cut off most of the water for Tallulah Falls. Unlike its sister lakes, Lake Tallulah is full of yellow perch.

To scout the river, take the road that leads across the river to the Terrora Generating Station .8 mile from Terrora Park and to a bridge over the Tallulah River .9 mile beyond the park. These are good places from which to scout the four dangerous rapids in this section, one of them rated Class IV.

TALLULAH GORGE AND LAKE TUGALO—SECTION VI. The last 2 miles of canoeable water on the Tallulah River are in Tallulah Gorge, on the west finger of Lake Tugalo [Fig. 38(3)]. This section is canoed as a 4-mile round-trip, using the same point as put-in and take-out. The Tugaloo River begins where the Tallulah and Chattooga rivers meet, and its name, in Cherokee, means "fork of a stream." Lake Tugalo was formed with the completion of the Tugalo Dam [Fig. 38(5)] and Hydroelectric Plant on the Tugaloo River in 1922.

Lake Tugalo covers 597 acres and has 18 miles of shoreline. The property around the lake is undeveloped. Tugalo is surrounded by a mixed pine-and-hardwood forest that has been relatively undisturbed by logging because of its steep shoreline. Tugalo is a beautiful lake for both fisherman and canoeist. Catfish and bass fishing are good. Tugalo is one of the few lakes in Georgia where canoeing and slow boat traffic are the norm (boat motors are restricted to 10 HP or less). On a leisurely day's paddle around the lake, a canoeist can explore many spots accessible only by water. Paddling up the Tallulah River arm of the lake leads into the Tallulah Gorge; paddling on the eastern side leads into the Chattooga Gorge [Fig. 38(4), Fig. 47].

Waterfalls cascade into the lake at several points, and spring and summer wildflowers are abundant. Wildlife in the area include deer and turkey. There are plenty of places to stop along the shore to stretch, have a picnic, or explore. Fires and camping are allowed only in Tugalo Park.

The South Carolina side of the ramp [Fig. 38(3), Fig. 47(25)] is very steep and difficult to navigate with a big boat and trailer. The parking lot here is often full during rafting season, this being a popular take-out point for rafters completing Section IV of the Chattooga River. Tugalo Park [Fig. 38(6)] has primitive campsites level and big enough for a tent or small trailer. There is no reservation system.

The boat ramp in the park is level and graveled, giving access to the northern end of Lake Yonah.

For access from Georgia to Tugalo Park, turn east onto GA 15 Scenic Loop off US 23/441 south of Tallulah Falls. Turn south onto Tugalo Plant Road (the sign says "Georgia Power No. Ga. Hydro Group Hdqs. Office"). Go 3 miles, then turn left through a gate onto a gravel road (sign says "Tugalo Plant"). The park is approximately 2 miles ahead on a steep, winding, gravel road.

For directions and a U.S. Forest Service map of the Chattooga River Corridor (fee), stop at the Chattooga Whitewater Shop on US 76 in Long Creek.

Recreation

Areas and Hiking Trails

Recreation

Areas and Hiking Trails MOCCASIN CREEK STATE PARK. [Fig. 37(3)] This is a small park, 32 acres, built on a floodplain flat at the mouth of Moccasin Creek on the shore of Lake Burton. It is an excellent base of operations for area sight-seeing, hiking, and other recreational activities. Daily interpretive programs are offered June through August. Annual special events include the Lake Burton Fun Run, All About Mountain Trout, and Lake Burton Arts and Crafts Festival.

NON-GAME WILDLIFE TRAIL. [Fig. 37(4)] 1.2-mile loop trail. Along the way are grassy fields, areas of old field pines—that is, white, Virginia, and pitch pine—and old field scrub lacking a tree canopy. There is an extensive area of deciduous hardwoods with poplar, red oak, and occasional sycamore. In this community along Moccasin Creek, alders dominate the creek bank along with dog hobbles and some American holly. Yellowroot, a mountain medicinal herb, occurs along the stream.

HEMLOCK FALLS TRAIL. [Fig. 37(4)] This easy, 1-mile trail follows Moccasin Creek, a beautiful trout stream with cascades and a waterfall. A hardwood-rhododendron community with hemlock and white pine prevails along the creek. The canopy is mostly poplar, red oak, white pine, black birch, and hemlock. Fraser magnolia occurs. Hemlock Falls marks the end of the trail.

RABUN BEACH RECREATION AREA AND HIKING TRAIL. [Fig. 37(10)] Located amidst lovely mountain scenery of 934-acre Lake Rabun, the hiking trail starts from camping area number two on Joe Branch and goes .5 mile to Panther Falls and 1 mile to Angel Falls. From late spring until July, the trail travels through an outstanding display of flowering rhododendron.

