The Natural Georgia Series: The Chattahoochee River

|

The Natural Georgia Series: The Chattahoochee River |

|

Flowing

Through Time: The Chattahoochee Throughout History

Flowing

Through Time: The Chattahoochee Throughout History High in the Blue Ridge Mountains the ancient Chattahoochee River rises to begin its trek to the Gulf of Mexico. Beginning as a bold stream, its waters run cold and clear as it plummets to the Nacoochee Valley, and from there onto the Atlanta Plateau where it cuts a deep trench as it flows toward the Alabama line near West Point, Georgia. Today the river is dammed several times before it reaches Columbus, but once it ran headlong over boulders, throwing up suds of white water as it raced southward. A series of waterfalls mark the river's fall line where the Coastal Plain meets the fo othills of the Piedmont region. Before the Chattahoochee was dammed in modern times, these rapids were landmarks. Humans-red, white, and black-were attracted to "the Falls of Coweta" where white men would one day build Columbus at the head of river navigation.

South of the rapids the flatness of the terrain slows the Chattahoochee to a leisurely pace as it meanders southward between the states of Georgia and Alabama. At the southwestern corner of Georgia, the Flint River, which has shadowed the larger stream through much of its sojourn through Georgia, marries the Chattahoochee to form the Apalachicola River, a water body once described as having "the flavor of alligators, moccasins, and dank swamps, laced over with beards of Spanish moss." After about 500 adventurous miles, the longest river in the southeastern United States broadens into an estuary just north of Apalachicola, Florida, and then disappears into the Gulf of Mexico.

Since

the time of the mastodon, humankind has lived along the banks of the Chattahoochee.

The first Chattahoochee people erected large burial mounds near the river. The

huge Kolomoki complex, located on a tributary of the Chattahoochee near the

present-day town of Blakely, was built during the Woodland period (which lasted

from 1000 b.c. to a.d. 700). Kolomoki is one of the best known sites of these

ancient civilizations, dating to 1000 b.c. As many as 2,000 people lived at

Kolomoki.

Since

the time of the mastodon, humankind has lived along the banks of the Chattahoochee.

The first Chattahoochee people erected large burial mounds near the river. The

huge Kolomoki complex, located on a tributary of the Chattahoochee near the

present-day town of Blakely, was built during the Woodland period (which lasted

from 1000 b.c. to a.d. 700). Kolomoki is one of the best known sites of these

ancient civilizations, dating to 1000 b.c. As many as 2,000 people lived at

Kolomoki.

A later period of mound building known as the Mississippian period (which lasted from a.d. 700 to 1400) produced no less than 16 significant archaeological sites along the river-all of which are located from the fall line southward. The most important of these are the Cemochechobee site that once covered 150 acres in present-day Clay County, Georgia, and the Rood's Landing site in Stewart County, which was probably the capital of an extensive chiefdom that controlled all comings and going along the lower river.

Archaeologists are not certain what happened to the Rood's Landing and Cemochechobee people or to the other Mississippian peoples of the Chattahoochee. Most experts today agree that their civilization probably was decimated by European diseases for which they had little immunity. The settlement at Rood's Landing seems to have collapsed at about the time of Hernando de Soto in 1539.

As

fevers raged in the villages of the Chattahoochee River, the chiefdom that centered

on the Rood's Landing capital collapsed. Survivors from other areas moved into

the depopulated towns over the next couple of centuries. The diverse people

were often unrelated to each other and even spoke different languages, yet they

formed an alliance for mutual defense and friendship. Because speakers of the

Muskogean dialects dominated the confederacy, the Chattahoochee people were

known collectively as the Muskogee. White men later referred to them as Creeks,

probably because of their tendency to locate their towns on the banks of rivers

and their larger tributaries.

As

fevers raged in the villages of the Chattahoochee River, the chiefdom that centered

on the Rood's Landing capital collapsed. Survivors from other areas moved into

the depopulated towns over the next couple of centuries. The diverse people

were often unrelated to each other and even spoke different languages, yet they

formed an alliance for mutual defense and friendship. Because speakers of the

Muskogean dialects dominated the confederacy, the Chattahoochee people were

known collectively as the Muskogee. White men later referred to them as Creeks,

probably because of their tendency to locate their towns on the banks of rivers

and their larger tributaries.

The influence of this "Creek Confederation" extended from the Appalachian Mountains southward to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River. The twin towns of Coweta and Cusseta near the fall line formed its nucleus. Cusseta was situated on the eastern bank of the Chattahoochee a few miles south of modern day Columbus. Coweta was in today's Alabama, a few miles to the south of Cusseta, but its name was associated with the series of waterfalls and white water ending just north of Cusseta.