MINNEHAHA TRAIL. This .2-mile trail follows Fall Branch until it dead-ends at 50-foot-high Minnehaha Falls.

Yonah

Lake

Yonah

Lake [Fig. 38] Lake Yonah, one of six lakes managed by Georgia Power Company, was formed when the Yonah Dam and Hydroelectric Plant was completed on the Tugaloo River between Georgia and South Carolina in 1925. Yonah, meaning "big black bear" in Cherokee, is immediately south of Lake Tugalo and covers 325 acres.

The land adjacent to the lake being very steep, there has been little timber harvested here. Happily, there remains an undisturbed heavy forest of pines and hardwoods. This area has a great diversity of plant life, including many wildflowers. Other than the common Georgia wildlife, including deer and turkey, there is an occasional bear. Private homes are built around the 9 miles of shoreline, leaving the only public access to the lake at the boat ramps. The Lake Yonah boat ramp is paved and level. There is a small dock. The parking lot will hold approximately 15 cars and trailers. A dumpster is provided for trash. There are no restroom facilities.

The lake is popular year-round for canoeing and fishing for catfish and bass and in the summer for water-skiing. Canoeists must use caution on the lake in warm weather because of the fast and constant ski traffic. The lake can be paddled easily in a day. A put-in spot to the right of the dam has many seasonal wildflowers and is good for picnicking.

Lake

Yonah Park

Lake

Yonah Park [Fig. 37(23), Fig. 38(11)] Located below the dam overlooking Tugaloo River. The river banks are steep and overgrown, making access to the river difficult.

[Fig. 37(21), Fig. 38(7)] Panther Creek originates on the southern slope of Stony Mountain at an elevation of 2,440 feet, meanders down 940 feet before crossing US 23 and 441 at the recreation area, and empties into the Tugaloo River, which forms the border between Georgia and South Carolina. According to scientists who have studied the area, the natural features of Panther Creek Gorge have changed little during the past million years.

The 6-mile Panther Creek Trail, marked with blue blazes, begins at the Panther Creek Recreation Area [Fig. 38(7)]. It winds through a forest of poplar, hemlock, white pine, oak, hickory, and red maple, with an occasional birch, as it follows the steep, rocky bluffs of the creek. The trees, some of which are over 100 feet tall, provide shade in the summer and a display of colorful foliage in the fall. There are many rock cliffs with mosses and ferns growing in the moist crevices. In early spring, trout lilies appear, followed by violets and trillium. Trailing arbutus, dwarf iris, and gay-wings grow low to the ground. Spring flowering shrubs along the trail include serviceberry and horse sugar. There are masses of mountain laurel blooming in May, and the white and pink blossoms of the rhododendron are present well into June. The flowers of the dogwood and silverbell trees add to the beauty of the spring display.

The creek itself drops in a series of cascades. Little Panther Creek enters Panther Creek .6 mile before the stream turns sharply east at Mill Shoals, a former mill site [Fig. 38(9)]. Approximately .5 mile farther, 3.6 miles from Panther Creek Recreation Area and 2.4 miles from the eastern end of the trail, the creek falls 60 to 70 feet into a pool [Fig. 38(10)]. The trail leads down to the pool where there is a grand view of the falling water. This waterfall is preceded by an impressive Mill Shoals Falls, which could be mistaken for the more dramatic falls farther on. The trail ends at a dirt road near the point where Davidson Creek joins Panther Creek. The road continues for 2 miles to Lake Yonah Dam and Park.

The

eastern, or lower, end of the trail is designated a Protected Botanical

Area by the U.S. Forest Service because of the richness and diversity of

its plant life. This area is unique because it is within the Brevard Fault

Zone. A relatively narrow band of limestone within the fault supports vegetation

not commonly found in north Georgia. The soil allows calcium-loving plants,

such as chinquapin oak, to thrive here. The herbs, in particular, are remarkable.

The

eastern, or lower, end of the trail is designated a Protected Botanical

Area by the U.S. Forest Service because of the richness and diversity of

its plant life. This area is unique because it is within the Brevard Fault

Zone. A relatively narrow band of limestone within the fault supports vegetation

not commonly found in north Georgia. The soil allows calcium-loving plants,

such as chinquapin oak, to thrive here. The herbs, in particular, are remarkable.

Overnight camping areas are limited, and water along the trail is not safe for drinking. The trail is moderately difficult to hike, with a few steep places. Hikers carrying heavy packs should be aware of the rocky overhangs and narrow trails.

Panther Creek, home to rainbow trout and redeye bass, is classified as a secondary trout stream. Fishing schedules are available on Georgia fishing licenses, which are renewable annually.