Water was a sacred element to the Creek Indians. At dawn every morning, summer and winter, every able-bodied man, woman, and child walked to the river and plunged under the water four times. After bathing, they returned home energized by having purged away the impurities of the preceding day. According to the Indians' way of seeing the universe, there were spirits in the waters, in the animals and plants, and in the rocks.

The Chattahoochee was more than a river to these people. The Indians believed that fantastic creatures swam in the waters and attracted prey with their charms. Besides being the habitat of magical serpents, the river was also home to fish that gave the Creeks sustenance in summer. During the spawning season, fish that swam upstream halted at the fall line, making the rapids of "Coweta Falls" one of the richest fishing sites in North America. In the summer when the water was at its lowest stage, the Indians gathered to spend the day catching fish. Using a rotenone-like chemical found in such plants as buckeye roots, they stunned the fish, then speared or clubbed the fish that floated to the surface. After a day's fishing, the roasted, baked, or fried fish served as the main course at a moonlight feast and dance.

The Indians also caught fish using gill nets, trotlines, baskets, and rock traps. At night they built fires in their canoes to attract the fish to them, then speared the fish or shot them with arrows as they swam toward the light. Their usual catch included bream, bass, catfish, drum, sturgeon, and shad.

Like the prehistoric Indians before them, the Creeks used the Chattahoochee as a highway. They devised portable leather boats to ferry across the river. These were made by cutting poles on site and stretching animal skins over them. When the Indians reached the other side, they threw away the poles, rolled up the leather, and took it with them to use the next time they needed a ferry. They made dugout canoes from elm, hickory, or cypress logs, often leaving the bark intact. When the Indians reached their destination, they simply dragged the dugout canoes up the bank and turned them over. Because the canoes resembled fallen logs, they could be easily concealed.

Part recreation site, part food source, part transportation artery, part spirit, the Chattahoochee was more important to Native Americans than modern man can ever appreciate. The Creeks may have named the river for the rocks along its banks, which they also held sacred. "Chat-to" may have meant "a stone;" "ho-che," "marked or flowered." Even though modern society has lost its collective memory of the sanctity of the river's waters, the Chattahoochee still bears the name of reverence that the natives bestowed on it centuries ago.

A

Land of Cotton

A

Land of Cotton To the white people who followed the Indians into the Chattahoochee River valley, the river symbolized wealth. Along this natural highway to the Gulf, they would clear their fields and send their cotton to market. The coastal port of Apalachicola at the river's end would one day be as familiar to British textile manufacturers as New Orleans or Savannah as a source of cotton.

By the spring of 1819, a few hundred Georgians had already settled illegally along the banks of the Chattahoochee. The white settlement of the valley increased exponentially as the Creeks released by successive treaties their lands south of Fort Gaines, Georgia, in 1814 and east of the Chattahoochee in 1825. A further impetus to settlement came when Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1821. When Georgians no longer found their river outlet to the Gulf blocked by a foreign power, there was nothing to hold back the onrush.

In the early nineteenth century, virtually all travel and commerce was dependent on rivers. Overland transportation amounted to following a narrow Indian trail through the wilderness. The public "roads" were merely slightly widened paths so narrow that two wagons could not pass each other without difficulty. Roads were used only to augment river travel by connecting one river system to another. Farmers used pole boats and rafts to carry the first cotton from Georgia downstream to Apalachicola Bay. At the coast the crafts were unloaded, and the boats were knocked apart and sold for their lumber. The crew usually walked home.

In the spring of 1822, the very first Apalachicola exports of cotton (266 bales) were loaded at the Apalachicola River's mouth aboard the William and Jane for New York. A United States customhouse was established at the mouth of the river the following year. In 1827 the Florida legislature formally established the settlement later known as Apalachicola and directed that wharves be erected and the harbor regulated. While the Floridians were busy with these developments, Georgia lawmakers encouraged white settlement of the former Indian lands lying between the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers by holding a free land lottery. Naturally, land lying along the rivers was the most prized, and the acreage where river navigation began on the Chattahoochee was so valuable it was not included in the giveaway. There at the ancient Coweta Falls, a city was planned that would become a commercial center. This strategic location would take advantage of the river that ran southward to the Gulf and of the falls capable of powering mills and factories. The lawmakers named this town Columbus.

Even though over 300 river miles separated Apalachicola and Columbus, they were joined symbiotically by the Chattahoochee. Clear passage between them was necessary for the very existence of each. As soon as the settlements were established, a pole boat named the Rob Roy moved up and down the river, taking down cotton and then, loaded with groceries, pushing its way back up against the current to Columbus. But the river's merchants needed a quicker and easier form of transportation.

The first to attempt to run a steamboat up the Chattahoochee from the bay was John Jenkins, one of the Florida trustees of the port of Apalachicola. His 89-foot boat Fanny began the journey in the spring of 1827. By cutting a 20-foot swath through a massive dam of fallen trees, he was able to proceed as far as Fort Gaines by the end of July. But there the Fanny had to wait for the winter rains before continuing upstream.

Nine days after the Fanny finally arrived at Coweta Falls, a second boat steamed up to the future site of Columbus just as a state-appointed surveyor was preparing to lay out the town. The boat captain took a group of local boosters on a pleasure excursion to court some business. However, the venture turned out to be a negative advertisement. On the return trip the boat could not make headway against the current, and many of the passengers got off and walked home.

Nevertheless, the rough little town of Columbus was soon booming. Realizing their dependence on the river, city leaders encouraged the state to improve the river for navigation. Columbus residents also planned to open navigation northward by pole boats. North of the Coweta Falls was a 20-mile stretch of treacherous rocks and falls, but once above them it was believed one could pass another 200 miles unimpeded. When the river was swollen, as during the winter months, many of the rapids were covered so that one traveling downstream could get within 4 miles of Columbus. As proof of this, one pole boat built in 1828 made at least two round trips to Gwinnett County (northeast of present-day Atlanta) to buy corn. Cotton from the upstream regions was the first to be sold in Columbus in the fall of 1828.

Most of the year, however, the falls acted as a great wall to separate the two ends of the Chattahoochee. Above Columbus, white settlers at the village of West Point, Georgia, traded with the Indians across the river and with other whites upstream. Colonel Reuben Thornton ran barges and flatboats from West Point to Standing Peachtree, about 60 miles upstream. Standing Peachtree, a fort on the site of an old Indian town located on the south bank of the Chattahoochee about 7 miles from present-day Atlanta's Five Points, became the nucleus of a small settlement. Thornton's boats delivered groceries mostly to the isolated settlements of north Georgia. Once, though, he set aboard a load of flour and pointed the bow downstream. The boat bucked wildly over the falls but made it all the way to Columbus. Once it arrived, there was no hope of returning by water. Instead, he probably sold his battered boats at Columbus and hired a wagon to transport his purchased sugar and coffee over trails to West Point, then built new boats to convey the groceries from there to Standing Peachtree. From there he wagoned the supplies yet farther to eastern Tennessee markets. Such was the nature of transportation in the 1830s.

Others ran flatboats between Franklin (north of Columbus) and West Point as early as 1838. But the river residents above the falls were more apt to ride their wagons overland to Savannah or Augusta for their supplies than to trek to Columbus. The various settlements in the present-day Atlanta area centered on taverns at ferries that allowed travelers to cross the river and continue on to Tennessee by land. Montgomery's Ferry was located near the fort at Standing Peachtree. Others were Pace's Ferry, Nelson's Ferry, and Johnson's Ferry. However, the majority of white settlers were more apt to cluster below the fall line where their egress to the Gulf was unimpeded.

Fort Gaines was one of the earliest settlements along the Chattahoochee. A fort here served as a refuge for whites living on both sides of the Chattahoochee as early as 1818. The town of West Point, Georgia was settled under another name in 1829. By 1831 it had an annual business estimated at between $40,000 and $50,000.

While commerce flourished on the eastern bank of the Chattahoochee, on the "Indian side" of the Chattahoochee, Creek Indian civilization was slowly disintegrating. The declining state of the once-proud Creeks attracted traders, whiskey sellers, and speculators. In search of food or whiskey to drown their woes, the generally harmless Indians wandered about in Columbus until dark, when they were required by law to return to the Alabama side of the river. Within the city limits the Indians usually posed no more than a nuisance to the white newcomers.

However, even the days of this meager way of life were numbered. In the year the town of Columbus was born, Andrew Jackson became president of the United States. Jackson intended to use his office to make the lives of those Indians still remaining in the East so uncomfortable that they would voluntarily emigrate west. As Alabama and the federal government turned the screws of law tighter, the Indians agreed to sign the Treaty of Cusseta in 1832. This last agreement signed by the Creek people living in the East ceded to the United States all unoccupied Creek lands east of the Mississippi River. The government encouraged individual Indians to sell out also, and each head of household soon found themselves at the mercy of a myriad of land speculators.

Meanwhile, the first bridge over the Chattahoochee ushered in still more white settlers. With every new farmer, tens of acres of timberland were cleared for growing cotton. The river no longer ran clear. Erosion washed the iron-rich soil into streams that fed the river, staining it red. By 1830 cotton exports from Apalachicola had soared to 5,000 bales. This level of commerce was exactly what was needed to sustain a healthy steamboat trade. Cotton and steamboats complemented each other; prosperity shone down like the sun on the farmers of the Chattahoochee.

Even though valley residents relied on the river for transportation, they learned to be patient with it. In the dry summer months the main stem of the river became shallow in many places. Every summer commerce slept. This inconvenience was forgiven, however, because the river usually rose again just as it was needed most. In the autumn as farmers ginned their newly picked cotton, the rains resumed to swell the river. By Christmas the river was usually full and frolicsome, ready and willing to shoulder the bounty of the autumn's harvest and deposit it at the coast. From there creaky ships set their sails to capture the ocean breeze loaded with Chattahoochee cotton.

Each fall the crude wagon roads that radiated out like spokes from the hub of each riverside community conducted wagons loaded with cotton from the surrounding fields. Columbus was the largest commercial center on the river. By 1845 the city had 200 businesses to serve the burgeoning wagon trade. Though primarily a cotton marketing center, Columbus also capitalized on its location at the fall line to become a major southern manufacturing center. Water-powered mills sprang up along the river. The first textile plant was running by 1838. Industry and commerce were also budding just north of Columbus along the fall line. In Troup County, cotton trading centers popped up along the river at West Point and Vernon. In 1850 the county boasted 10 flour mills, 11 sawmills, 14 gristmills, and four textile mills.

In addition to the major marketing centers, there were dozens of local markets along the river wherever one found a riverside warehouse and a steamboat landing. In the 1840s there were about 25 such establishments between Columbus and Apalachicola. In the lonely pine forests of the Chattahoochee Valley, these wharves served as gathering places. The sporadic arrival of a steamboat, announced by the blast of a whistle or the firing of a gun, brought people scurrying to the landing to watch the slaves load and unload the steamboat. Since many of these landings were located on steep bluffs, this process was quite interesting to observe and often perilous for the stevedores. Long wooden slides that extended from the top of the bluff to the river's edge conducted the cargo down the hill. Bale after bale of cotton, as well as other heavy freight (even pigs), was sent tumbling down the steep incline to be stored in the lower decks.

The river that ran alongside the plantations floating the cotton bales along to sea was challenged in the 1850s by a new form of transportation. Rail travel had many advantages over water travel. Generally rail travel was faster. Additionally, trains could travel on a schedule that was not dependent on the seasonal level of the river. Additionally, trains ran where rivers did not go.

Savannah was the driving force behind the Georgia railroad movement. With its location on the Atlantic Ocean, it offered a more direct route to market for west Georgia cotton than the Chattahoochee or Flint rivers, which took cargo to Apalachicola, then around the long Florida peninsula to its ultimate destination. The State of Georgia laid out a railroad to extend from Chattanooga, Tennessee to a point about 7 miles east of the Chattahoochee River. This "terminus" became Atlanta, a railroad town where three other rail lines joined the state's line by 1850. Savannah's city corporation sponsored the Central of Georgia line, which joined the state-owned Western and Atlantic line at Macon in 1843. From there Savannah badly wanted to tap the rich cotton lands lying between the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers.

For that purpose the city of Savannah, in conjunction with the Central of Georgia Company, organized the Southwestern line to tap both the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers. In 1853 the isolation of the Chattahoochee River valley was forever dissolved. A speaker at the jubilee that celebrated the occasion of the completion of the railroad from Savannah to the Chattahoochee emphasized the significance of the day when he said, "[Today] is the day that unites the waters of the Gulf with the Great Atlantic." Then the mayor of Columbus symbolically mixed a vial of water from the Chattahoochee River with one from the Atlantic Ocean.

The

Chattahoochee and the Civil War

The

Chattahoochee and the Civil War After the southern states seceded from the Union and the exhilaration of the first battles was replaced by more practical considerations, a worry hung like a foul odor over the river valley that first spring: an abiding fear that the enemy would capture Apalachicola and then follow the river northward through the cotton fields of Georgia and Alabama to the industrial center of Columbus. The fears of the valley residents were intensified when the Confederacy, lacking the men to guard the coast, abandoned Apalachicola in the spring of 1862. On the heels of the military evacuation, coastal residents frantically packed up their belongings and fled upriver. Most of the refugees went to Columbus on the Jackson and other steamers and stayed there throughout the war, but others set up camp in the river swamp for the duration of the war.

On April 2, 1862, the Union naval forces officially took possession of the

port of Apalachicola, allowing the natives remaining to keep their fishing boats

and to oyster and fish in the bay so long as they committed no hostile act.

Everyone upriver assumed it would be only a matter of time before federal gunboats

ascended the Chattahoochee. By the end of 1862, representatives of the river

counties of Georgia and Alabama had built gun emplacements into the river bluff

at Fort Gaines and other towns. They made plans to obstruct the river so that

the Yankee vessels could not penetrate the Chattahoochee. While residents thought

in terms of defense, Confederate

officials planned an offense. They organized to build gunboats at Columbus and

Saffold, Georgia, (in Early County) capable of breaking the enemy blockade of

the coast. Although it was assumed that the boats would be completed before

the river was obstructed, both projects proceeded without regard to the other.

In November 1862, the Confederate War Department created the long-awaited military district composed of the valleys of the Chattahoochee, Flint, Chipola, and Apalachicola rivers, with General Howell Cobb in command. With Cobb's appointment the many defense projects along the river finally were coordinated. He dispatched an engineer to survey the entire river system to determine the best site for obstructing the river and building batteries to defend those impediments. The primary site selected was at the Narrows, a point in the Apalachicola River near the confluence of the Chipola River.

Cobb also tried to raise an army large enough to effectively man the batteries and the roads leading to the river. He estimated he would need 5,000, but the Confederacy could not spare more than a few hundred men from the front.

As

the obstructions were being placed in the river at the Narrows, shipbuilders

were putting the finishing touches on the imposing CSS Chattahoochee,

a three-masted schooner about 130 feet in length. Many of the 120 crewmembers

had previously served on the Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimack)

when it battled the USS Monitor in the first duel between ironclads.

Duty on the Chattahoochee would not be so illustrious. Loyal to his first

priority of defending the river, Cobb decided he could not wait for the ship

to be finished before he ordered the chains to be drawn across the waters. Still

the ship's crew hoped that when they were ready, the obstructions could be broached

and they still could get out to sea.

As

the obstructions were being placed in the river at the Narrows, shipbuilders

were putting the finishing touches on the imposing CSS Chattahoochee,

a three-masted schooner about 130 feet in length. Many of the 120 crewmembers

had previously served on the Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimack)

when it battled the USS Monitor in the first duel between ironclads.

Duty on the Chattahoochee would not be so illustrious. Loyal to his first

priority of defending the river, Cobb decided he could not wait for the ship

to be finished before he ordered the chains to be drawn across the waters. Still

the ship's crew hoped that when they were ready, the obstructions could be broached

and they still could get out to sea.

But good luck never ran with the Chattahoochee. On its maiden voyage, the engine failed and the ship struck a rock, tearing a hole in the hull. A crewmember complained, "So the fate of the Chattahoochee has been decided on and the officers and crew will share the same ignominious fate. Laying here in the river to be prostrated by chills and fevers in the Spring and Summer."

As repairs were begun, the days dragged on, and the number on board the Chattahoochee diminished from deaths and desertions. The captain himself was soon ordered to Texas. "What is to become of the 'Chatt' and her crew?" wrote another officer of the ship. "We are certainly to leave the river." However, a few months later in June 1863, the ship's steam boiler exploded, killing 19 crewmen and dashing any remaining hopes that the vessel could serve the Confederacy.

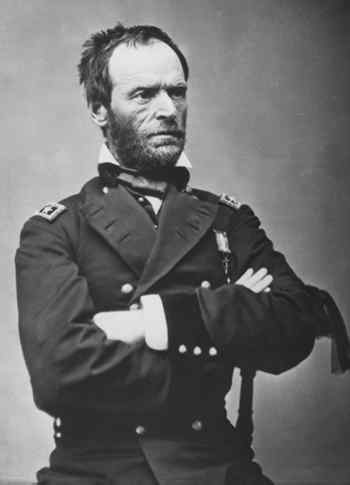

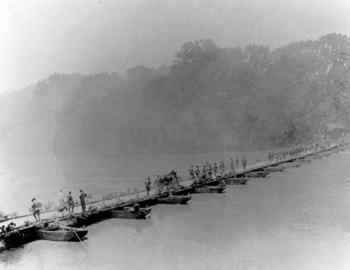

Ironically, when the enemy finally arrived, he came overland from the north and west instead of by way of the river. Atlanta turned out to be of even more strategic importance than the industrial center of Columbus because of the former city's rail hub. By taking Atlanta and controlling the railroad, the Union would cut the Confederacy in two. General William Tecumseh Sherman, who by 1864 commanded the Union forces of the Western Theater, set his sites on destroying the vital supply linkages needed by the Confederacy. With greater manpower than his adversary, he was able to flank the Confederates who had no choice but to retreat by degrees to the northwestern bank of the Chattahoochee. Then in a crucial maneuver that surprised the southerners, Sherman's army crossed the Chattahoochee and laid siege to the city. After several bloody battles, Atlanta surrendered on September 2, 1864 in total chaos.

Civilians fled Atlanta and its nearby towns for the relative safety of Columbus and Macon. Confederate casualties filled makeshift Columbus hospitals to overflowing. Food and supplies became scarce. Inflation was out of control. Chickens cost $4 to $5 each, and butter was $5 to $6 per pound. High unemployment made prices seem even higher. Even though Sherman marched to Savannah in November 1864, Columbus was not to be spared attack from the Union army.

In spring of 1865, from Alabama, Union cavalry commander General James H. Wilson divided his eastbound soldiers into two wings. One drove toward West Point, where the soldiers cut the railroad lines and destroyed supplies. The other, larger force headed for the factories of Columbus, which Wilson called the "key to Georgia."

On the Alabama side of the Chattahoochee River, Columbus factory workers, young boys, and old men waited nervously for the enemy, but in the darkness of that Easter Sunday night, the Federals slipped past them. The next day the invaders destroyed every industrial facility except the three gristmills. They set afire the cotton warehouses. They torched the ironclad Muscogee, only two weeks away from completion. Ironically, the destruction of Columbus was unnecessary, as the war had essentially ended seven days earlier at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia when Lee surrendered to Grant.

The Chattahoochee River had suffered as much as the people during the war. River captains found the river silted up and choked with wreckage in 1865. But as the people rebounded, so would the waterway. While the river was never again as central to the valley as it had been before the railroads came, the next era would be its last hurrah. The golden days of steamboating still lay ahead.

The

Golden Years

The

Golden Years The postwar steamboat era displayed more sophistication than the antebellum period had. New, opulent thoroughbreds replaced the more practical workhorses of the antebellum period. Individuals and companies owned lines of boats instead of only one boat. Innovations in service made river travel more reliable, and technological breakthroughs made it safer. Freight became more diversified with lumber products, fertilizer, and honey crowding the ubiquitous cotton bales.

The Naiad was probably the best-known steamer that ever plied the river, since it held the record for the longest continuous service on the Chattahoochee. Its dining room was set on the upper deck. Waiters moved noiselessly among the tables in starched white uniforms. Boat cooks were renowned for the flavor and abundance of their fare. On the down run there were "plenty of hot biscuits, hot cakes, meats, vegetables, pastries and the like." Returning from Apalachicola, plates brimmed with fresh shrimp, oysters, and fish.

By 1900 the nature of steamboat service changed noticeably. Instead of calling on every homestead or business, boats stopped at only 28 major communities or railroad junctions. And 16 years later, the steamers made only five stops. The river's natural character of drying up to a rivulet in the region north of Eufaula during periods of low rainfall was exacerbated by settlement of more lands along its banks. As farmers and developers loosed the red clay by forest clearing and field plowing, wind and rain swept the dirt into the riverbed. Silt filled the channel, and dredging operations were never thorough enough to remedy the situation. After 1900 the river trade shifted to the lower river, where navigation was not so difficult.

As water transportation became less reliable, its competition improved. By 1916 rail lines crossed over the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers in eight places below Columbus. At Columbus five different rail lines radiated from the city, and three railroads crossed the upper river between Columbus and the railroad hub of Atlanta. To make matters worse for the future of river travel, rails now ran in the same direction as the river instead of perpendicularly. When the railroad competed directly with the river, rail's more dependable and direct routes were sure to win.

In

addition to the railroad, the river had to compete with improved roads. By World

War I the automobile had become affordable to most Americans. New car owners

pushed for better roads. Paved roads encouraged a nascent trucking industry,

which also challenged river travel. In 1923 the John W. Callahan, the

last of the old-time paddle wheelers, struck a snag and sank in the lower river.

Only one more passenger steamboat would ever paddle up and down the Chattahoochee.

The George W. Miller ran excursions during the 1940s but its career ended

with World War II.

In

addition to the railroad, the river had to compete with improved roads. By World

War I the automobile had become affordable to most Americans. New car owners

pushed for better roads. Paved roads encouraged a nascent trucking industry,

which also challenged river travel. In 1923 the John W. Callahan, the

last of the old-time paddle wheelers, struck a snag and sank in the lower river.

Only one more passenger steamboat would ever paddle up and down the Chattahoochee.

The George W. Miller ran excursions during the 1940s but its career ended

with World War II.

The public would never again know the Chattahoochee as intimately as it had during the age of the steamboat. Yet the river was far from forgotten when the old paddle wheelers disappeared. In the ensuing years, reliance on the river would actually increase as people came to depend on hydroelectric power to light both the cities and the countryside and to turn the wheels of industry.

The South's first "large-scale dam" built to produce hydroelectric power was the North Highlands Dam, built by a consortium 2.5 miles north of Columbus in 1899. A second Chattahoochee hydroelectric dam was erected at Goat Rock in the falls north of Columbus. On December 19, 1912, special trains brought over 1,000 Columbus residents to witness the dedication of the new power plant. With the throwing of a switch, electricity surged down the power lines that stretched out to the north to LaGrange and West Point and eventually to Atlanta.

The advent of long-distance electrical transmission forever changed the way industrialists viewed the river. The Chattahoochee had once served only those towns located along its banks, but now the river provided power and lighting to people who could not even see the Chattahoochee from their homes. New mills in West Point, Newnan, and LaGrange took advantage of the power produced by hydroelectric dams.

The Bartlett's Ferry Dam of 1924 became the northernmost dam in the rapids of the Chattahoochee. Built 4 miles upstream from Goat Rock, its storage reservoir, known as Lake Harding, covered almost 6,000 acres and insured that the downstream dams had a constant flow of water for power generation.

These power generation structures added to the degradation of the Chattahoochee's navigability just as the First World War caused federal government officials to appreciate the importance of rivers to national security. The Army Corps of Engineers, President Woodrow Wilson, and Congress believed building an intercoastal waterway system to connect all Gulf of Mexico rivers by a protected saltwater channel along the coast was vital to national security. The federal officials authorized a survey of the Chattahoochee to consider improving the channel all the way to Atlanta by a series of locks and dams. The eventual report by the district engineer was not encouraging, but civic leaders along the river system took up the mantle of river improvement and flood control, and they labored for decades to lure "progress" into the valley.

West Point had more to gain from flood control than any other river town. In 1886 the river had slithered into West Point like a stealthy, red serpent. As the waters covered downtown streets, the steamer Charlie Jones circled the block. The covered bridge that spanned the river "rolled down the river like a log." Other floods followed in 1901, 1912, 1915, and 1918. The people of West Point learned to coexist with the river's quirky nature. They raised their wooden sidewalks to 5 feet above street level so they were less inconvenienced during the periodic inundations. But the worst flood of all tumbled down the valley in 1919. The Atlanta Journal detailed the destruction it caused: "The town of West Point is all but bankrupt. Until last Tuesday night there was no fairer or more prosperous community in Georgia. Clustered in the lap of the Chattahoochee River . . . it was rich in possessions and rich in resources. Its mills were humming, its merchants were preparing for a record Christmas season, its farmers were holding their cotton for higher prices, its homes were as cheerful as any you could find in Dixie, its 5,000 people happy.

"Then the yellow Chattahoochee, swollen with the heaviest rainfall in its history, burst from its banks, swept through the streets of the city, rose above the high sidewalks, rose above the high foundations of the buildings, rose above the stocks of goods on the shelves, rose above the pianos and sideboards and beds, rose until West Point was only one vast lake of mud and water."

Although West Point residents were the hardest hit, downstream residents were

not spared. In

Columbus the deluge was referred to as "the Pershing Flood" because it coincided

with the visit of General "Black Jack" Pershing to Fort Benning. Three years

later, the general was again at the post when another deluge was dubbed "the

Second Pershing Flood." Commenting on the frequency of the rises in the river,

the general said, "I thought all along Columbus would make a good Army post,

but I'm beginning to think it could also be used by the Navy."

Coping with the river's extremes became a way of life in West Point. A siren was installed to warn folks that the river had left its banks. A river gauge was placed under a floodlight at Smith Lanier's telephone building on the riverbank. It became the custom for men to keep vigil there when high water threatened, as if by their will alone they could hold the waters back.

In

1953 congress authorized the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint Project, which

set out to construct four dams on the Chattahoochee to address issues of flood

control, hydroelectric power generation, and navigation. The four dams were

scattered along the river beginning with the southernmost one, the Jim Woodruff

Dam, at Chattahoochee, Florida where the waters of the Chattahoochee and Flint

rivers converged. This undertaking named for James W. Woodruff Sr., who had

worked for decades for river improvement, included a dam for electrical power

generation and a lock to allow boaters to pass upstream. Water dammed behind

this structure would be known as Lake Seminole. Fifty miles north of the Jim

Woodruff Dam, a second lock and dam were planned at Columbia, Alabama. The reservoir

behind this George W. Andrews Dam would not widen so much as deepen the Chattahoochee

so that a 9-foot navigational depth could be maintained for the next 26 river

miles.

In

1953 congress authorized the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint Project, which

set out to construct four dams on the Chattahoochee to address issues of flood

control, hydroelectric power generation, and navigation. The four dams were

scattered along the river beginning with the southernmost one, the Jim Woodruff

Dam, at Chattahoochee, Florida where the waters of the Chattahoochee and Flint

rivers converged. This undertaking named for James W. Woodruff Sr., who had

worked for decades for river improvement, included a dam for electrical power

generation and a lock to allow boaters to pass upstream. Water dammed behind

this structure would be known as Lake Seminole. Fifty miles north of the Jim

Woodruff Dam, a second lock and dam were planned at Columbia, Alabama. The reservoir

behind this George W. Andrews Dam would not widen so much as deepen the Chattahoochee

so that a 9-foot navigational depth could be maintained for the next 26 river

miles.

Eighty miles north of the Jim Woodruff Dam, planners sketched out the Walter F. George Lock and Dam near the Fort Gaines, Georgia, and Eufaula, Alabama, area. This structure became the largest producer of electricity on the river, and its 45,200,000-acre reservoir became a fishing mecca. At the opposite end of the Chattahoochee, approximately 350 river miles from the Jim Woodruff Dam and 50 miles north of Atlanta, the Buford Dam was designed to regulate streamflow of the entire system so that a controlling depth of 9 feet could be maintained from the Gulf to Columbus. The lake behind this northernmost dam was named Lake Sidney Lanier after the renowned poet of the Victorian era who wrote The Song of the Chattahoochee. All four of these dams were completed by 1963, and Georgia Power Company built a final hydroelectric dam near Columbus known as Oliver Dam in 1959.

Beyond the Georgia Power dams at Columbus and the rocks and white water that forbade navigation between Columbus and West Point, Georgia's capital city refused to be excluded from the high-stakes game of post-World War II prosperity. As one Atlantan put it, a longer delay in developing navigation above the fall line would "imperil our entire commercial and industrial structure." Boosters easily saw that their best hope lay in joining forces with West Point in pushing for a dam that would save the latter town from another devastating flood because this dam could have the secondary purpose of backing up the water sufficiently to Atlanta to deepen the river for barges.

Mother Nature added her voice to the persuasive powers of the West Point Dam advocates. Early in 1961 almost 6 inches of rain fell on Atlanta in a 24-hour period. As the waters rushed downstream they washed out eight bridges in Troup County alone. Twenty others were damaged. Columbus, West Point, and neighboring towns were declared disaster areas. The dam's promoters took advantage of the emergency to request immediate funding, and in 1962 Congress finally authorized the West Point Dam (although it was not completed until 1975).

The northernmost dam envisioned for the Chattahoochee River was Buford. Like the others downstream of it, Buford was created for hydroelectric generation, flood control, and navigation. Perhaps its most important function was to provide a more dependable source of drinking water for Atlanta's explosive post-world war growth. After acquiring over 58,000 acres of rolling farmland, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began clearing a circular swath of land for the shoreline in 1950. The farms and houses inside that circle remained standing when the rushing waters of the Chattahoochee and its sister, the Chestatee, covered them seven years later. Poking out above the new lake's surface was a cluster of four mountaintops. These islands were developed by the state of Georgia into a popular resort now in private hands.

Today more than 60 recreational areas rim Lake Lanier. These include everything from a water park to a championship golf course, but also include marinas, campgrounds, and parks. It is one of the most popular man-made lakes in the country welcoming approximately 16 million visitors each year to its 38,000 acres. Twenty-three thousand boats ply these waters yearly. Ten thousand houses dot the shoreline. Most of these structures are the pricey second homes of Atlantans who overrun the lake each weekend.

The Atlantans who had hoped the dam's completion would be only the first step in connecting them by water to the Gulf of Mexico were gradually disappointed. The immense cost of the Vietnam War, which ended in 1972, as well as an international fuel crisis, fed a virulent strain of inflation throughout the 1970s. That condition, coupled with a postwar recession, sucked the vibrancy out of the American economy. No longer would discretionary funds be used to conform the physical landscape to man's economic ambition.

Instead of valuing the Chattahoochee River as a transportation artery, today's Atlantans see the river as a source of drinking water and the key to future growth. The states of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida all claim the river as their own and insist on their rights to use the river unimpeded. While bureaucrats squabble over water rights, the river flows quietly to the sea, a forgotten highway that remains the valley's most important asset.

Lynn Willoughby is a former professor of history and is presently a freelance writer. She has written two books about the Chattahoochee River. Her most recent work is Flowing Through Time: The History of the Lower Chattahoochee River.

Read and add comments about this page

Go back to previous page. Go to Chattahoochee River contents page. Go to Sherpa Guides home.

[ Previous Topic | Next Topic ]